Author: Tucker Gauss | Editor: Mahlet Habteyes

Jogo bonito: the beautiful game. Soccer, when you’re a kid, is pure—harmless FIFA video games, lunchtime scrimmages, Sunday Premier League matches wearing your favorite team’s (overpriced yet still awesome) kit.

Then, you grow up. More specifically, you take a few economics classes and now see everything through that lens, and it quickly ruins the fun. Between club power inequalities, rapid quantification of player values, and brutal labor conditions, the modern soccer transfer market is closer to The Wolf of Wall Street than an innocent game. Safe to say, the economics of soccer are anything but beautiful.

Big Clubs Have All the Power

The most obvious parallel between European soccer and the American economic landscape? Inequality.

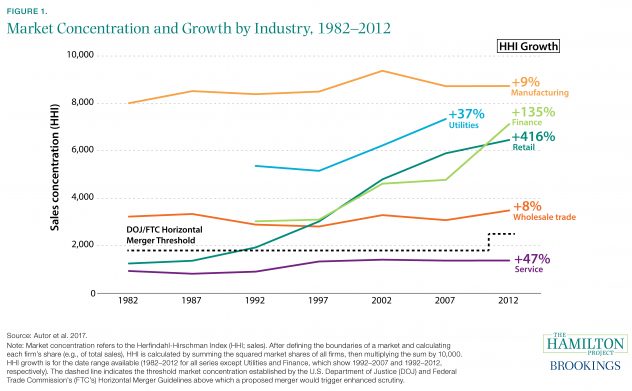

Club revenues, a common indicator of wealth in soccer, paint a dire picture. The 20 English Premier League clubs made a combined $5.84 billion in the 2017-18 season—more than the 617 teams in Europe’s 50 lower divisions. Market power concentration is a familiar story for the US economy, as the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (an indicator of market imbalance) grows (see: Figure 1).

Figure 1: Market Concentration and Growth by Industry, 1982-2012 by Brookings

The problem is self-perpetuating, too. Major clubs not only earn prize money from on-field success, but also profit from marketing, merchandise, TV deals, and brand sponsorships. As the game becomes more global, fans are less likely to support their local third-division club, instead funneling viewership, talent, and money into the pockets of major teams.

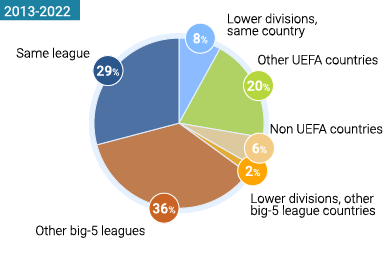

This widening gap is not only present within leagues but also between leagues. Booming investments from major clubs tend to benefit other major clubs, and specifically clubs in Europe’s top five divisions (England, Spain, Italy, France, Germany). In essence, money simply switches pockets from wealthy countries to wealthier countries (see: Figure 2). This cements inequality between countries, a trend mirrored by growing wealth gaps between developed countries and the rest of the world.

Figure 2: Recipients of Transfer Fees Paid by Big-5 Clubs by Football Observatory

These issues culminated in the European Super League, a proposal to form a separate division with each of Europe’s biggest clubs: Real Madrid, Barcelona, Manchester United, and more. Although the plan ultimately failed, the Super League demonstrates how big clubs prioritize their bottom line over history, fans, and economic parity. For close observers of corporate behavior in the US, that should ring a bell.

Numbers, Numbers, Numbers

As data becomes more accessible and complex, its stranglehold over the transfer market grows stronger. Commentators, fans, and clubs now regularly rely on advanced new metrics to determine player value. For instance, xG assesses the expected probability of scoring a goal from a certain situation or WhoScored match ratings as a holistic indicator of player performance. In the context of fan discourse, these “objective” statistics replaced personal, emotional discussions.

However, the implications for the transfer market are far more extreme. In lockstep with the rise of Jane Street and other quantitative trading firms, clubs view players as quantifiable commodities rather than human beings.

Need an example? Look no further than Dele Alli.

Once seen as the future of English soccer, Alli suffered poor form and injuries after his breakout season in 2016. His transfer value plummeted as a result—much to the delight of news outlets, who sensationally documented his collapse (see: Figure 3). Headlines like “From £40m, to £10m, to nothing!” demonstrate how quantifiable player values are a weapon for journalists.

