Writer: Richard Yun and Cynthia Shi | Editor: Vismaad Randhawa

In Seoul, the issue of homelessness is mostly constrained to people sleeping in subway stations during the winter. So, as an exchange student new to the Bay Area (and to the US for that matter), I was shocked at the sight I encountered as I exited the Civic Center / UN Plaza BART station. Multiple people were lying listlessly on the sidewalk, nodding off or, to my terror, injecting substances into their arms. I stood frozen, my gaze fixed on a syringe—now empty—until a panhandler approached me aggressively, snapping me out of my trance. Only then did I realize I was in the infamous Tenderloin district. As I made my way across the Tenderloin to Japantown, I saw at least 40 people living on the sidewalks. Some were noticeably suffering from mental illness, shouting expletives into the air, and others were doubled over in extreme positions, which I later learned is called the ‘fentanyl fold.’

The Tenderloin is a clear manifestation of the homelessness crisis that is prevalent in most of the big cities in the US. According to the most recent Point-In-Time estimates (PIT) of homelessness by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, roughly 653,100 people – or about 20 of every 10,000 people in the United States – are homeless. Six in ten people were experiencing sheltered homelessness—that is, living in an emergency shelter (ES), transitional housing (TH), or safe haven (SH) program—while the remaining four in ten were experiencing unsheltered homelessness in places not meant for human habitation.

A chronically homeless person, as defined by the HUD, is an individual with a disability that impedes their ability to live independently. They must also have been either continuously homeless for at least one year or have experienced at least four episodes of homelessness in the last three years, totaling 12 months or more. In 2023, about one-third (31%) of all individuals experiencing homelessness reported having experienced chronic patterns of homelessness, or 143,105 people, which is the highest number counted in the PIT count since 2007.

Housing First

To address the crisis, many states adopted the “Housing First” approach, which aims to provide the chronically homeless with permanent housing without requiring treatment for mental health issues or substance use disorder. The program is built on the philosophy that housing is a basic human right to which everyone should have access. Starting with Utah, many states made it the center of their homelessness policy responses. California now requires any state-funded homelessness program to abide by the principles of Housing First, including allowing tenants to stay housed regardless of substance use or mental health issues. Even the new federal plan to address homelessness, recently unveiled by the Biden administration, rests on this philosophy.

It makes sense why many states defaulted to this approach since, at first glance, Housing First appears to fulfill the criteria of being a friendly and easily accessible solution for the homeless. People expected the homeless population to drastically decrease in cities that have been plagued with the crisis for decades. Past research also endorsed the idea that the program would result in “quicker exits from homelessness and greater housing stability over time.” However, as years passed, the number of people on the streets didn’t appear to decline at all. On the contrary, the homeless crisis has only been worsening in recent years.

The lack of visible change to the homeless crisis led to skepticism about the effectiveness of Housing First; this sparked new debates over whether the program should be replaced or not. Proponents of Housing First argue that providing immediate housing is still the most effective approach at addressing homelessness and should stay at the center of the government’s response to homelessness. Others, however, demand that the funds be redirected to rehabilitation programs, favoring a traditional “stair-step” model that requires individuals to first address underlying issues, such as substance abuse or mental health challenges, before accessing housing. However, both arguments appear to be based on intuition and anecdotal evidence rather than data.

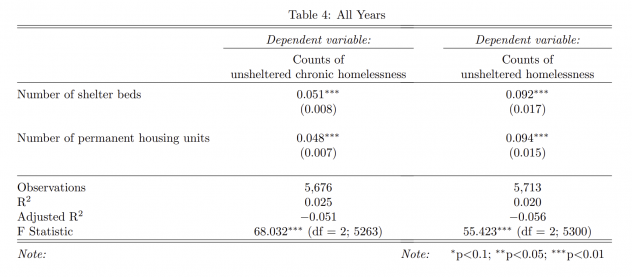

To contribute to the debate, we conducted an original empirical analysis using the PIT homelessness census and the Housing Inventory Count (HIC) published by the HUD. The HIC is a point-in-time inventory of provider programs within a CoC, a local planning body that coordinates housing services and funding for homeless individuals. Combining the yearly PIT census with the HIC, we estimated the causal effect of permanent housing projects, specifically Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH), on reducing the number of unsheltered homeless with a Two-Way Fixed Effects (TWFE) model.

