HANNAH SHIOHARA-OCTOBER 25, 2022

EDITOR: DENYSE CHAN

The Parade

Imagine you are at a parade. Between 12 p.m. and 1 p.m., every single person in the economy will walk in a single file line arranged in order of income, with those earning the least at the front and those earning the most at the back. In this parade, marchers’ heights correspond to the amount they earn, such that people with an average income are of average height, while those making twice the average income are of twice the average height. As a spectator, let’s say you are of average height.

At 12:10 p.m, you check your watch, puzzled, as no one has yet to walk by. The parade had actually begun but the first several marchers cannot be seen; they are walking upside down with their heads underground. These are the people suffering from debt, many being owners of loss-making businesses. Slowly as time passes, upright marchers begin to pass by, but they are so tiny that spectators are peering down on them. Finally, at 12:45 p.m., the people walking by reach your height. These are the individuals earning the U.S. mean household income of $70,784 in 2021. The heights of the marchers start rising more quickly than before, and in the last 6 minutes, heights start skyrocketing. Doctors and lawyers that are 20 feet pass by, and by the next moment, successful corporate executives and bankers who are 50 feet, 100 feet, and 500 feet walk by. In the last seconds of the parade, pop stars and the most successful entrepreneurs pass by, but they are so tall you can only see their knees.

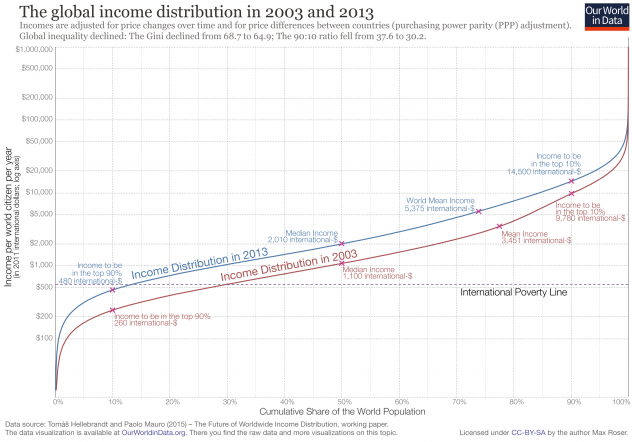

This parade is called the Pen’s Parade. It was introduced by Dutch economist Jan Pen in his revolutionary book Income Distribution in 1971. The parade is a visual illustration of the quantile income distribution graph, which places the cumulative share of the population on the x-axis and income on the y-axis. As seen in Figure 1, the rise of income earned (y-value) is relatively slow in the first four income quintiles, from 0-80% on the x-axis. This corresponds with the illustration given in the Pen’s Parade, as marchers’ heights rose very slowly from 12 p.m. to 12:45 p.m. However, the graph depicts incomes skyrocketing in the last income quintile, demonstrating that a small percentage of the population earns a significantly greater amount of income than everyone else in society. The less even the quantile function is, the greater the income inequality in a given society.

Image Source: Our World in Data

The Pen’s Parade Today

In 2021, global income inequality increased for the first time in 10 years due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The global health emergency caused a spike in economic inequality to levels last seen a decade ago, undoing several years of progress in reducing poverty.

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the world’s top 10 richest men have doubled their fortune from $700 billion to $1.5 trillion, while the income of 99% of humanity has decreased. For reference, Elon Musk, the last giant to walk the Pen’s Parade today, would be 10 times taller than last year, as his real wealth increased by 1016%. Furthermore, the top ten billionaires now own more wealth than the bottom 40% of the global population combined, suggesting that vertically stacking almost the entire first half of the parade’s participants would still not be enough to match the height of the last few men walking.

COVID-19 Exacerbates Disparity Between Main Street and Wall Street

As the pandemic drastically increased demand for online services and tech products, the CEOs and shareholders of technology companies such as Apple, Google, Amazon, and Facebook were the big winners; Amazon’s shares went up by 87% over the past 15 months, and Tesla’s stock is up by more than 700%. These winners were already some of the wealthiest people on the planet before the pandemic.

Moreover, though the stock market was temporarily shaken in March 2020, it has since rebounded and soared, leading to a large disconnect between Main Street and Wall Street. While life soured for those on Main Street, which represents the “real economy” with the average investors, small businesses, and investment institutions, stocks were doing better than ever before on Wall Street, which is made up of global corporations and high net worth investors. While food banks were overwhelmed with people experiencing food insecurity, the Dow Jones Industrial Average hit an all-time high.

