Written By: Tanvi Garg | Edited by: Selina Yang

Decisions, decisions, and more decisions. As the new Trump administration rolls in with tariff after tariff against goods from Mexico, Canada, and China, some Americans are left wondering what it means for their annual spending. Others are enthusiastic about potentially higher wages and more demand for their labor. That sharp divide raises several questions: Who is right? Will Trump’s tariffs affect most Americans negatively, positively, or not at all? How can we tell?

The short answer is game theory. Aside from its role in poker and other casino games, game theory is highly useful. While there are several ways to analyze political decisions, some economists lean on this branch of the field to consider strategies, beliefs, and the expected “utility” with each possible outcome between different “agents.” Game theory can reduce political interactions and economic decisions to simple mathematics, so while some nuances can be lost along the way, it’s a good starting point when assessing tariffs.

Cooperative/Non-Cooperative Game Theory & Efficiency

Before analyzing the efficiency of tariffs, let’s break down game theory into something more digestible. In the simplest of terms, game theory contains two models: cooperative and non-cooperative. Cooperative games deal with “agents” (in this case, countries) who tend to form coalitions with each other based on shared primary objectives, which results in the agents cooperating for a collective payoff. Usually, this means setting some of their self-interests aside for the greater good. In the real world, this shows up in international agreements like the Paris Agreement, USMCA (formerly known as NAFTA), EU Customs Unions, etc.

On the other hand, non-cooperative game models exist as well, where agents are in a competitive environment, prioritize their self-interest, and try to maximize their individual payoff. Think of Rock-Paper-Scissors; if the outcome player 1 is trying to achieve is winning, in the case where player 2 plays “rock”, it would be in the first player’s best interest to play “paper”. To simplify, if the desired outcome (typically characteristic of a zero-sum game) is a win, it is within a player’s best interest to play a best response to their opponent’s strategy, pitting their interests and best responses against another’s. Now, it seems obvious that trade wars are non-cooperative game models. So, how do countries determine whether to pursue a cooperative game model (trade agreement) or a non-cooperative game model (trade war)? Yes, by looking at either the Pareto-Efficiency of a payoff or whether the outcome they’ll achieve is a Nash Equilibrium, and which is better.

Pareto-Efficiency vs. Nash Equilibria

Pareto Efficiency and Nash Equilibria are two terms that tend to be thrown around when discussing game theory. So then, what does it mean for an outcome to be Pareto-efficient or a Nash equilibrium; how do they differ? An outcome can be classified as a Nash equilibrium, specifically when dealing with non-cooperative game models, when an agent acts on their belief of their opponent’s strategy and chooses the best response accordingly. As such, outcomes where both opponents choose best responses to create a “mutual best-response” are known as Nash equilibria. Alternatively, Pareto-efficiency is used to determine optimal outcomes in cooperative model games, where an outcome is classified as “Pareto-optimal” or “Pareto-efficient” if it can benefit at least one agent without making any other parties worse off.

So, how does this tie into trade wars? When countries engage in trade wars, they usually enact tariffs against each other in such a way that they prioritize their economy and let tension grow in the political relationship. This means that the strategies they use against each other result in Nash equilibria, or their best responses in a non-cooperative model. Unfortunately, trade wars are often not the best response, if we were to follow game theory doctrines, even with the downsides of FTAs (Free Trade Agreements). The best choice for most countries would be to engage in a cooperative model, where they prioritize outcomes that are “Pareto-efficient” for both parties.

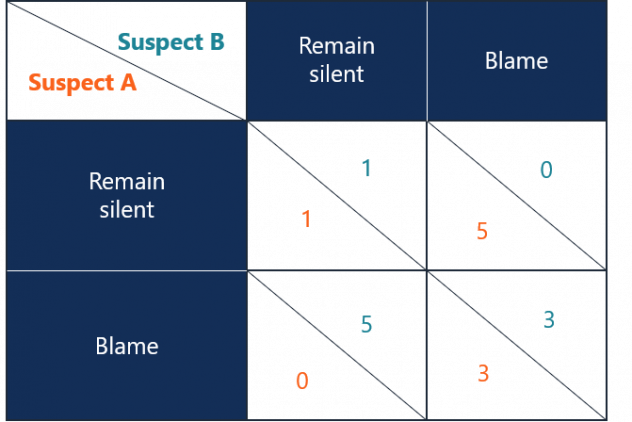

Take, for example, the Prisoner’s Dilemma. It’s a classic problem that asks whether you should rat out your friend for a crime to try to get the best deal (getting off scot free while they get five years) or cooperate by keeping quiet and only staying in jail for a short time (one year). If both of you rat on each other, you get three years. Now, the strategy that most players choose, and what is also the Nash Equilibrium (since this ends up being a non-cooperative model), is for both players to defect. That way, no matter what the other player does, neither player ends up with the worst outcome. With both players defecting, they both get three years. But that’s not truly the best outcome. Both players could cooperate and serve for only one year. This goes to show that what might be considered the Nash equilibrium in a non-cooperative model might not be the best outcome, or what is “Pareto-optimal,” if both parties just cooperated instead.

