Writer: Aidan Morgan Chan | Editor: Davina Yashar

For decades, Kazakhstan has ridden the waves of its natural abundance. Its economy is largely fueled by oil and gas exports, which account for nearly a third of its government revenue. However, this reliance on a single sector has left the nation vulnerable to the unpredictable forces of global markets, underscoring the need for economic innovation and forward-looking progress. The upheaval brought on by the pandemic in 2020 was a stark reminder of these vulnerabilities as oil prices plummeted and Kazakhstan’s GDP shrank under pressure. Under the Kazakhstan 2050 Strategy, the country has set its sights on building a more diversified economy—one which may allow the country to finally pursue economic ambitions under a newly-powered framework. However, the question remains: Can Kazakhstan successfully transition away from its dependency on primary commodities to achieve economic autonomy?

The Density of an Oil-Based Economy

The nature of oil dependency has been described as a source of political predation. Such markets in capitalism have notably produced enclave economies governed by an imperial mandate often characterized by violence and instability. Though Kazakhstan’s political economy doesn’t explicitly reiterate the intrinsic animosity within the market, Kazakhstan’s economic purview is befitting of an enclave designation. Hydrocarbons contributed to as much as 20% of total GDP in 2023 and in December 2023, oil exports averaged 1,424.583 barrels per day, a record increase from 1,315.167 barrels per day in 2022. Moreover, data shows that Oil Real GDP Growth in Constant Prices is forecasted to further increase by about 14.37% in 2025. Though 20% is a smaller fraction, the annals of oil have been at the center of Kazakh macroeconomic policymaking for quite some time.

Kazakhstan, endowed with its oil-oriented fiscal revenue, is inevitably subject to external volatility such as increasing interest rates, pricing fluctuations, and interrupted supply chains. This is simply the nature of oil-based capitalism. Thus, despite expressing efforts to enhance fiscal policy and resource allocation, Kazakhstan doesn’t have much certainty regarding how fluctuations in oil may burgeon into issues conflicting with their economic stratagem. Subsequently, their dependence on such a volatile export dynamic has resulted in increased quasi-fiscal expenditures which weakens economic infrastructure by complicating the governance of financial reserves.

More often than not, off-budget spending to bolster crude oil has undermined non-oil budget revenues, neglecting essential social spending like education. According to the Human Capital Augmented Solow-Swan model, this strategy does not promote sustainable progress, as it allocates resources inefficiently. Improving the welfare of one sector comes at the opportunity cost of investing in areas critical to long-term growth, such as human capital development.

This dependence not only constrains economic diversification but also heightens vulnerability to external shocks. A substantial decline in any single commodity price can severely impact export revenues, as evidenced in other commodity-dependent nations where such downturns have precipitated reduced public investments and increased public debt. Furthermore, the United Nations Trade and Development institution highlights that 85% of the world’s least developed countries exhibit commodity dependence, with 29 out of 32 nations with low Human Development Index (HDI) scores reliant on commodities dominating an average of 82% of total exports. This correlation underscores the broader implications of economic dependency, which frequently results in diminished public services and overall development.

The Crude Nature of Geopolitics

With trading partners like China, Russia, and Turkey, Kazakhstan’s service in bolstering the global supply chain has inevitably resulted in the formation of a multi-vector policy tethered to crude oil contracts. This has caused the country to be situated awkwardly at the crossroads between conflicting geopolitical interests and ideologies of the great powers, despite them seemingly wanting to undertake a passive role as a third-party agent. However, Kazakhstan and other Central Asia states have always been the target of exploitation by their neighbors. Their natural wealth in energy and minerals, paired with their prime geographic location between the Middle East, China, Russia, and Eastern Europe, made them desirable on many fronts. As such, they were forced to play a more active role in the region to defend their sovereignty. However, despite oil giving Kazakhstan a trump card, to what extent are their trade structures autonomous?

Once affiliated with the USSR, Kazakhstan and Russia have a long history of interdependence. Though Kazakhstan has made an effort to pivot away from Russia in recent years, its overdependence on the oil sector, once again, is an issue. About 80% of Kazakhstan’s crude oil exports are dependent on the Caspian Pipeline Consortium. Thus, Russia’s control of export networks means that Kazakhstan’s ability to conduct trade depends on the Kremlin. In March 2024, Russia indirectly intervened in Kazakhstan’s efforts to increase oil exports to Germany after the suspension of the Druzhba Pipeline due to legal troubles. Accordingly, investor sentiment toward Kazakhstan has become more restrained, influenced by Russia’s monopolistic control over regional export channels and trade networks.

However, as Russia’s presence in the region begins to wane under the shadow of the ongoing conflict in Ukraine, China is moving in to solidify its influence in Central Asia by capitalizing off of this geoeconomic fragmentation. The ambitious Belt and Road Initiative is beginning to manifest in Kazakhstan, with President Xi looking to cement trade routes and secure access to energy resources. By linking Asia with Europe, China hopes to revive the conduit through which goods, resources, and capital can flow as they once did on the Silk Road. But for Kazakhstan, this emerging partnership brings both the allure of investment and the specter of overreliance once more—they can’t afford to repeat the same mistakes made by lacking divergence from Russia.

