RIA BHANDARKAR – DECEMBER 1, 2021

EDITOR: ATMAN MOHANTY

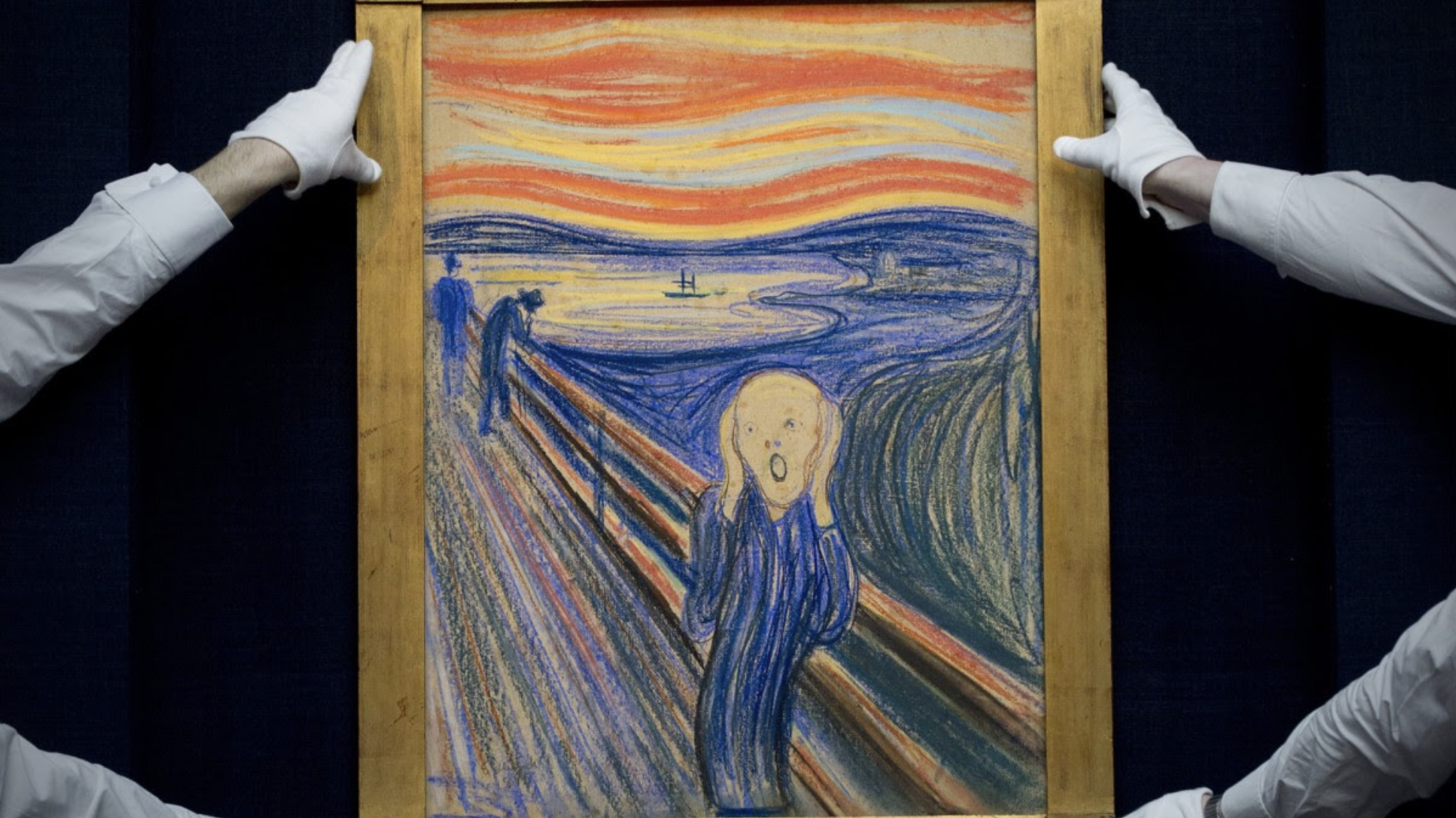

Edward Munch’s The Scream is one of the most recognizable paintings of all time. Its subject, a ghost-like figure gasping with its hands on its head, is memorable enough to be referenced in countless movies, art works, and even Halloween costumes. It also has one of the most troubled exhibit histories in recent memory. The original version of the painting was stolen from Norway’s National Gallery in 1994 and another version was taken from the Munch Museum a decade later. After the second theft, a museum was scheduled to be built in dedication to Munch, but it wasn’t until 2021 that it opened in Norway. The two stolen pieces, now recovered, sit in the new exhibit.

The Scream and similarly revered works are iconic and highly valuable. But why would anyone want to steal them? It’s easier to understand a market for stolen laptops or cars, which are affordable for enough people and not easily traceable. But if a thief got their hands on The Starry Night by Vincent Van Gogh, who would be willing to pay millions of dollars for it? And if they could secure a buyer, where would they keep such an obviously stolen item?

Criminals tend to be good at stealing and bad at selling. According to Robert Whittman, a former undercover FBI agent, it’s rare to see a real-life Bond villain who will pay to have their own Monet. In fact, many thieves hit a wall once they actually get a Matisse or a Picasso or a Rembrandt. So why steal art? Although art theft may seem irrational, and the value of artwork is difficult to quantify, it is possible to model the behavior of actors who decide to steal art and create the best solutions for museums that wish to deter heists.

Inside the Mind of an Art Thief

The popular media narrative is that art thieves must be short-sighted, since it can be difficult to make a profit once they have stolen a piece. It is easier to think that thieves are looking for some form of glory and are just willing to risk anything to get it, even if the chances of succeeding are small.

However, criminals’ motivations to steal art can be more complex and are highly dependent on what they are able to steal. They need to have some sort of motivation that outweighs the consequences. In the paper “Motives of Art Theft: A Social Contextual Perspective of Value,” Dr. Marion Johnson Wylly argues that there is a direct correlation between the financial value of art and a thief’s incentive to steal it. Since heists can take a lot of time and resources, a thief may make decisions like any producer: maximize the revenue they make from selling the painting while keeping in mind the cost it takes to procure it.

