Writer: Saniya Pendharkar, Editor: Davina Yashar

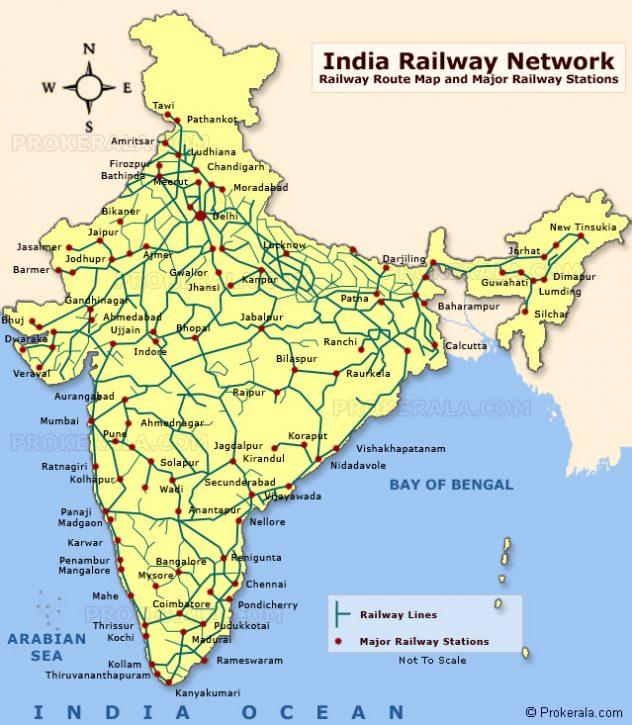

All Aboard The Railway Train! Today, we will be one of the twenty-five million passengers who ride Indian trains every day. In the most populous country in the world, the railroad is one of the most exciting, yet important aspects of Indian life. As the true lifeblood of India, the railroads crisscross the nation in their meticulously organized yet chaotic manner to meet the economic, social, business, and leisure-oriented needs of their passengers.

Along the beautiful Western coast of the country spans the 470-mile Konkan Railway. Renowned for its scenic beauty, the Konkan Railway is an engineering marvel that opened in 1998 after less than just ten years of construction. The track spans from the bustling financial hub of Mumbai in the state of Maharashtra to the major industrial port city of Mangalore in Karnataka.

The Konkan railway, like many railways, made a significant impact on the way of life in its surrounding region. In this article, I analyzed the major socio-economic effects of the railroad primarily in regards to labor and labor economics. I have accomplished this primarily by the analysis of two reports by Sreeja Jaiswal and Gunther Bensch: Evaluating the Impact of Infrastructure Development: A Case Study of the Konkan Railway in India and The Socio-Economic and Environmental Impact of a Large Infrastructure Project: The Case of the Konkan Railway in India.

Figure 1: Map of Konkan Railway

Photo by Peter Christener and Uwe Dedering

Figure 2: Map of Indian Railroads

Photo by Prokerala

In almost all cases, large transport infrastructure ventures lead to a significant trade-off, especially in developing countries. On one hand, the affected regions generally experience an economic boom since the railways bring more job opportunities. Additionally, the connectivity brought about by a new transportation project increases regional integration which is positively associated with economic growth since it facilitates the flow of trade, capital, and people between otherwise isolated areas. However, regions also experience labor displacement, changes in the initial style of living, and even serious environmental issues.

An expectation of large-scale transport projects is that the costs of transport in the respective region decrease while the time saved for passengers and freight increases. Indian railways are government-owned enterprises with the government subsidizing a significant portion of the operational and maintenance costs. This eliminates the need for rail systems to charge high prices since they are not entirely dependent on ticket sale revenue to manage the service. Additionally, the sheer number of passengers, I mean twenty-five million a day, translates to roughly eight billion journeys a year, allowing for economies of scale. With affordable fares, Indian railways play a major role in providing affordable transportation to the economically disadvantaged, leading to stark changes in the economic behavior of households and firms.

In the case of the Konkan Railway, the aforementioned tradeoff and changes in economic behavior are precisely what was observed in both of Jaiswal and Bensch’s reports. Through this railway, the Western Coast was able to diversify into non-agricultural economic activities. Economic diversification refers to the shift of an economy away from a single source—in this case, agriculture—towards multiple new sectors. The improved transportation infrastructure brought about diversification into various manufacturing industries, while increasing commerce and even boosting tourism.

The reports noticed there was an increase in the crude workforce participation rate in areas that were near the train stations; this value refers to the percentage of the working-age population that is actively employed. Interestingly, the increased rate was especially defined in non-agricultural sectors, further concluding that the Konkan Railway led to economic diversification.

