KONNOR VON EMSTER – OCTOBER 30TH 2020

EDITORS: KAT XIE, KAREENA HARGUNANI

The 2016 election was a shock to many. In liberal parts of the country such as my own locale in the heart of Silicon Valley, few believed that Donald Trump had any serious chance of winning the election. Trump’s radical redefinition of the political landscape seemed bizarre and unlikely to win a role traditionally held by outwardly moderate individuals.

Alas, it was precisely Trump’s populist and reactionary qualities that led to his victory in 2016 (and potential re-election next week). This populist trend was reflected around the world in the referendum that led to Brexit (only now is it close to completion) and the election of multiple right-wing conservatives in 2016. Trump promised monumental yet often vague change: to take down the mainstream media, to “drain the swamp” of Washington, and, by far the most popular, to “Make America Great Again.” Because of his presumed business acuity and status as a government outsider, many believed that he could deliver on these promises.

Trump’s promise to Make America Great Again (MAGA) was his leading slogan in 2016, and its impact was profound. Many Americans, upset with the state of the world, were captivated by this promise. Going back in time meant returning to their jobs, enjoying a stratified and ordered society, and reclaiming their dignity and respect. Trump campaigned heavily in states that had seen significant numbers of manufacturing jobs shipped overseas and rustbelt states that had experienced monumental strife after coal mines and factories were shut down. Many liberals wrote off Trump’s promises as impossible but Trump gave hope that the middle-class, blue-collar lifestyle would return. Of course, Trump has been largely powerless to make the global changes needed to fulfill this promise, but his message stood: he wanted to restore American greatness.

Trump did not provide many specifics but many Americans expressed their desire to go back to particular periods when America was great. The 1950s and 1960s often stand out in people’s minds and have been described as the “Golden Age of American Capitalism.” Blue-collar jobs were plentiful, well-paid, and respected; the middle class was huge; inequality was low; and the US economy was growing at breakneck speed. Trump sought to capture this nostalgia in his promises to bring back blue collar jobs but he has largely avoided the policies that once brought American greatness. Why? Because what separates this era in US history is surprising to many: it was largely socialist in spirit.

MAGA’s Power

MAGA sums up Trump’s 2016 victory succinctly. Whereas Hillary Clinton won the popular vote through resounding victories in democratic strongholds, Trump won the electoral college through narrow victories in Midwest and Rust Belt states. Every battle-ground state Trump won had been suffering financially as industry eroded during economic expansions and recessions. Clinton was a progressive, Trump a reactionary. The “again” of the slogan spoke to his and many Americans’ desires to reclaim many facets of American life. Trump reversed almost every Obama era policy right after entering office.

Make America Great Again has been described by some as perhaps “the most powerful and memorable political slogan ever.” And it is easy to see why. Years after the 2016 campaign, Trump is still touting its power. The classic red baseball cap adorned with the slogan has the power to divide a room. Its simplicity is astounding but important; it would not be memorable or compelling with any other wording. Everyone wants to be great. But as others have pointed out, it’s the word “again” that wields the most power. What unites most Trump supporters is the sense that they benefit by going back in time. Many, like the steel mill workers in Fairfield, Alabama, feel that the world does not need their talents anymore. Their prime has passed, and they linger on hope.

Of course, hope came to the aid of former President Barack Obama as his motto in 2008. Shocking to many liberals is that many Trump voters also voted for Obama. Obama campaigned broadly on economic success and stability for the average American. He let down many Americans’ economic hopes in the long wake of the Financial Crisis. Hillary was perceived as an extension of Obama’s inaction whereas Trump was a possibility for something new and a guaranteed shake-up of mainstream politics.

Trump appealed to disenfranchised people upset with empty liberal promises. His radical promises of a broad return to post-war economic greatness included breaking the deadlock in Washington over working class stimulus. Clinton represented tradition more than ever and Trump leveraged this throughout his campaign. Trump offered hope to the disenfranchised and economically challenged. It only became clear to the public how many lingered on Trump’s promises after his election in 2016.