It seems that for Kazakh leaders, the task ahead is one of careful diplomacy: establishing a robust and balanced economy compels the nation to navigate both old dependencies and new allegiances in order to reduce its vulnerability to the vicissitudes of any single trading relationship, whether with China, Russia, or beyond. It seems that this will only be possible through diversification from oil.

Comparative Advantage is Relatively Disadvantaged for Kazakhstan’s Diversification of Commodities

Though the obvious undertaking here would be to pivot away from this oil-backed economy, this compels us to question Kazakhstan’s other options–and whether they are feasible for long-run economic growth. Kazakh leaders have proposed adapting their economic infrastructure under a mineral-based and agrarian framework–recently establishing new trade agreements between Singapore, the United Kingdom, and Germany to reap the abundance of rich mineral deposits in Kazakhstan.

As the global demand for critical minerals continues to increase, the industry offers vast promise and untapped potential. However, Kazakhstan faces an issue as its lack of foreign investments (once again due to its complex geopolitical dynamics) indicates that it doesn’t have the necessary means of funding extraction. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development estimates that Kazakhstan is depleting its mineral reserves while concurrently not having the means to further finance exploration to replenish its stock.

Moreover, World Bank diagnostics indicate that the Kazakh government has not developed any consistencies in artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM). The informal nature of Kazakhstan’s ASM industry, characterized by a lack of industry regulation and formality, renders the market inaccessible to financial markets, limiting its contribution to the supply chain. This situation is particularly concerning as the global economy transitions toward sustainable practices. Countries must acknowledge the risks associated with resource stranding, highlighting the ongoing pursuit of minerals critical for clean energy and the necessity of avoiding a narrow focus on commodities.

These efforts to diminish oil’s status as the apex commodity have also compelled economists to evaluate the feasibility of sustaining industry profitability and social welfare. The anticipated cost surge associated with reduced oil dependency will inevitably introduce a balancing mechanism, compelling firms to redirect capital toward alternative resources. According to input substitution theory, firms seek cost-effective alternatives, reallocating resources to minimize expenses. However, the inability to follow isoquant analysis effectively–due to limited resources–means that firms will likely struggle to maintain output levels with less input. This shift will lead to a reduction in employment capacity, particularly in monotowns, where dependence on a single industry makes the impact of job displacement much more pronounced. As a result, the burgeoning of unemployment will reduce social welfare and thus human capital.

Kazakhstan has turned its gaze toward sectors like agriculture in order to combat its lack of economic diversification. With an abundance of rich land, the country has the potential to become a regional breadbasket. However the International Trade Administration reported in 2022 that about 75% of Kazakhstan’s land mass is arable, yet only about 30% of the land is under agricultural production. Furthermore, like the mining sector, agriculture is subject to external volatilities. As documented by the United States Department of Agriculture, Kazakhstan is at risk of water scarcity and yields may decline anywhere from 9% to 47% by 2030. This will likely result in food scarcity and labor shortages as about 30% of Kazakhstan’s working economically active population depends on this industry. Despite having a comparative advantage in Mining and Agriculture, Kazakhstan is unfortunately not at an economic advantage due to its lack of conditional agency.

Sowing the Seeds of Prosperity

In light of these challenges, the Theory of Second Best suggests that if Kazakhstan is unable to achieve an optimal economic balance by diversifying fully away from oil, it may still improve overall welfare by strategically investing in mineral and agricultural sectors. While these investments may not meet all ideal economic conditions, they could serve as compensatory measures, allowing Kazakhstan to make meaningful progress toward sustainable growth under current constraints. Kazakh leaders, despite all odds, are optimistic and have made notable efforts to restructure their export commodities this year.

The European Union along with countries like China and Afghanistan have also signed agreements to establish new trading partnerships. To capitalize on this potential, Kazakhstan must look beyond merely establishing partnerships and focus on developing a comprehensive strategy to diversify its economy effectively. While trade agreements are projected to boost Kazakhstan’s GDP by as much as 5.5% by 2025, the country still faces the challenge of limited export commodities. This lack of diversification restricts Kazakhstan’s ability to achieve self-sufficiency and exert greater control over its trade dynamics. By strategically strengthening its economic framework, Kazakhstan can pave the way for long-term growth and resilience.

Recognizing these efforts, the global financial community has taken notice: recent diversification measures have led to an upgrade of Kazakhstan’s credit rating to ‘Baa1’ by Moody’s—the highest in the country’s history—marking a significant milestone in the country’s pursuit of economic stability and growth. As Moody recently cited improved fiscal stability, a diversified revenue base, and robust foreign reserves, their findings seem to echo Kazakhstan’s optimism about its economic future.