Disclaimer: Although “Pareto-efficiency” is used to represent one of the most optimal outcomes in this article, and similarly in cooperative game models, it is not equivalent to an outcome being “fair”, and it doesn’t rank Pareto-efficient outcomes. As mentioned earlier, this is where some of the nuance is lost when considering basic game theory to evaluate political and economic decisions.

Previous Trade Wars in the U.S.

It’s important to remember that this isn’t the first time the U.S. has engaged in a trade war. Let’s take a look at some of the tariffs enacted in the past.

Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act: This tariff act of the 1930s crippled the U.S. during the Great Depression, and added to the already high tariff rates. Although well-intentioned initially, to save American farmers from intense international competition after World War I, this act led to American exports to fall by anywhere from 18% to 61%. Furthermore, US imports decreased by a whopping 66%, and unemployment rates doubled due to the high tariffs (from 8% to 16%) and the Great Depression.

US Steel Import Tariffs: In 2002, the Bush administration placed import tariffs of nearly 8% to 30% on steel from a majority of countries aside from Canada, Mexico, Israel, and Jordan. As a result of these tariffs, steel prices skyrocketed, which led to nearly 200,000 jobs lost and the shift to international manufacturers instead of US producers of products with steel.

U.S. v. Canada Lumber Dispute: This ongoing trade war started back in 1982 over the claim that since provincial governments subsidized Canadian timber, it was unfair to American wood companies, which were mostly privately owned, to compete against Canadian timber. As a result, the U.S. wanted to subject it to a “countervailing duty tariff” to even out the commodities. Although an agreement was reached in 2006, the Biden administration moved forward in 2024, almost doubling tariffs from 8.05% to 14.54% on softwood lumber from Canada. Now, the Trump administration wants to raise these tariffs to nearly 40%, adding a 25% tariff to the previous tariff, leading to a potential increase in housing prices.

The Current Tariffs

Take into account how previous trade wars have gone for the U.S. and the usefulness of game theory in analyzing these trade wars. Now, let’s take a look at what tariffs Trump and his administration have proposed, as well as how efficient the current tariffs would be. Based on the White House “Fact Sheet”, as well as President Trump’s interview, which he gave on March 23rd, the following tariffs will be implemented within the next month:

- 25% additional tariff on imports from Canada and Mexico.

- 25% tariff on Steel and Aluminum

- 25% on semiconductors, and autos

Q: Would the tariff on imports from Canada and Mexico be a NE or a Pareto-efficient outcome?

The tariff wouldn’t be a Nash Equilibrium since this strategy would be dominated by the strategy of either imposing tariffs on countries other than our closest allies or not imposing a generic tariff. Usually, disputes over sugarcane, steel, aluminum, and lumber are the only issues between the U.S., Canada, and Mexico, but this tariff would affect most imports.

This tariff wouldn’t be Pareto-efficient since a better outcome would include honoring the USMCA a bit more strictly, which would lead to better relations between the U.S., Canada, and Mexico. If the U.S. is not concerned with the payoff, including diplomatic relations, but rather only with how well the U.S. economy performs, it still wouldn’t be a Pareto-efficient outcome. This is due to retaliatory tariffs that Canada has already put into place, which Mexico might follow.

Q: What about the other tariffs?

It’s harder to say, but for steel and aluminum, based on how tariffs on imported steel goods went in 2002 under the Bush administration, it likely wouldn’t yield a Pareto-efficient or Nash equilibrium outcome. The last time Trump was in office and imposed steel and aluminum tariffs, employment and domestic production in metal industries did rise briefly. However, in the long run, according to William Hauk, a University of South Carolina professor of economics, “Though domestic production of steel and aluminum increased, it did not happen fast enough to bring prices back down quickly”. As for the tariffs on semiconductors and autos, it wouldn’t yield a Pareto-efficient outcome due to the nature of the non-cooperative model (tariffs), but there would be a slim chance for it to be a Nash equilibrium unless there were retaliatory tariffs, in which case the best response would be even more retaliatory tariffs.

Q: If tariffs are usually inefficient in the long run, why engage in them?

There are several reasons that people still believe in the efficiency of tariffs (aside from the fact that they don’t fail all the time).

People believe in tariffs because they believe…

- They protect “national interests.”

- They help workers.

- They can be a Nash Equilibrium for the U.S.

- Trump’s trade wars can be used to eliminate the U.S. trade deficit.

Are any of these statements true? Let’s take a look.

