HOWARD YAN – FEBRUARY 17TH, 2020 EDITOR: AMANDA YAO

Early Migration and Colonial Period

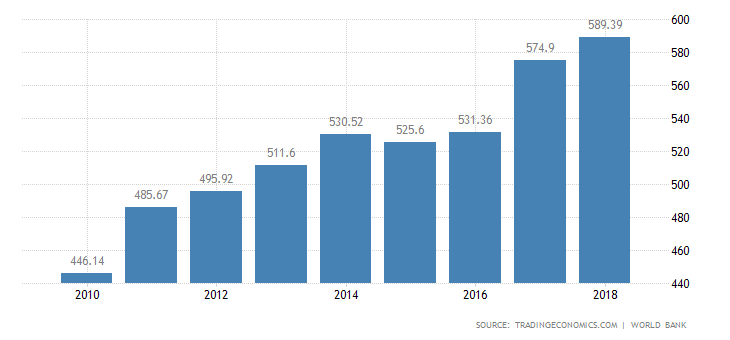

Situated to the east of mainland China, Taiwan occupies a strategic position among global supply chains. Appropriately dubbed an Asian Tiger, the island’s modern infrastructure, extensive foreign reserves, and $590 billion GDP have placed it in the top 25 of 185 economies globally. Backed by one of the world’s most advanced microchip sectors, it is recognized as a developed, high-income economy, a first for the Chinese-speaking world. Initially settled by Han immigrants during the Ming Dynasty, and subsequently conquered by the Qing, Taiwan has been a frequent destination of wealthy, educated Chinese seeking independence from the government in Beijing. However, the arriving Han immigrants also displaced indigenous tribes, forcing them to settle in areas less suitable for agriculture. Constant warfare also impoverished aboriginal peoples, whose average income is now less than half of the national average. Soon, immigrant arrivals overwhelmed native populations, placing Taiwan firmly under Chinese rule. Taiwan remained under Chinese rule until the Sino-Japanese War, when it was seceded to Japan under the Treaty of Shimonoseki. The Japanese administration effectively improved the island’s educational, health, and transportation infrastructure; however, most benefits were intended for Japanese immigrants, as evidenced by the island being denied representation in the Japanese government, and much of this progress was reversed during the Second World War.