Trump was able to win over white working class voters who had lost their economic footing in the preceding decades. White voters with no college degree swung over 15 points more Republican than in previous elections. This Harvard Business Review article unpacks why many middle class workers deplore elitism but not wealth. Many men are deeply uncomfortable with the idea of working service jobs in what is considered “feminine” work. Many dislike the different societal norms and political correctness embraced by the professional class. Trump’s straightforwardness and lavish lifestyle represented their ideal way of life. And yet most infuriating for the working class is the disdain and mockery coming from the professional class. To them, Hillary’s use of the word “deplorables” to describe fellow Americans was blasphemous and turned off many potential voters. Many Americans feel humiliated by liberal offers of welfare and professional services when what they desire instead is their former jobs. They want back their dignity, and Trump’s cultural promise of reinvigorating the respectability of blue collar work is too promising to pass up.

Yet, institutionally, people were (and continue to be) driven toward service work. Coal mines and steel mills have been driven out of the US through globalization and trade agreements. While it is hard for companies to pass up cheap steel prices, Joan C. Williams reminds many that job retraining and location programs must be considered an additional expense of such trade agreements. Unlike job retraining programs in other countries, options in the US are limited and underfunded. In an NPR interview with steel workers who lost their jobs, several couldn’t afford to stay in the job retraining programs. Many used to be union workers that then decided to vote Republican because of Trump. Several lacked skills such as computer savviness and software proficiency that many recruiters deem necessary nowadays but were not needed in the steel mill. Unbeknownst to many, this silent sect seemed to have swung against polls in the states Clinton needed to win the most: Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania.

While the message of MAGA was powerful, it begs the question, what era does MAGA apply to? When was America so great?

The Golden Age of American Capitalism – 1950s and 1960s

Despite the chronistic ambiguity of MAGA, it is possible to imagine an era that the values of MAGA applied to the most. The NYTimes Morning Consult surveyed a diverse sample of 2000 people on their general feelings on the country throughout different decades and compiled this data to answer the question, “When Was America Greatest?” The results were largely skewed to the 1950s and 1960s for those born before that time, and toward the 1980s for those born after.

What made those decades so great? Scholars often reference the Golden Age of American Capitalism whereas everyday Americans frequently reference more qualitative socioeconomic aspects—respect, prosperity, a strong middle class, and a structured family life. Of course this era was not without strife and contained events such as the Vietnam War, Civil Rights movement, and other social injustices.

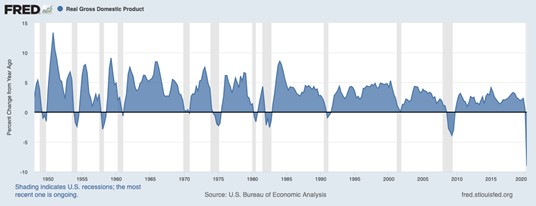

Scholars define the Golden Age of American Capitalism as the period between 1950 and 1970 that saw a substantial rise in real income, growing at an average rate of 4.4% per year. For comparison, the average rate of real income growth from 2000 to 2020 was a mere 2.1%. Many Americans entered the middle class and had the chance of pursuing the American Dream to hold a steady job, own a house, raise a family, and afford the occasional vacation.

Blue collar labor was more common and well-respected then. Though blue collar labor is often mislabeled as unskilled, it is more accurately defined as skilled, often laborious work that does not require a college degree. Typical blue collar labor includes construction, mining, technician work, and craftsmen trades that require certain skills that are not easily transferable to technological jobs.

