Writer: Teddy Kuser, Editor: Yubeen Hyun

What is the first thing that comes to mind when you think of the Netherlands? Windmills? Bicycles? Stroopwafels? Well, if you’ve ever been lucky enough to take a flight over the country’s vast vibrant fields, you might think of the tulip.

In the 17th century, a unique market developed in the Dutch United Provinces. Unlike most European nations at the time, this was not one of fish, timber, furs, grains, or spices. What distinguished the tulip market from any other in Europe was that the tulips themselves held no intrinsic value. Yet somehow, the price of a single tulip bulb managed to soar far beyond the rarest of precious metals. By February 5th, 1637, a single bulb could be purchased for as much as a modern-day equivalent of 750,000 USD. This marked the first significant financial bubble in written history, whose legacy reaches far beyond a cautionary tale of investing in speculative markets. “Tulipmania” was the root of modern investing, and understanding how the tulip market developed, soared, and crashed can help explain how contemporary capitalism functions and why it came to be. (CFI)

A key factor in the rise of this baseless tulip market was the burgeoning Dutch middle class. Following the fall of Antwerp during the 80 Years War, scores of Calvinist merchants fled to the Protestant Dutch Netherlands, and the likes of artisans, merchants, and those of various skilled professions became the majority in Dutch society. This new middle class wisely put their disposable income to work at the onset of the 17th century by purchasing shares in joint stock company ventures. Shares in these companies eliminated a great deal of the risk generally associated with funding a trade expedition that a single wealthy patron would otherwise finance. Joint-stock companies sold shares affordable to most members of the growing middle class, allowing all investors to assume limited liability (risk was limited to the amount they invested in the company as opposed to the entire venture). The sale of shares provided capital for companies to reinvest in their ventures and far less volatile returns for those who bought them.

Nevertheless, investors eventually sought an even “safer” investment. Something that perhaps couldn’t sink at sea, something exotic, something to visually display their great wealth – a far more conspicuous and speculative investment from a revisionist lens. In retrospect, the tulip, of course, was not a “safe” investment, but how could the Dutch have known? A market of this kind was unprecedented. The Dutch believed the flower held value in its extraordinary beauty and rarity and demonstrated their admiration by investing fortunes from textiles and trade into various bulbs that would hopefully bloom in extravagant colors and patterns.

The crown jewel of the inflated tulip market was a variety known as the Semper Augustus. Even its name, which it owed to the ancient Roman emperor Caesar Augustus, signified royalty and extravagant wealth. Distinguishable by its vibrant red and white stripes, the Semper was among the most recognizable tulip varieties. But, what made it so valuable was its rarity. Through a process known as “breaking,” florists intentionally infected bulbs with a floral disease known to mark tulips with unusual patterns and colors. However, this practice came with the risk that the bulb would never bloom, making these new artificial tulip varieties all the more valuable. But no matter how rare or vibrant any variety might be, the intrinsic worth of a single bulb was never comparable to a brewery, a small farm, or the most grandiose of manors. And yet, a single Semper could easily purchase any of these properties. Why on Earth was this the case? (Mike Dash, Tulipomania)

It all boils down to behavioral psychology, particularly the Greater Fool Theory, which states that an inflated financial market is entirely driven by speculative greed. Everyone believes they can find some “greater fool” who will buy their intrinsically worthless asset from them. Just like in a game of hot potato, floral speculators passed their tulip bulbs from one fool to the next, hoping they could find another buyer before the music stopped. But, in the end, someone was always left with the flaming potato in hand, and during tulip mania, that meant instant bankruptcy. Game over. Economists call the pause in the music the mean reversion. Eventually, crazy high prices return to Earth, and markets correct themselves. A mean reversion is inevitable when the growth of an asset’s price outpaces the growth of its value. Unfortunately, unlike a tech company in Silicon Valley, a tulip is intrinsically worthless, which was reflected in the market’s reversion.

