NELSON LAW – MAY 5, 2024

EDITOR: EMILY PHUONG VU

Economists are the logicians of humanity: experts who rationalize a world of complexity and chaos. The discipline revolves around ‘scarcity’: the use of resources, the production of goods and services, the growth of production and welfare over time, and other issues of vital concern to society.

Yet, these ‘logicians’ can’t seem to get it right, from Adam Smith’s invisible hand falsified by the Great Depression to the Keynesian school of thought disproven by stagflation. In fact, 2023 is a prime example of economists’ warnings falling short, explaining why and how they are rarely right.

The Economists’ Great 2023 “Prediction”:

During 2023, the wider economy was in an interesting state. Inflation increased, but so did real wages, keeping unemployment in check. These macroeconomic trends gave off contradictory signals: stagflation suggested a recession due to a possible reduction of spending from the Federal Reserve’s aggressive interest hikes, yet wages indicated that employment was strong and firms would higher their working capacity.

Hence, experts faced a new dilemma: was a recession incoming, or were we headed for an expansionary phase? Economists, puzzled by the problem, looked for other evidence to break the balance between these two indicators. Many looked into Ukraine’s war as a catalyst for halting supply chains, though it had long cooled in the macroeconomic environment. Others investigated the real estate market crash in China, which signaled a loss in consumer confidence in the greater economy. This was supported by Bay Area housing sales declining nearly 24%, along with unwarranted inflation indicated by a 6.6% housing price increase, suggesting a cost-push inflation. The tech sector also saw massive layoffs, implying the employment uptick was only a temporary phenomenon.

Economists gathering the evidence believed the bearish sentiment was clear: consumer spending would likely decline as the Federal Reserve’s efforts to maintain inflation failed, leading to declining discretionary spending, increased unemployment, and a wider recession. As they released the news to the public, everyone sat back and prepared for the ever-looming recession to hit. Yet, it never happened. Why?

The resilient labor and consumer market:

To begin with, the labor market and consumer market were far more resilient than economists imagined. While massive technology companies such as Alphabet, Meta, and Amazon had massive layoffs, the broader economy remained afloat in terms of unemployment. Most companies were still focused on increasing revenue through marketing. More importantly, consumers were buying. As evident by consumer prices rising for all items at an average of 3.4% from December 2022 to 2023, consumer confidence was not completely bearish, with many heightening their purchasing activities.

Moreover, interest rates didn’t seem to faze consumers. Not only did credit card expenditure dramatically increase, but people carried more loans for longer periods of time—and at record-high interest rates, rapidly expanding the credit market. Importantly, mortgage rates were at 9-10% as well, yet housing demand never slowed as new families were eager to purchase homes at record-breaking rates.

As a result, the consumer market was never bearish to begin with, indicated by consumer expansion and real-estate demand at all-time highs in spite of global economic crises.

The government:

The US government created a “soft landing” for the economy in two ways: the over-packaged fiscal stimulus and a unique monetary policy.

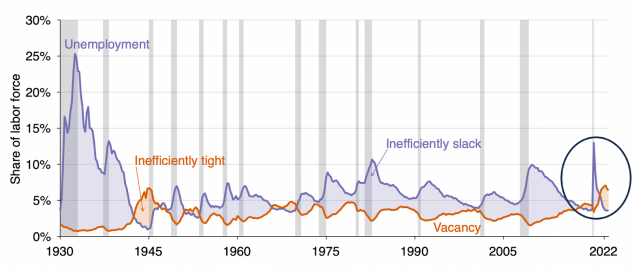

The stimulus was far more exaggerated in its inflationary impacts. It caused a significant “crowding out” effect. While vacancy (available job spots) was inflated compared to unemployment, relative to the COVID stimulus, it was relatively beneficial. The market corrected itself toward a soft landing.

Fig 1. Unemployment versus vacancies, where vacancies exceeded unemployment after the fiscal stimulus (Source: Pascal Michaillat, Emmanuel Saez, 2011)

Furthermore, the stimulus was accompanied by a cautious Federal Reserve, who kept a close eye on inflation rates. It immediately adjusted to cost-push and demand-pull inflation by raising interest rates up to 5.33%. Unlike Volker, who believed that a man-made recession scheme was necessary to create a rebounding economy, Jerome H. Powell was willing to adjust interest rates by 25 basis points per month, which engineered a successful soft-landing and prevented any form of economic slowdown.

What it can tell us about economics:

While economists are often viewed as pillars of logic, the world is far too complex and random to be quantified by intellectual understanding. Though they’re often more wrong than right, economists generally keep the economy on the right path. In reality, no one can predict the future. Perhaps we should use this as a cautionary tale that the world is too chaotic to predict. We must prepare for the worst but hope for the best.

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.