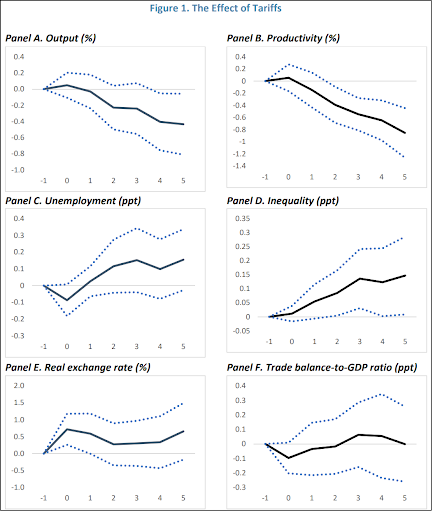

- Do tariffs protect “national interests”? The short answer is no, even if it seems like it. The longer answer is that in the short term, it appears as if tariffs are protecting national interests by allowing domestic industries to thrive instead of foreign competition. But national interests may not be the same as “middle-class” and “consumer” interests, since tariffs lead to higher prices in the country that imposes the tariff. Additionally, even “national interests” are harmed over time. The World Economic Forum (WEF) found that GDP falls if tariffs are imposed, leading to “a significant decrease in labour productivity”, a “small increase in unemployment”, and “greater inequality after a few years”. In fact, in the research paper “Macroeconomic Consequences of Tariffs” (Furceri et al., 2018), there’s a straightforward graph that shows the effect of tariffs.

Note. From “Macroeconomic Consequences of Tariffs” by Furceri, D., Hannan, S. A., Ostry, J. D., Rose, A. K. (2018), National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper, pg. 33

- Do tariffs help workers? Yes, tariffs can help some workers in the short term. It depends on the skill level of said worker, as well as what sector of employment they’re working in. In “Who Benefits from Trade Wars?” (Lechthaler & Mileva, 2018), it was found that in the import-competiting sector, “unskilled workers… would benefit from a trade war, while all other workers would lose out.” However, that conclusion can be drawn only if one considers that the opposing country doesn’t impose retaliatory tariffs. So what happens when retaliatory tariffs come into play? In a trade war, consumption will fall for all sectors, but there is still one group that fares above the rest: unskilled workers in the unskilled-intensive sector.

- Can a tariff be a Nash Equilibrium in the U.S.? Sure, it could be. But, usually, is it? Based on the history of tariffs in America and my previous analysis of the current tariffs that the Trump administration is either exacerbating or placing, it’s safe to say that most of the time, it isn’t.

- Can Trump’s trade wars be used to eliminate the U.S. trade deficit? Based on the last time Trump was president, it appears not. Firstly, a trade deficit refers to a situation in which a country imports more than it exports, and a trade surplus is when a country exports more than it imports. The U.S. had a trade deficit of nearly $131.4 billion in January 2025. During Trump’s last presidency, when Trump specifically started imposing tariffs on Chinese products, such as Chinese bicycles, according to Ana Swanson at the New York Times, “Chinese bicycle factories moved their final manufacturing… out of China, setting up new facilities in Taiwan, Vietnam…”. So, back in 2018, while U.S. imports from China were reduced to decrease the trade deficit, America’s trade deficit with other countries (Canada, Mexico, etc.) widened. Trump is doing the same thing during his current term, imposing more tariffs and initiating trade wars in hopes that the trade deficit will be lessened. But is a trade deficit bad? No, not necessarily. Andreas Freytag and Phil Levy at the Cato Institute analyzed Federal Reserve Economic data and found that “there is no evidence that higher trade surpluses… accompany higher GDP growth.”, and that as the trade deficit increased, “the unemployment rate goes down”. In fact, during a recession, the trade deficit will narrow, implying that the narrowing of a trade deficit isn’t always ideal.

Conclusion

The decision is in. Although there might be a perceived incentive to engage in a trade war, it harms the American economy and free trade in the long run. The biggest takeaway (for any presidents reading this) is to follow the “golden rule” before imposing tariffs or starting a trade war: Do unto others as you would have them do unto you. Based on Pareto efficiency, Nash equilibrium, and the history of previous American tariffs, it can be shown that tariffs in the long run don’t usually bode well for the American economy. Remember the Smoot-Hawley Tariff? The worst part about the entire tariff disaster was that trade was only 6.4% of the U.S. GDP at the time. Now, trade makes up more than 25% of our GDP. If Trump were to impose tariffs on countries armed with retaliatory tariffs, it might be even harder to recover than it was after COVID-19. And it’s not just a myth that retaliatory tariffs will happen. In fact, as of this week, Canada and the European Union have both announced their tariffs to push back against America.

Tariffs will not protect the American economy if we permanently lose our closest allies.

There is no winner in a trade war.

Featured Image by Felix Mittermeier on Unsplash