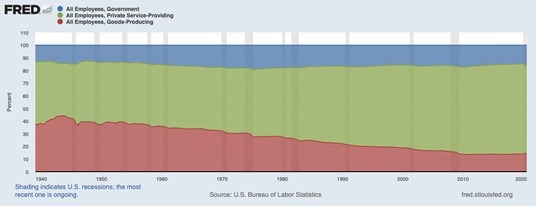

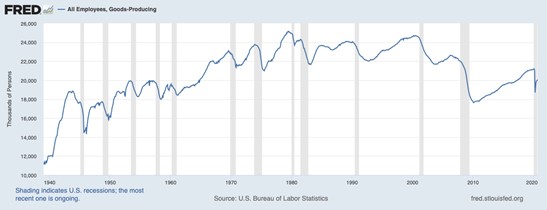

Blue collar work that had once been unviable for a family lifestyle became sustainable throughout the 1950s and 60s. Manufacturing jobs allowed for a middle class income. Productivity abounded for such manufacturing. Mild business cycles meant more sustained income and greater satisfaction among laborers. Some contribute the sparingly few and shallow recessions to the amount of goods manufacturing at the time which is in stark contrast to the service heavy economy of late. As indicated by data from the St. Louis Federal Reserve Economic Database (FRED), goods producing (often blue collar) labor represented around 40% of all workers. Since the Golden Age, goods producing workers have shrunk to 40% of what it once was, or around 16% of employed workers, with the service sector expanding greatly.

Most disheartening is that once blue-collar jobs are gone they seldom return. In almost every recession, thousands of goods producing jobs are lost. If workers are lucky enough to be hired back, they still must live on unemployment or find other work in the meantime. For most of the men involved (a vast majority of blue collar workers are men), their job is their livelihood and a part of their identity. The 1950s and 60s was a time when their identity could be shown proudly and was well respected. But now, many fear losing their jobs and subsequently, part of their masculine identity.

The steady decline of blue collar labor was caused by two major factors: automation and globalization. Workers are very costly; they often require benefits, wage increases, safety training, etc. Replacing American workers with machines and overseas labor presented many companies with higher upfront costs but lower marginal costs. One by one, many factories opted for these changes, leading to the steady decline in blue collar work.

The Golden Age of Capitalism was also known for its remarkably strong middle class and low inequality. The median income could support a family and provide a few luxuries whereas now it is difficult to support a family on the median income, let alone pay for extraneous purchases. Many have reported on the shrinking middle class (Pew, Fortune, NYTimes, and Fox to name a few) because its disappearance is important to many. Since the prime of the middle class in the 1950s and 60s, money and class have divided America further and caused hardship for many. It is no wonder that people want to return to a society with a strong middle class.

It should be no surprise that the shrinking of the middle class was most difficult for those with just a high school diploma. Their group shifted most into the lower income sector between 1971 and 2015 as reported by FiveThirtyEight. While income has expanded in professional industries, there has been little real change in middle class income, with yet more people falling into the lowest class of income.

While data on Gini Coefficients, the traditional metric of inequality, is sparse for periods before 1980, the US Gini Coefficient has been on the rise since 1980. US inequality has risen from 35 (about the same as the UK and Canada) to 45 (around the same as Russia, Mexico, and Brazil). Many have studied trends in wealth and income since the 1980s. Middle income and wealth has decreased while upper income continues its accelerated rise.

Innovation was central to US success and the world respected the US because of it. When Americans landed on the moon, people saw it as a worldly accomplishment. America had shown its prowess to innovate and it gave the American people something to be proud of. America reaped many of its technical innovations developed during the war during this period including long distance phone lines, radio communication, microwaves, and television, all of which contributed to the rise in the standard of living.

Due to all of these qualities, it can be easy to understand why many would benefit from returning to the 1950s and 60s. Yet it would be a mistake not to mention the various people that struggled and died during this era, namely African Americans. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 signaled a change but it was achieved after many lives were already lost. Indeed, the legacy of slavery lives on through America’s enduring caste system which may explain the continued economic struggles of African American communities throughout the US. Interesting still is the fact that segregation was further developed after the Civil War and blacks and whites lived more closely together in the late 1800s than they did in the mid-1900s. Many groups have gained from the advancements of modern society including women and LGBT+ groups. Some, like the governor of New York, Andrew Cuomo, truly believe, “America was never that great,” and that our best days are ahead of us.

When asked the question of “When was America great?” Trump often brushed it aside (potentially to keep its chronistic ambiguity alive) except in a Times interview in March of 2016. He stamps the greatest era as the turn of the century with Truman and Eisenhower saying, “the late ‘40s and ‘50s … we were not pushed around, we were respected by everybody, we had just won a war, we were pretty much doing what we had to do, yeah around that period.” The man behind MAGA agrees that the greatness of America was during the era of post-war reconstruction and the Golden Age of Capitalism.