Increased economic opportunity and industrial diversification are typically seen in all of India’s greatest railroad projects. However, one unique, fundamental impact of the Konkan railway project was that the connectivity of the railway allowed for more accessible economic opportunities, which reinforced existing migratory patterns. The Konkan region has had the historically definitive feature of male outmigration. The region has had strong migratory links to Mumbai, the capital of Maharashtra, and one of the greatest financial, commercial, and business centers of the world. With the end of the steamship routes into Mumbai in the late 20th century, land was the only way to travel, so the introduction of the Konkan Railway became an integral part of labor mobility in the region.

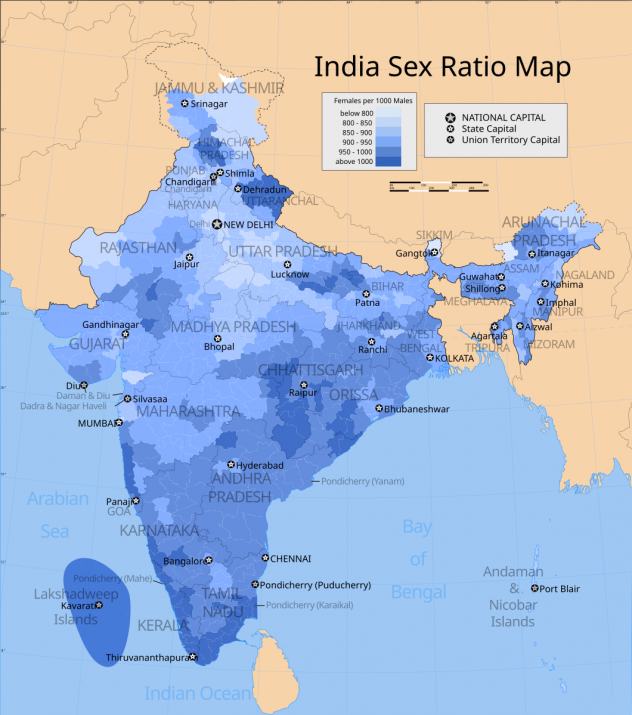

As a result, due to male outmigration, these migratory patterns substantially increased the female-to-male sex ratio in certain cities and decreased it in others The convenience and affordability of the Konkan railway saw the permanent move of male populations from their rural hometowns, to metropolitan areas that provided better economic opportunities. For example, the terminal city Mangalore experienced severe male outmigration; today, the sex ratio sits at 1016 females per 1000 males. This is much higher than the sex ratio for Karnataka, the state in which Mangalore resides, which has a ratio of 973 females to 1000 males. On the other hand, Mumbai was the destination for many male migrants. Now, the city has a sex ratio of 832 females to 1000 males while the state of Maharashtra has a ratio of 929 females to 1000 males. Other examples can be seen in the sex ratio of Ratnagiri (over 1000) which experienced male outmigration and the ratio of Goa (under 960) which received many male migrants.

Figure 3: Map of sex ratio in India. Darker areas have a greater number of females per 1000 males. Along the West Coast, the statistics align with what was discussed in the reports: lower ratios towards the North (where Mumbai and Goa are) and higher ratios to the South (where Managolre and Ratnagiri are.)

Photo by Planemad

A smaller, yet important effect to note is the population (and thereby labor) shifts that many regional industries experienced. Cities that were near railway stations witnessed a boom in population due to job-related migration. Consequently, the number of agricultural workers decreased because a new railway maintenance or construction job seemed more certain than a fruitful harvest season. This further contributed to the male outmigration initially discussed.

With any large-scale infrastructure project, transportation-related or not, one of the largest concerns is the corresponding environmental impact. This was particularly worrisome with the Konkan Railway. The railway spanned the Western Ghats, a mountain range of exceptional biodiversity and dense forestry; thus, many environmentalists argued that its construction would be destructive to the environment, especially with regards to deforestation. However, the research in Jaiswal and Bensch’s reports disproves this narrative, as there were no significant levels of deforestation— likely due to the project’s meticulous afforestation efforts.

These reports are crucial to understanding the nature and ramifications of the Konkan Railway. Both reports used a combination of interview-driven data collection and quasi-experimental research design to achieve their findings. In doing so, Jaiswal and Bensch were able to assess the significant socio-economic impacts of the Konkan Railway in Western India. The railroad increased the connectivity of the coast, mobilizing a plethora of economic opportunities that then allowed for greater economic diversification across regions. Additionally, even though the sex ratios became heavily skewed in many cities, it is unlikely that this had many negative economic effects on the individual or familial level. Think of it as a foot in either economy; the men leaving would still be participants in the economy they left behind, as they would be sending money back to their families; the men arriving, similarly, would be adding to the labor pool within their destination. Thus, the skewed sex ratios were not likely to have caused major domestic economic issues.

It can be conclusively determined that the Konkan Railway was, above all, a force for good. It’s initiated a number of efforts for greater regional mobility and economic development. The Railway project is a testament to the notion of interconnectedness–from coastal cities to the heartland, India deserves a force that unites and uplifts. So, in short, all aboard the railway train!

Featured Image by Rathnaswamy Allwin