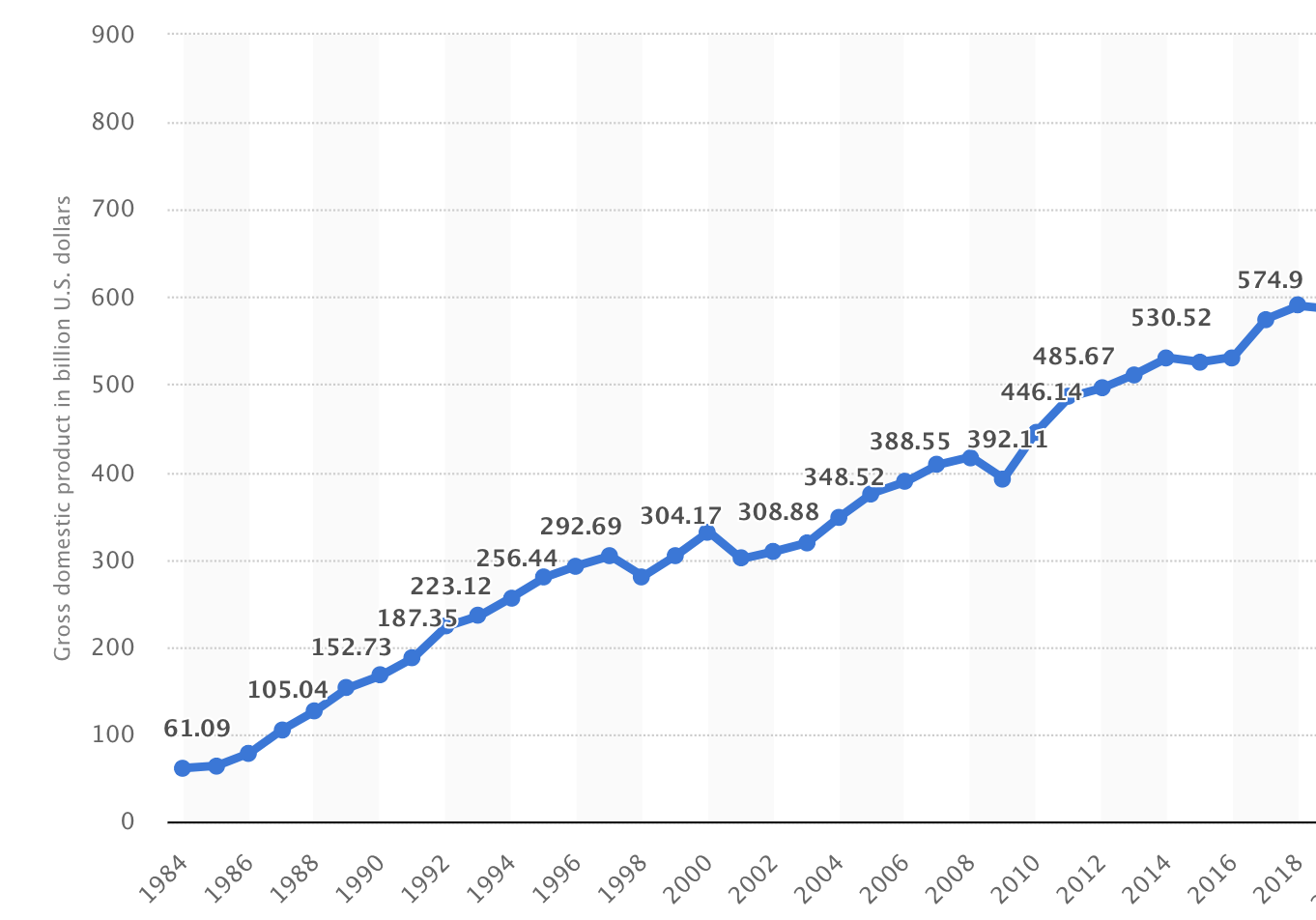

Taiwan GDP over Time (Billions of USD)

Source: World Bank

Modern Era

Dissatisfied by the loss of Taiwan, severe economic stagnation, and failed military campaigns against Western powers, the mainland Chinese consequently overthrew the Manchu Qing Dynasty, establishing the Republic of China in its place. Today, both the mainland and Taiwanese governments credit Dr. Sun Yat-Sen, widely considered to be the Father of Modern China, for this historic occasion. After achieving victory in World War II against Japan and the remaining Axis powers, but suffering a subsequent defeat in the Chinese Civil War, the Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party) fled the mainland for Taiwan. There, they re-established the Republic of China with its capital in Taipei, bringing with them much of China’s gold reserves and human capital. Having endured extensive wartime bombing and an influx of mainland immigrants, Taiwan was plagued with divisions between native and immigrant populations, weakened infrastructure, and a per-capita GDP comparable to that of the Congo. Hyperinflation was rampant, and a fatigued population was faced with the arduous task of re-development.

Asian Tiger Era and the Ten National Projects

Aware of Taiwan’s weak economic situation, the Taiwanese government launched a series of reform policies, initially focusing on curbing hyperinflation and stabilizing the Taiwanese dollar in the years immediately following 1945. The government then proceeded to redistribute land from the gentry to the lower classes. Doing so expanded Taiwan’s agricultural production, allowing the government to focus on improving education and industrial production. US economic aid subsidized industrial production costs, resulting in strong export growth. Drawn by low manufacturing costs, wages, and a relatively educated workforce Japanese companies began entering the Taiwanese market. Low interest rates on loans and government subsidies further boosted economic growth and large R&D investments developed the fledgling microchip industry. By the 1960s, annual real GDP growth averaged more than 10.3% and major companies, such as IBM, began sourcing chips and electronic components from the island.

By the 1970s, Premier Chiang Ching-Kuo’s Ten Major Construction Projects had built infrastructure across Taiwan, increased electricity production, and boosted steel production, critical components of the infrastructure-fueled boom. Costing over $10 billion in costs, the completion of Premier Ching-Kuo’s projects signaled Taiwan’s entry into the modern era. FDI inflows spiked, supporting investments such as the Hsinchu Technology Park and the expansion of family businesses, which form the backbone of the current economy. By the early 21st century, Taiwan’s GDP per capita had risen from $1400 immediately following World War II to more than $50,000 on purchasing power parity (PPP), higher than that of most developed European nations at the time. Though GDP per capita on a nominal basis remained at around $20,000, the economy appeared to be on solid footing.