Figure 3: by Premier League Market Value Update by 22BET

Little did these journalists know that Alli’s problems were far greater off the pitch. In an interview last year, the former Tottenham star revealed that he experienced sexual abuse as a child. While recovering from his trauma, Alli also faced the pressure of performing under the scrutiny of millions of fans. His quantifiable “value” fluctuated with each game, each touch of the ball, leaving no room for error. Any misstep could ax him from financial security and his home at a moment’s notice. Without any recognition of Alli’s traumatic experiences, Everton blindly followed the data of player valuation and released him from his contract in 2024.

Growing allegiance to data has some advantages, like reducing nationalistic or ethnic biases from scouting. However, data often ignores the context of a match or each players’ role. Each individual touch, movement, and pass can flip a game on its head, so statistics alone do not always represent who truly had the biggest influence on a game. Similarly, quantitative financial trading or data-based economic shifts return enormous profits but lack reliable methods to address social and political concerns—from privacy regulations to human well-being. For both European soccer and the economy, data metrics may miss the trees for the forest.

Too Many Games

Players play too many games, plain and simple. As the game becomes faster and more physical, expanded formats for the Champions League, Europa League, and World Cup—soccer’s premier competitions— have added even more minutes to an already packed calendar. The result? A 15% increase in injuries in the 2023-24 season.

Manchester City midfielder Rodri led the outcry against the uptick in match time, even warning that players would strike in protest. You can probably guess what happened next: he suffered a season-ending hamstring injury during a match the following week.

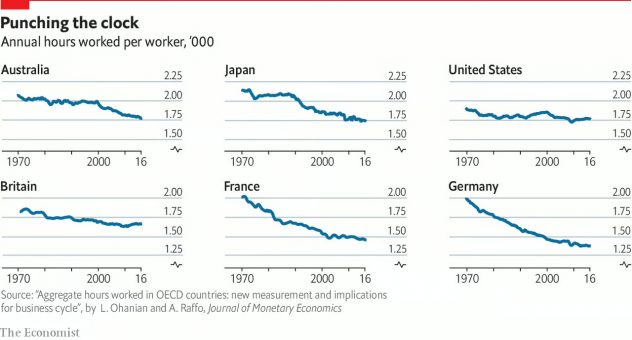

This closely mirrors the intense demands placed on workers in the US. While labor hours have declined in most developed nations, American workers have been left behind. Since 2000, average hours in the U.S. have plateaued or even risen (see: Figure 4). Recall the recent death of 35-year-old investment banker Leo Lukenas after working 100-hour weeks, and the situation seems all the more dire.

Figure 4: Annual Hours Worked per Worker in the Year 2000 by The Economist

Progress, Maybe?

While the future of European soccer and the US economy seem bleak, recent events have been promising. In the past year, the Federal Trade Commission stepped up efforts to break up Google and ban non-compete clauses, allowing employees to seek better pay and working conditions at rival companies. Taking notes from US regulators, Premier League clubs voted to strengthen Financial Fair Play (FFP) rules by limiting the spread of a player’s transfer fee to five years. For context, this helps enforce FFP guidelines that limit deficit spending from major clubs to $137 million. While imperfect in practice, FFP levels the playing field by ensuring clubs cannot spend their way to success.

This push could allow for mid-tier clubs to benefit from reduced financial inequality. With stricter FFP enforcement, there is potential for more competitive leagues, enabling smaller clubs to challenge traditional powerhouses. This initiative also shows that regulatory bodies are willing to address inequalities and provide a framework for more economic equality.

Labor rights may improve, too. Player power, or a player’s influence in contract negotiations and transfer deals, continues to rise since Neymar’s shocking departure from Barcelona in 2017. Neymar’s world-record fee of over $200 million completely reshaped the transfer market, as clubs began to negotiate more directly with players. Further, the European Union Court of Justice declared that European soccer contracts violated free labor movement rights. Currently, both a player’s old and new club must compensate them for a terminated contract. This poses a clear burden to clubs hoping to sign a new player, and its reversal in the EU courts reflects a growing shift towards player rights.

Next time you turn on El Clasico or a World Cup match, watch closely. The most important competition isn’t between Real Madrid and Barcelona, or Team A and Team B. Rather, it’s off the pitch: it’s the struggle between economic freedoms and an unequal, unfair soccer economy.

Featured Image by Buzzfeed News