The central bank announced several measures that would help support the economy and markets, acting as a catalyst for a swift stock market recovery. Expansionary monetary policy cut interest rates to a record low, and when rates couldn’t be pushed down any lower, quantitative easing was employed. Low bond yields also left investors with no better place to put their money. Unfortunately, the Federal Reserve has a significantly larger influence on Wall Street than Main Street, with a majority of its programs aimed at helping small and medium-sized businesses being less effective than those aimed to aid large corporations. The Main Street Lending Program, which was supposed to lend $600 billion to small and medium-sized businesses during the pandemic, has only assisted 1% of businesses that qualified, leaving the 50 million employed in this sector to suffer. Bharat Ramamurti, a part of the congressional oversight committee and one of the leading voices for this program, has stated that “so far it [the program] has failed.” Additionally, large corporations strongly believe in prioritizing their shareholders and maximizing profits. This meant companies focused on increasing share prices for a small portion of the elite, while putting a downwards pressure on all other costs, including wages for workers. These combined factors have exacerbated inequality in the American economy, disproportionately negatively affecting those on Main Street.

Implications of Inequality on Health Care and Education

Though income inequality is largely fueled by the events and decisions made in the corporate realm, its impacts can be felt throughout all aspects of society. Low-income communities continue to be under-resourced, increasing the gap in academic achievement and educational attainment between high-income and low-income children. Children in poverty are disproportionately disadvantaged when looking for labor opportunities, creating a poverty cycle that they do not have the resources to break out of.

Income inequality also drives healthcare inequality, with those living in poverty to be at higher risk of serious illness if infected with COVID-19. This is largely because low income populations have restricted access to proper healthcare, due to geographical location, asymmetrical information, and/or their inability to take time off of work. Poor health also results in reduced income, creating a health-poverty trap.

Why Income Inequality is So Hard to Resolve

Systemic issues such as income inequality cannot be resolved without structural reform because its cause cannot be attributed to one factor, rather, the issue is inherent within the overall system. In order for impactful and lasting change to be made, our society requires dialogue, compromise, and a consensus from its citizens. However, America continues to become increasingly politically polarized—at a rate faster than any other democracy. There are virtually no ideological overlaps between the Democratic and Republican parties, and the share of people with a negative view of the opposing party has more than doubled since 1994. The Attack on Capitol Hill of January 6th, 2022 symbolized this national divide, as supporters of former President Donald Trump descended into the U.S. Capitol and ransacked congressional offices.

Though it is difficult to identify the causality and direction of political polarization and income inequality, there is substantial evidence to conclude that the two phenomena are correlated. Income inequality is quantified by the earning gap between the highest and lowest income decile, and political polarization is calculated by subtracting the share of individuals identifying as extreme Republicans from those that identify as extreme Liberals. Analysis of data collected depicts that a 1 percent rise in income inequality is associated with a 0.18 percentage point increase in political polarization. Furthermore, higher levels of polarization are associated with lower labor productivity, with fewer hours worked and higher unemployment.

The increased income inequality thus suggests that the nation will only become even more polarized. People who received little support in times of crises will have vastly differing values and sentiments within politics compared to those that thrived during the pandemic. Even though our society needs solidarity to close the gap between the extremely wealthy and the poor, divisiveness continues to pervade.

Moving Forward

The increase in income inequality after the COVID-19 pandemic is a wake-up call for the urgent need for change. Though there is little common ground among Americans as to how income inequality should be addressed, there has been one common voice: the importance of education and skills training. While Democratic and Republican views on direct financial assistance and taxing the wealthy are split, about 80% of U.S. adults who believe that there is too much inequality agree that governments should invest in education and job training for the less skilled.

Education about inequality should start at a young age, such that our youth grow up understanding how systemic issues are formed and what their root causes are. For example, the Pen’s Parade is a great visual of income inequality to inform those that may be unfamiliar with the concept. Skills training and education for adults must be accessible and provide enough compensation to incentivize people to participate. Though this is easier said than done, closing the gap between the rich and the poor is necessary not only for the well-being of our citizens, but for the economy and society as a whole.

Imagine you are back at the Pen’s Parade. Only this time, you don’t have to wait 10 minutes to see the marchers, because they are no longer upside down. They attended skills training programs and now earn enough to get by. Though there is still some disparity in heights, you don’t find yourself peering down on some and straining your neck to look up at others. People have equal access to resources and opportunities to grow both professionally and personally. This is the parade our society should strive to host.

Featured Image Source: The Hill

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.