One confusing aspect of an art thief’s decision calculus is that the value of art is highly subjective and not always clear. While it can be easy to figure out the approximate price to sell a stolen car, the value of art can be divided into artistic, political, and financial components. The latter part is easy enough to understand but the first two can create complications. While some art thieves are part of general organized crime organizations, many specialize in art theft so they can understand the industry value of each piece.

Some art thieves care less about the money and more about the political value of a piece. For example, Mullah Omar, the founder of the Taliban, encouraged the theft and destruction of Bamiyan statues which portrayed Buddha and dated back to 570 AD. To him, the financial value mattered less than what the statues represented. Meanwhile, a Polish construction worker stole a Monet painting for the purpose of admiring it, indicating that the artistic value of a work can be enough of a motivation.

Whatever the motivations people have to steal art, the consequences are the same for the museum. Many pieces are never recovered, and ones that are can be too damaged. The majority of thieves steal with an intent to make a profit. To really understand the decision making of an art thief, it is necessary to understand how they make that profit.

Selling What You Stole

Once a thief has successfully stolen a valuable piece of art, they may hit a wall when they try to sell it. Since most art crimes can be as simple as walking up to a painting and grabbing it, not every thief thinks too far ahead. There aren’t too many people who would risk buying a stolen art piece so many desperate art thieves will end up putting a ransom on the item, which is usually reported to the police.

However, there are rare cases where a stolen item can be turned into something else. For example, in 2017, a 100 kg gold coin was stolen from the Berlin Bode Museum. Although suspects in the case were arrested, the coin itself was never found. Later, investigators noticed gold dust in the suspects’ car. That observation helped them conclude that the coin must’ve been melted down and sold. While it may be hard to find someone to buy a stolen Monet, there is a market for gold and these thieves had over 200 lbs. worth.