The Great Twist

But what distinguished the 1950s and 60s from all other boom times before and after that era? And why did the boom uniquely benefit the blue collar workers in the middle class? Each of the measures listed above and yet more made the 1950s and 60s great. While this greatness had many causes, one of the foremost was government involvement. To the great surprise of many, numerous features of the post-war economic expansion can be attributed to policies that were more socialist in nature.

Let’s look at one of the most defining features of the 1950s and 60s: the exceptionally strong middle class. It was no fluke, and was deliberately maintained through strong labor protections, government welfare spending, and, most notably, taxation of the rich.

These policies contributed heavily to the aforementioned lower inequality of the time for the rich were bound from becoming ostentatiously wealthy through taxation and the lower and middle classes were supported through government programs and labor protections. Middle class workers were further protected through regular wage increases won by union negotiations. Low inequality fosters national unity, while high inequality tends to sow division along financial lines.

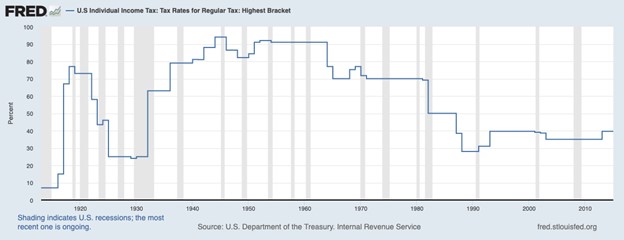

A shocking fact for many is that the highest marginal income tax rate was 91% in the 1950s and the effective average tax rate hovered around 50%. (For those who need a refresher on marginal tax rates, check out this article.) This was decreased to 70% in the 1960s but remains in stark contrast to the highest income tax rate of today: 37% (although the top 1% pay only 26.8% income tax on average). The median income earner in 1960 received $5,600 in income and paid a tax rate of around 22%. In contrast, the median earner today pays about 10.8% in taxes.

Many likely believe that the stupendously high marginal income tax rate of the 1950s and 60s was an example of broad government overreach, but it only captured income over $1.5 million per year in inflation-adjusted terms, an amount over 30 times that of the median salary. The income of that individual is more than many Americans could expect to make in a lifetime, which is why the high income taxes were broadly accepted at the time. These high tax rates reigned in inequality and largely kept Americans from separating themselves into socioeconomic classes.

Corporate taxation was high as well. Back in the 1950s and 60s, the maximum tax rates hovered around 50%, a far cry from 21% after the Tax Cut and Jobs Act of 2017. These policies reined in corporate earnings and encouraged companies to reinvest in their employees and technology, driving future growth.