Source: Trading Economics

Taiwan in the 21st Century

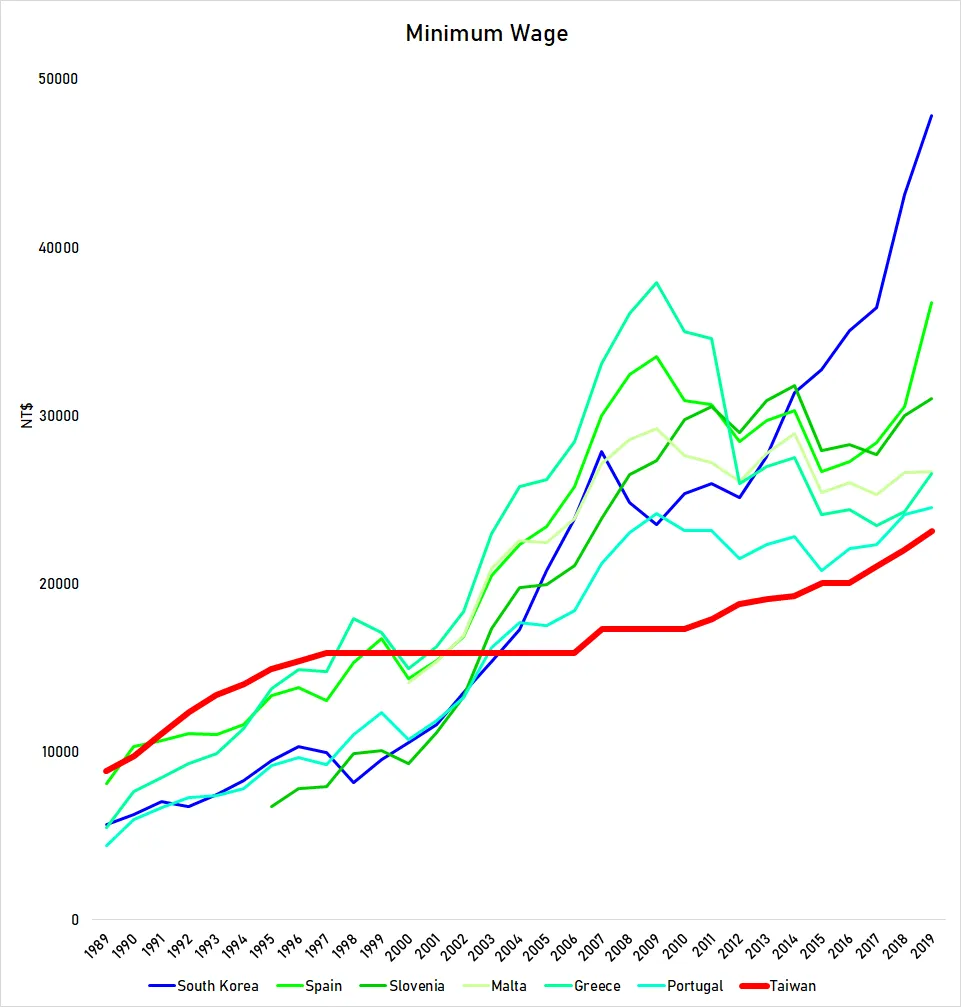

However, the export-dependent economic engine began to stagnate as mainland China opened special economic zones towards the mid-1980s, granting access to cheaper labor. Companies began relocating supply chains elsewhere to China and Southeast Asia, causing Taiwan’s GDP growth to drop. This emphasis on pursuing lower labor costs discouraged innovation while companies left Taiwan for Southeast Asia, due to the region’s relatively lower wages and abundant raw resources. Taiwan’s focus on family-sized businesses and inability to produce global brands, such as South Korea’s chaebol Samsung and LG Electronics, stunted its competitiveness. Furthermore, exclusion from multiple free trade agreements depressed exports, which account for a sizable portion of GDP. Consequently, wage growth has remained stagnant for nearly two decades. Despite producing one of the world’s most educated workforces, the government has failed to create jobs that fully harness college graduates’ know-how. The resulting brain drain of professionals was therefore hardly surprising.

Source: Ketagalan Media

Multiple China-friendly Kuomintang (KMT) administrations have vowed to bolster relationships with China, promoting higher trade volume and stronger tourism ties. However, a skeptical public rejected such measures, voting the independence-leaning Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) into power by 2016. To reduce dependence on China, Taiwan embarked on the New Southbound Policy to attract new investments and consumers in Southeast Asia. This policy appeared especially sound given that only a small percentage of Taiwan’s exports are covered by free trade agreements. Despite this, China continued to account for a sizable share of exports and diversification has been slow in this area.

General Outlook

Recent figures indicate economic growth at around 2.7% for 2019, a slight drop from 2018, but nevertheless an improvement from 0.8% in 2015. A recent bill which raised the monthly minimum wage by 3% and hourly minimum wage by 5% is expected to boost disposable income and consumption spending for fiscal year 2020. Businesses relocating to Taiwan to avoid tariffs from the US-China trade war are expected to temporarily create jobs and fuel investment spending. However, the possibility of further trade agreement phases between the US and China, in addition to lucrative opportunities in Vietnam, are likely to reverse such gains. Despite relatively decent performance, growth is hampered by trade tensions and future growth may decline if companies return to the mainland.

Featured Image Source: Location Scout

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.

2 thoughts on “Analysis of Taiwanese Economic History and Policies”