TWFE controls for entity and time-fixed effects, allowing us to isolate the causal impact of housing policy on homelessness counts from the effects of time-invariant factors that are unique to a locality and from factors that change over time but affect the entire nation equally. For example, it will account for the warm climate in San Francisco when explaining the city’s sizable homeless population, as well as account for the nationwide economic downturn resulting from the financial crisis when explaining homelessness counts of 2008. However, it is important to note that our model is still limited because it does not capture the influence of region-specific factors that vary over time, such as the booms and busts of the tech industry, which are critical to understanding San Francisco’s housing and homelessness crisis.

The results are puzzling. Taken at face value, it shows that PSHs are actually increasing the number of unsheltered homeless. A story that might fit this result could be that maybe shelters and PSHs are so poorly managed that they are becoming drug hotspots, exacerbating the crisis by making drugs more accessible. Perhaps this may happen on rare occasions. However, a far more plausible explanation would be that the model is misspecified and suffers from omitted variable bias or endogeneity arising from reverse causality. A strong possibility is a situation of reverse causality, where CoCs that saw a rapid increase in homelessness built a lot of PSHs in response to the increase, rather than PSHs generating more homelessness.

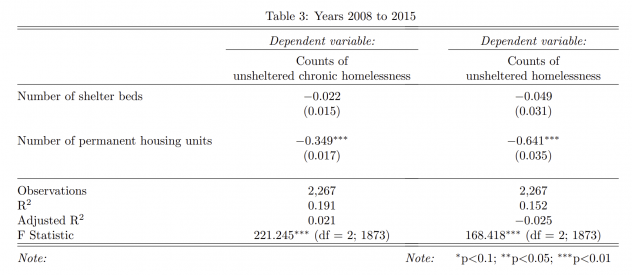

Further analysis lends support to this scenario. When we limited the sample to the years 2008 to 2016, before Housing First was widely adopted, the model yields numbers that make much more sense. When regressed on the overall unsheltered homeless population, the coefficient on the number of PSH units was -0.64, meaning that an additional unit reduces 0.64 incidences of homelessness. On the other hand, the coefficient on the number of shelters is only -0.04, and is not statistically significant. Limiting the sample to unsheltered and chronically homeless individuals gives similar results. An additional PSH was shown to reduce 0.34 incidences of chronic homelessness, while shelters were estimated to reduce 0.02, again being statistically insignificant. The causal effect of an additional PSH on reducing the number of homeless people, 0.34, may seem small in magnitude, but it is certainly nontrivial. Considering that the chronically homeless are often those with various underlying problems that are very difficult to treat, it is actually fairly impressive. Meanwhile, traditional emergency shelters appear to fall short when it comes to accommodating the homeless.