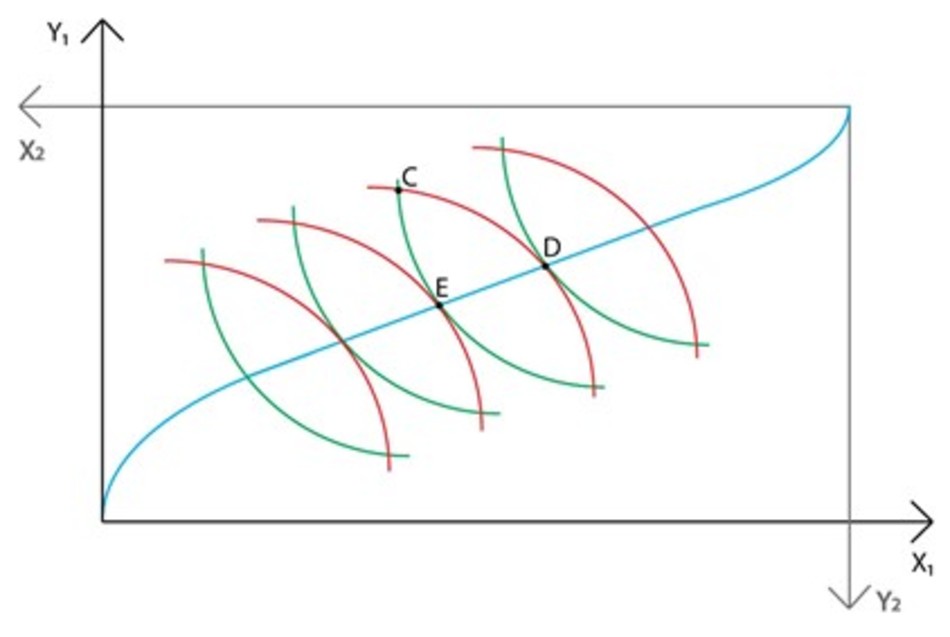

Many critics today argue that taxes on high income earners and corporations come at the expense of real growth. This was certainly not the case in the 1950s and 60s and there is scant evidence that high income taxes would stunt growth today. Studies have shown that high levels of inequality actually hinder growth, explaining why the high tax rate that maintained equality actually accelerated growth in post-war America (and may provide a partial reason for the current sub-par growth rate). The theory rests on the fact that middle class Americans spend (rather than save) a larger proportion of their income than higher class Americans. That is to say their marginal propensity to consume is greater. Most introductory economics courses discuss the multiplier, an idea that the more money is spent, the more output and thus income there is in the entire economy (domestic output equals domestic income). High income inequality leads to more income in the hands of more wealthy people, who are less likely to spend it. This is the basic logic of why trickle down economics fails to create middle class jobs and why the reverse is actually needed for long-term, sustained growth.

Consider too that government taxation can be an impetus for innovation, fueling long run growth. In macroeconomic theory, A, or aggregate knowledge, describes increases in productivity specifically through technology and research and development. The large government receivables allowed for huge investment in government laboratories that funded research and development and drove the rapid increase in aggregate knowledge. Increased technology and knowledge spurred increases in efficiency which fostered increased productivity for workers. Because of strong labor unions and high tax rates on corporations and high income earners, the income generated by these productivity increases was broadly shared among business owners and their workers. Because labor unions were strong, they were able to negotiate wage increases that allowed workers to reap the benefits of the technology they were using which ensured more equitable distribution of income throughout corporations. Today, it is largely the shareholders and business owners that reap any benefits borne from increased productivity.

Labor unions were indispensible for the regular wage increases that allowed blue collar labor to maintain its middle class status throughout the 1950s and 60s. Data shows that union membership grew throughout the 1950s and 60s before reaching its peak in the 70s. During this time, unions lobbied for regular wage increases to keep up with inflation and maintain members’ standard of living. Unions organized strikes to gain benefits and many workers participated in them. Unions allowed blue collar workers to assemble and wield political power to maintain their middle class status. When technological innovation threatened workers, unions negotiated to benefit from the increased productivity while reassigning those workers onto new jobs. While imperfect, they offered an important backstop against blue collar workers slipping into lower echelons of society.

Government funded programs including the space race, government labs, the interstate highway network, and interstate telecommunication expanded science and, by extension, the economic knowledge coefficient, all of which pay dividends to this day. The vast network of the Department of Energy National Laboratories (DoE National Labs) that developed the atomic bomb contributed greatly to our understanding of physics and technology. The government funded nearly 70% of basic research in the 1960s and 1970s by continuing to hire physicists and engineers after the war. Born in these labs were early computers and the early internet (although success has a thousand fathers and it is hard to truly decipher where it began). Most of the basic technology used in our cell phones was developed in these labs. Many of the products contributing to American superiority (including the innovations of Silicon Valley) can be attributed to these national labs.

Unfortunately, the research and development industry continues to be privatized, which has eroded America’s reign as innovative champion. Not only has the privatization made operations less efficient than before, it has failed to produce the innovative discoveries needed to keep America on the leading edge. Many have commented on this decline, including some of America’s biggest producers of basic research and aggregate knowledge: universities. The President of MIT, L. Rafael Reif, describes this beautifully in his Op-Ed: “The Dividends of Funding Basic Science.” This appeal for increased research funding describes the monumental impact that basic science, founded at most universities and national labs, has on the world. It has been proven too that the DoE National Labs produce innovation at a cheaper cost than private companies, and could excel further with restructured management.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding for basic research has also slipped year over year in inflation adjusted terms and is poised to erode the leadership of US healthcare innovation. The effects of reduced basic technology R&D spending over the last 30 years have begun to coalesce in the US trailing the Chinese government in telecommunications technology, namely 5G. If the NIH funding is not increased the US may lose one of its biggest exports: scientific licenses.