A Bold Step Toward Global Credibility and Regional Influence

As the nation begins emerging from its reliance on oil and gas, Kazakhstan’s potential return to international capital markets through a dollar-denominated bond issuance signals a profound shift. By issuing bonds in the Dollar, Kazakhstan seeks to bolster its reputation on the global financial stage, inviting investors from beyond its borders to partake in its growth story. A successful dollar bond would diversify Kazakhstan’s investor base and represent an opportunity for the nation to underscore its commitment to international financial standards. And yet, this is more than a quest for capital—it is a bid for the country’s very identity as it aspires to be seen as a stable and credible partner in the global financial ecosystem.

Cultivating trade partnerships that transcend traditional dependencies will mitigate reliance on any single economic partner. By capitalizing on its comparative advantage in natural resources and leveraging its strategic geopolitical position, Kazakhstan can forge a diverse array of trade relationships that enhance its competitive standing in the global marketplace. This diversification of both trade partners and economic outputs will empower Kazakhstan to better withstand external shocks, optimize resource allocation, and capitalize on emerging opportunities in dynamic global markets.

Resilience and Renewal

Kazakhstan is at a critical juncture where the strategic decisions made today will reverberate throughout its economy for years. The journey toward economic diversification necessitates a comprehensive approach that addresses immediate fiscal imperatives and fosters long-term sustainability and resilience. Embracing an adaptive policy framework that promotes innovation and value-added production across sectors—particularly mining and agriculture—will be pivotal in constructing a more balanced economic architecture. However, the principles of comparative advantage still illustrate that while a country may excel in the production of certain commodities, excessive reliance on these resources will likely yield adverse consequences–and this is something Kazakhstan needs to be careful about.

Economic diversification offers numerous benefits for all economies, including enhanced resilience against market volatility, creating higher-quality jobs, and facilitating structural transformation across industries. By broadening their economic bases, countries can reduce vulnerability to external shocks, stabilize export revenues, and promote sustained growth. This diversification is crucial for immediate economic stability and fostering innovation and sustainable development that can benefit future generations.

Overall, Kazakhstan’s quest for economic resilience reflects broader regional dynamics and offers valuable insights into the complexities of resource-dependent economies navigating a rapidly evolving landscape. The urgent need to extricate itself from commodity dependence highlights the importance of implementing robust green industrial policies. By strategically investing in human capital development, enhancing infrastructure, and building institutional capacity, while simultaneously seeking to elevate its global profile through initiatives such as dollar-denominated bonds, Kazakhstan can chart a course toward a more self-sufficient and resilient economic future. The nation’s journey serves as a microcosm of the broader shifts occurring in Central Asia—a region once overshadowed by powerful neighbors, now emerging as a crucible of opportunity and change.

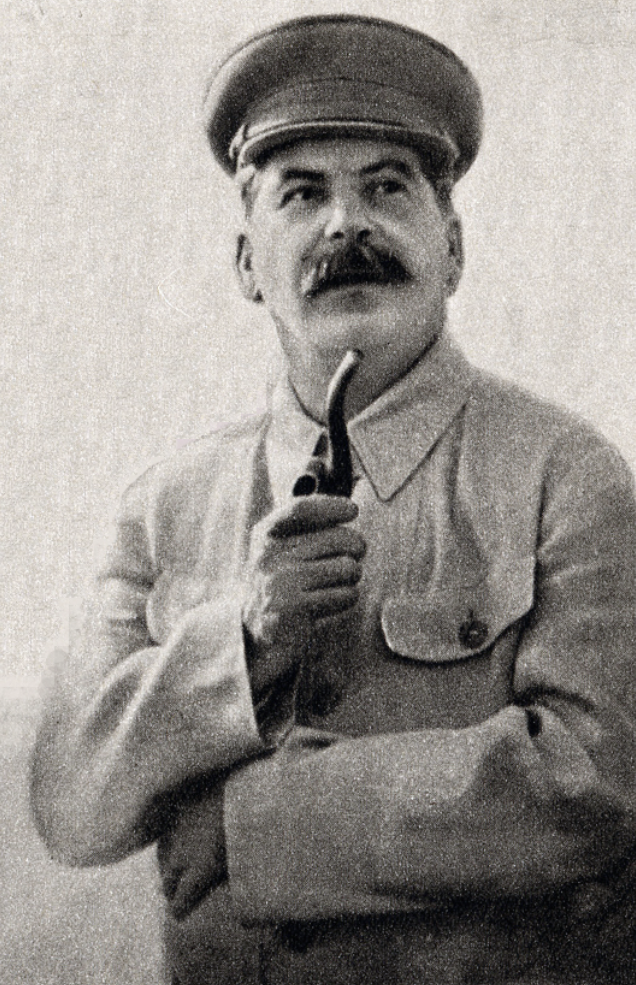

Featured image by The New York Times