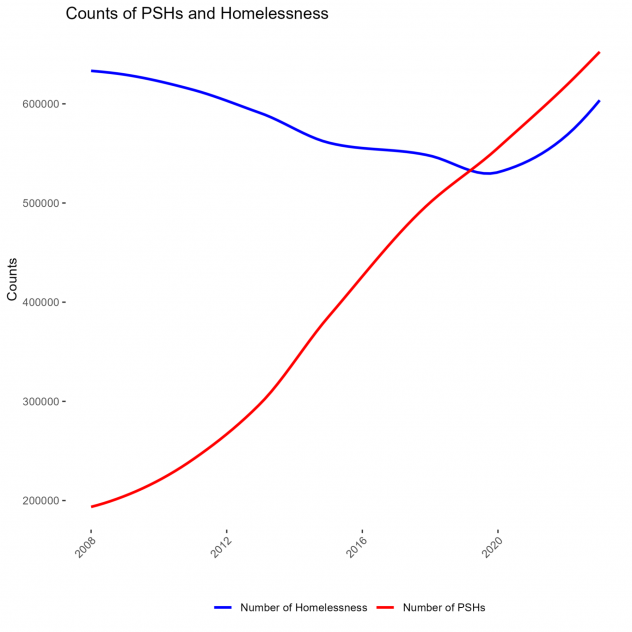

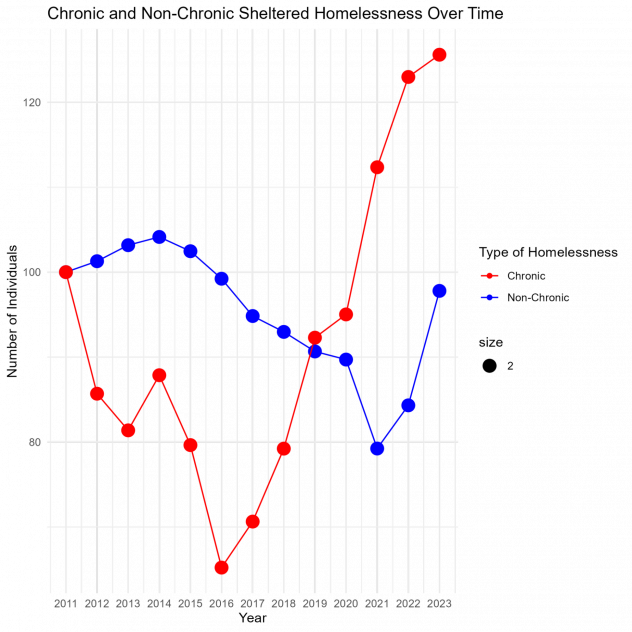

Therefore, the efficacy of PSHs is apparent in the earlier years of their implementation. Contrary to what many critics say, Housing First did not fail upon implementation, but rather performed fairly well. The program’s effectiveness encouraged politicians to push for stable housing, making the provision of PSHs a central policy objective to combat homelessness. However, as illustrated in the graph below, shortly after 2016, unknown changes caused an exponential increase in homelessness, resulting in more PSHs being constructed. Observing the homelessness crisis actively worsening while, at the same time, more PSH units were being built, many rushed to the conclusion that Housing First was at fault without further analyzing its actual causal effect in treating homelessness.

Renter Supportive Policies

Permanent Housing is not the only avenue of homeless policy that warrants a more careful assessment of its impact. People have repeatedly claimed that renter-supportive policies would be more effective at reducing the homeless population. Namely, Eviction Moratoria and the Emergency Rental Assistance Program (ERAP) are renter-supportive policies that target low-income renters who are at risk of being evicted. Policies in this vein reduce homelessness by preventing evictions, the major precursor and cause of homelessness. According to the National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty, reports conducted on the homeless population showed that evictions are one of the leading causes of homelessness; 14% of people in the Santa Cruz County area reported it as the primary factor in becoming homeless. In New York City, it was 33%.

Studies have found that eviction prevention policies are indeed effective at helping people retain their homes. For instance, research conducted by the Eviction Lab at Princeton University revealed that during the pandemic, eviction case filings were lower in states that slowed or paused eviction proceedings. They also found that eviction filings were cut more than half between the start of the pandemic and 2021, falling to historic lows. The decline in homelessness shown in our graph and the historically low numbers of non-chronic homelessness in 2021 is another piece of evidence that attests to the efficacy of Eviction Moratoria and rent relief.

While these measures have been generally effective, they only address one side of the crisis. Chronic homelessness, as opposed to non-chronic homelessness, does not seem to have responded to the COVID-era renter support policies at all. In fact, the rate of chronic homelessness has actually risen. 2021 was the year that chronic homelessness saw its sharpest increase, in stark contrast to the trend for non-chronic cases. Moreover, chronic homelessness has been worsening in recent years, displaying a continuous increase in all years since 2016. In contrast, counts of non-chronic homelessness gradually decreased in the years leading up to the pandemic.

This suggests that renter-supportive policies, which have been the focus of housing authorities ever since the pandemic, simply don’t work when combating chronic homelessness. This should not come as a surprise. Those who are at risk of being evicted and becoming homeless for the first time, and those who have been homeless for more than a year, are very different groups of people. The latter are far more likely to have debilitating mental and physical health problems that greatly affect their ability to work, which leads to increased odds of being deprived of a safety net provided by friends and family. They are also more likely to have substance abuse problems. Studies done at UCLA have shown that “more than 75% of [the chronically homeless] have a serious mental illness, and 75% have a substance abuse problem, and the majority have both.” Conditions like these severely limit the capabilities of these individuals to take advantage of these renter-supportive measures. Therefore, to get people “off the streets,” on top of preventing future homelessness, policies should address these underlying problems directly. Without substance control programs and mental health treatment, rental market interventions simply are not enough to help the most vulnerable. Naturally, these policies should be kept and continuously improved upon, but they should not be relied on as the sole solution for homelessness.

On January 14, 2025, New York City comptroller and mayoral candidate Brad Lander called for an expansion of “involuntary removal” projects as part of his detailed plan to end street homelessness, attempting to stray from the Housing First model. The fact that politicians are coming up with increasingly drastic measures to curb homelessness reflects the American public’s growing frustration with the issue. However, no matter how salient the frustration is, new ideas must draw from the lessons of the past to ensure their efficacy and safety. Instead of experimenting with completely new ideas like “involuntary removal,” it would be prudent to heed the lessons that the data tells us. A good first step would be to recognize that providing stable housing is, in fact, a solid foundation for policy, and renter-supportive policies should be enforced conjointly. There is no one way to resolve homelessness, so policymakers should continue to explore targeted approaches for different groups, which may lead to a smaller population of homeless people in the long run.