VANESSA THOMPSON – NOVEMBER 14TH, 2019 COPY-EDITOR: SHAWN SHIN

Wei Guo, an environmental and agricultural economist and researcher at the University of California, Berkeley, is currently investigating the value of natural landscapes and their property values. On October 25th, 2019, Guo was very generous to share her work and findings with BER Staff Writer, Vanessa Thompson, in the following interview:

Thompson: Hello, thank you so much for joining me today. I was hoping to talk about your research here at Cal. I know you are working in the Department of Agricultural Economics. What specific research projects are you currently working on?

Guo: Hi Vanessa. I would say I have broad research interests. However, my main research interest is in agricultural economics. Currently, I am working on two projects. One of them analyzes how land certified as critical habitats affect home prices surrounding the habitat. For example, an area will be deemed a critical habitat if endangered species are found on the land. After certifying it a critical habitat, the use of the land will become limited, restricting building and any harmful activities to the ecosystem. Because of the limited use of the land, the land value may decrease. However, properties around the critical habitat increase since having a protected natural area is desirable.

Thompson: What goes into determining if a property is more valuable when deemed a critical habitats?

Guo: The way of determining these values is through an econometric method called regression discontinuity. We look at the houses and land surrounding the border of the critical habitat. We assume that the land one kilometer from the boundary doesn’t have much difference from the value of the critical habitat. We look at the land near the boundary and then compare the value.

Thompson: Can you tell me more about how you use regression discontinuity?

Guo: Regression discontinuity is a method with the basic assumption that there is a discontinuity, and on both sides of the discontinuity, the data is fairly similar. With regression discontinuity, it should run smoothly, except for one significant jump. In our research, the big difference is the boundary of the critical habitat. So if there is no discontinuity, we shouldn’t see any large change in price. With this dataset, we do see a jump that we found significant.

Regression discontinuity is also a very popular method in economic research because it is very clean and intuitive. It is very easy to see a result just by cleaning the data and doing some descriptive analysis.*

Thompson: Regarding other work in this field, has there been much research investigating property values and critical habitat status, or is this relatively new in the field?

Guo: Well, in terms of this dataset, not really, but I am doing one other research project with this same dataset. The data is from Zillow, which is the largest real estate database. They gave us access to their dataset, and I am using it to also look at how political propensity affects the price. So in the most recent election, we expected a democratic win, but the Democratic party lost mainly because some key states swung red. Six states supported the Democratic Party in the previous election and also swung red in 2016. I want to look at the boundary of these states before and after the election and see if there are any changes of the home price.

Thompson: Will you be looking at state or local counties in terms of their politics and home values?

Guo: I am hoping to look at both, but start at the state level. Looking at the state level will take me maybe a month to analyze. I am planning to look at the country level, but that will be a future step to take.

Thompson: Why do you believe the politics would affect the home pricing?

Guo: There are many potential effects. One very obvious effect is that the Democratic and Republican parties have very different stances on property taxes. The Republican party strives for lower property taxes for high-income households as opposed to Democrats who push for lower taxes for low-income households. So if a state switches to vote for a different party, property owners may believe their property taxes will change. Second, people with strong political affiliations may want to move if their state votes for a party they do not support. So that is another possible issue that could change pricing.

Thompson: What about the recent phenomenon that wealthier urban individuals are Democratic and live in cities, whereas rural areas are now mainly Republican?

Guo: That is a good question, and this is why we look at the boundary between the two states. To address this, regression discontinuity becomes applicable once again. I assume near the edge of the property there will be a difference between wealth and other factors. This analysis will account for these differences.

Thompson: What about other political policies that may be influential? For example, could policies dictating the amount of welfare, the number of companies in the area, and government programs have an effect? How could those affect home pricing and where people want to live? Could other factors like how good a school district is also affect where people live and the demand for those homes? With the politics influencing those other economic factors, could that influence your results?

Guo: Right, that is why we are looking at the states and counties that swung to a new party. So there shouldn’t be a big difference. I am looking at the flipped states, in which there shouldn’t be a big difference. But all of this is preliminary, and we will address these as we investigate further.

What we have found so far is that before the election, the gap between the home price of the Democratic state neighbor and the swing state was small. After the election, the gap widened. This gap warrants further investigation. I speculate that the expectations on taxes and other policies changed, and may have influenced prices or influenced people to move to other states.

Thompson: This is a fascinating topic. Studying how we value properties that protect nature and how politics affects the price of our homes properties are really important to investigate. Thank you so much for your time and sharing your work with us.