The 1960s also saw enhancement of the American welfare system created in the 1930s by Franklin Delano Roosevelt. In 1935, the Social Security Act was passed in order to save retirees from poverty and provide them insurance against retirement misfortune. Then, in 1965, Lyndon B. Johnson signed legislation to begin Medicare and Medicaid. These social programs are now used by millions of Americans, and continue to be broadly supported. While they did not extend health insurance to the general public at that time, the US joined a wave of countries approving forms of universal healthcare during the 1950s and 60s. Socialized healthcare was one of the final hallmarks of the era of post-war greatness. Paradoxically, many voters receiving socialized medicine (namely older retirees on Medicare) are the ones supporting Trump in blocking its adoption by the general public.

Conclusion

Has Trump ever said we should go back to socialism? Absolutely not. But if he wants to uphold his promise to the American people, he might have been more successful if he were to lobby for higher taxes, stronger worker protections, and the same strong safety net that was available to people in the 1950s and 60s. In order to truly Make America Great Again, people might consider voting to Make America Socialist Again.

In fact, MAGA has been criticised by others for its contradictory message and its lack of historical grounding. Others too have interpretations on how we might expand the middle-class. Many have criticized his reactionary approach but few have dove into the importance of his message for many Americans and its historical interpretation.

Many may then ask: if Trump wants to bring us back to the greatness of the 50s and 60s, why is he so against the socialist policies that contributed to our past success? A definitive answer is impossible but hypotheses include support of the mainstream Republican platform (that is antithetical to the post-war expansion) and personal gain.

Instead of considering the past policies that may have contributed to past economic greatness, Trump has reinforced the idea that liberalism is contributing to the destruction of the economy. His message is a restatement of Republicans before him, suggesting he is not so different from them. Trump’s hypocrisy includes criticizing Obama on many actions that he later embraced and extended such as using executive orders and golfing. Trump’s promises have only partially succeeded or been entirely abandoned, although that has yet to disappoint many of his supporters.

One of his biggest failures was one of his supporters’ most fervent topics: draining the swamp. For a man who bashed mainstream Republicanism and promised to clear out the Republican congress, he is certainly friendly with all its members.

Trump stood to gain from corporate and personal tax breaks. Since 2016, Trump’s presumed business acuity has been debunked in a series of NYTimes articles studying his tax returns. In order to facilitate his vast wealth further, he needed tax breaks and more attention to drive business to his vast chain of property holdings.

What could be more favorable PR for Trump’s brand than his election as President? We now know that most of Trump’s wealth was amassed through the TV show The Apprentice. Most of his further wealth was accrued by licensing out his name. Trump had run for election several times before 2016 on a more moderate platform before finally finding a heartstring in the MAGA promise.

The past four years have been Trump’s opportunity to restore policies that helped the middle class, drive innovation, and restore honor to the American people. He has instead driven us further from that path and ridiculed the scientific and economic bills aimed at supporting America long into the future.

If one were to forget about President Trump for a minute, would America be ready to go back to the policies present in the 1950s and 1960s? The policies described require societal cooperation and community, let alone a massive sacrifice for individual earners in the upper class of society. The America of today is far different and diverse from 1960.

A large sect of Americans seem to believe that we can return to socialism and are supporting democratic socialists such as Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren. Regardless, few truly understand that America does not need to reinvent the wagon wheel when it comes to socialism. In fact, we can re-instill tax policies that existed 60 years ago and regain the greatness and honor we once had. If Trump or any president truly wanted to Make America Great Again, they would first have to make America socialist again.

I would like to add special thanks to my editor, Kat Xie, my friend Daniel Malkary who made this happen, and also Professor Raymond J. Hawkins, whose Economics 100B lectures and comments inspired this article.

Featured Image Source: Penn State Read, Think, Share Discussion Blog

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.