Unlike the gold market, art buyers worry about things like legal titles when they buy paintings. The best chance a thief has is to go for quantity over quality. Instead of grabbing a piece worth millions, some lesser-known ones valued in the thousands can be sold much more easily at flea markets or secondary art markets. Otherwise, the only value a thief would get from their heist is a reputation.

Selling stolen, less well-known, paintings is more common than expected. Gregory Day describes the art market as secretive, a reality which creates many inefficiencies. Since many collectors don’t want to publicize their sales and invite interest from thieves, they use intermediaries for sales who have less information about their pieces’ histories. Buying a stolen painting could lead to a lawsuit or, at the very least, being forced to return a painting without compensation. As a result, reputable dealers often sell works with warranties for authenticity and title to convince buyers that they are not purchasing stolen art. However, there are plenty of more informal transactions that don’t include warranties. Theft in the art industry increases secrecy, which in turn creates more instances of information asymmetry.

The Security Paradox

As an institution displaying valuable artwork, a museum must have at least some security measures in place. But while many would expect a museum with the most illustrious collection to spend the most on security, higher security measures signal a higher value, which makes them more tempting for potential thieves. A museum has to consider many different factors, including resources in law enforcement, to decide how to invest in security.

Italian economists Antonio Nicita and Matteo Rizzolli have modeled the effect that investing in security measures for a piece over increasing the piece’s publicity can have on a thief’s profits. The “resaleability” of a painting is defined as the difference between its black market price (pbm) and its hypothetical market price (pm). For a famous painting like Starry Night, its fame would lead to the pbm being lower than the pm since it would be too easy to detect that it’s stolen. At the same time, a run-of-the-mill painting would also have a low pbm since there wouldn’t be anything special about it and it wouldn’t make sense for a thief to put in the effort to steal it.

Nicita and Rizzolli explain that an owner’s investment in precautions increases the thief’s expected pbm since it seems more valuable, although it also makes the thief’s cost to steal it higher. Instead, the owner could invest in the artwork’s publicity, public knowledge, and advertisement to make the thief’s profits smaller and create their own Starry Night situation. Owners must navigate the trade-off between spending more on fame and spending more on security.

Other economists have studied this game-theoretic model in which owner’s invest in protecting their collections, thieves invest in their heists, and law enforcement decides on methods to recover stolen works. Different policies can have major shifts on the economic models created by Nicita and Rizzolli. For example, a policy that creates more resources for law enforcement can actually increase the amount of theft in equilibrium since museums will spend less on security. Meanwhile, policies that increased penalties for theft could be more effective in increasing museum security.

Conclusion

To the average person, stealing art may seem like a high risk, low reward endeavor. A heist can be expensive and difficult to pull off and a painting without a legal title isn’t easy to sell either. However, the decision making of an art thief is more complex than just a non-risk averse actor taking a chance. There are plenty of ways to determine a piece’s value, and at least one is usually enough of a motivation to steal a painting. And while the term “art heist” brings to mind a team of thieves stealing a Rembrandt, in reality there are plenty of lesser known works which can be sold on the black market.

Art heists are a great example of information asymmetry. The amount of security around an exhibition can signal the value of its works—this is especially important since the value of art is highly subjective. Similarly, the existence of stolen works in the art market is a result of the high level of secrecy unique to that industry, which prevents full transparency around each purchase.

There are many complicated obstacles and incentives around art theft and the purchase of stolen art but economic models, such as the ones created by Nicita and Rizzolli, are able to show how museums and thieves make trade-offs. However, these models, like any, are reliant on several assumptions, mainly that financial incentives are the driver behind most heists. There are still plenty of other reasons that thieves may value art, though those are more difficult to quantify.

So when a thief walks up to and steals a Rembrandt, what happens next? The painting may be sold on the black market for a respectable sum. It could be in an underground safe, with no chance of being sold. Or maybe it’s hanging in the thief’s own home, to be admired whenever they wish. Maybe money can’t explain everything.

Featured Image Source: history.com

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.