Guo: Of course. Thank you!

*Editor’s Note: If you’d like to learn more about Regression Discontinuity, Wikipedia has a statistic-heavy introduction to the methodology.

Further Discussion by the interviewer:

Natural landscapes have profound effects on communities, including making people happier, less violent, and even more generous. Wei Guo, an environmental economist and researcher at the University of California, Berkeley, is currently investigating the value of natural landscapes and their property values when protected.

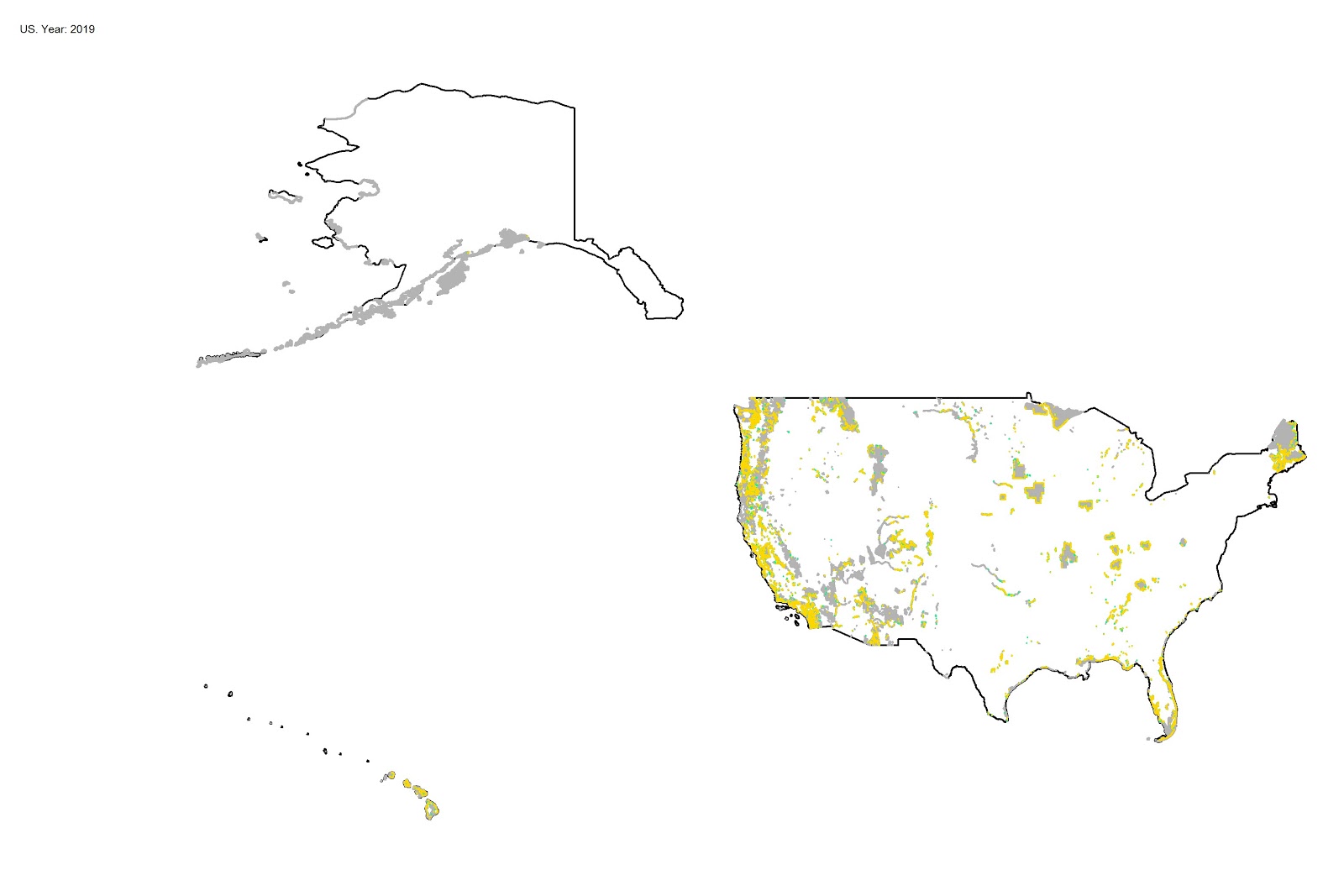

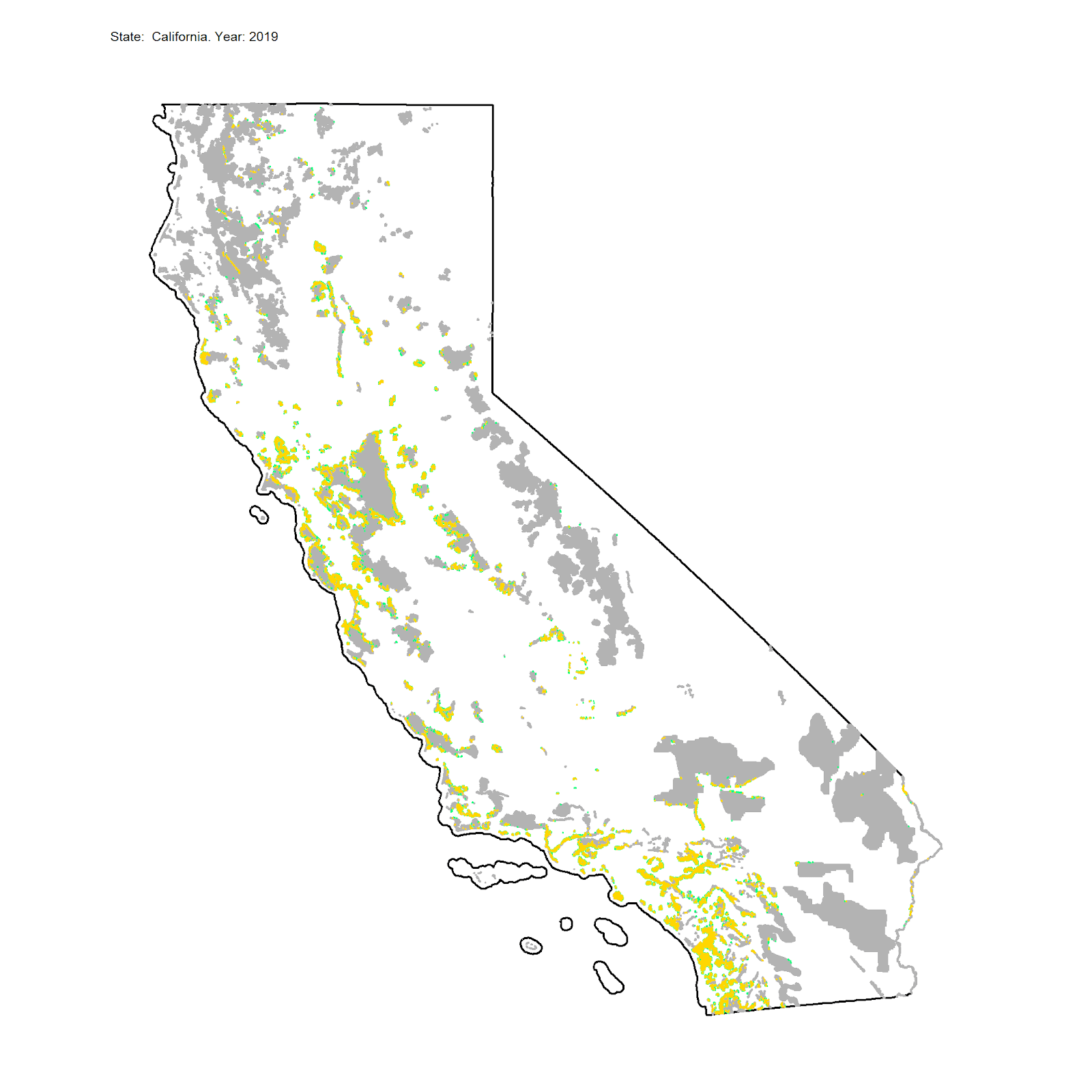

Guo’s work is significant due to the large number of critical habitats. Many properties have been declared as critical habitats, which protects and provides safe areas for 704 of the 1500 endangered species in the United States. Guo’s map below shows the number of properties surrounding critical habitats. The gold points show the land transactions located within 500 meters near the border of critical habitats, and the green points show the transactions within 1 kilometer. Guo’s work and the research of other environmental economists are vital to the understanding of how capital value plays a role in the protection of our natural spaces.

The figures below show the number of critical habitats in the United States and California. These show how many areas are deemed vital for ecosystem and species protection. Guo generated both using the Zillow dataset. We thank Guo Wei for generously sharing these visuals with us.

Featured Image: Berkeley

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.