Furthermore, the mindless submission of the middle class to the elitist practice of purchasing and trading tulip bulbs also reflects a herd mentality. A modern example of this phenomenon is the regular rush to purchase the new iPhone when it is released. Everyone NEEDS the latest model, or at least one without the embarrassingly antiquated home button. Why? Because everyone else has or wants it, and people tend to catch a bad case of FOMO when everyone else is doing something they aren’t. When aristocrats began purchasing the novel flower from the Eastern Ottoman Empire, middle-class merchants, and skilled artisans were led to believe they had to buy bulbs or face alienation from the Dutch elite. Extreme speculators sold their land or mortgaged homes to raise the necessary guilders to purchase a bulb. While some amassed great fortunes, most were left penniless (or guilderless).

Beyond the behavioral frenzy, the economic climate of the Dutch Netherlands and the development of a critical financial instrument helped facilitate the tulip mania. The Ace, as referred to by the Dutch, was a legally binding contract that designated the sale of a tulip for a later date. People were not just buying existing tulips; they were buying in hopes that they would get one. At the height of the mania, bulbs were hardly sold directly to their buyers. Most often, Aces were exchanged not by floral connoisseurs but by speculators seeking a profit. Like mortgages in 2008, Aces were issued with no margin requirement. In most future markets, buyers must pay a percentage of the contract upfront as a safety net, but in the United Provinces, anyone with a pulse could buy an Ace. The tulip essentially became the cryptocurrency of its time – volatile and baseless. Eventually, the market reoriented in such a fashion that it resembled a modern stock exchange. Each tulip variety had a dynamic price attached to it. The Semper Augustus was the blue-chip stock of the mania and soared off the charts at a peak value of 5,200 guilders (the modern-day equivalent of $750,000). To fan the flames of the fever pitch tulip mania, interest rates in the Netherlands dropped steeply (in other words, money was cheap). Now, it was possible to trade tulip futures without any margin. With guilders flooding the economy and the relative availability of the Ace, prices soared. However, the mania incentivized the mass cultivation of tulips throughout Europe, and supply steadily rose as demand began to decline. (Mike Dash, Tulipomania)

Eventually, doubts crept in, and the seemingly unwavering confidence in the market began to wane. Suddenly, a cascade of contract sales struck the market. Desperate tulip merchants rushed to cash in on their Aces with no buyers to be found. A domino effect ensued, and the Netherlands fell into an economic crisis. Like a house of cards, a beauty from afar but bound to collapse, the tulip market began its implosion on February 3rd, 1637. By February 9th, the market had lost one-third of its value, and by May 1st, tulips were utterly worthless. (CFI).

So, we know how and why the tulip market rose and collapsed, but what was its immediate and lasting impact on the Dutch economy? Initially, many members of the largest middle class in Europe went bankrupt. Although equally invested in the tulip market, the aristocracy had a much softer landing due to their more diversified assets. Many members of the upper-class elite had a significant portion of their wealth tied to land. By comparison, the middle class mostly worked for wages and lived in densely populated cities on plots barely large enough for their homes. After many of them mortgaged what little property they owned to play the market, the crash left them with nothing to fall back on.

Rightfully fearing a complete economic collapse, the Dutch government intervened in the final months of 1637. The issue with futures has been and always will be that if a market crashes, all of a sudden, you are not getting what you paid for at a discount but rather a devastating premium. The government sought to eliminate the avalanche of debt that crashed down on members of the middle class who, in some cases, owed tens of thousands in guilders to aristocrats. By eliminating a legal penalty for failing to fulfill contracts, the hope was that middle-class speculators could focus on repaying their bank loans (the ones they snatched at low interest rates). The plan worked, and the middle class continued to expand and prosper over the next few decades. This success posed the question of whether the government playing an interventionist role in economic affairs would always be beneficial. While it may have worked for a short period, what about Holland’s long-term financial stability? The country had achieved its dominance in foreign trade and shipping through a free market system. Was this the beginning of the end? Quite the contrary. Government intervention in Holland during the 1720s softened the impact of the South Sea Bubble, a catastrophic joint-stock financial crisis that briefly devastated the British economy. Regulations were imposed that prevented the monopolization of any single joint stock company, incentivizing investors to diversify their portfolios. By comparison, England’s South Sea company held a government-sanctioned monopoly on all trade with South America and, therefore, was the sole investment in many British portfolios.

A surface-level analysis tells us that Tulipomania was a speculative disaster and a classic example of a financial bubble. However, this wild financial phenomenon was more than meets the eye. We know Amsterdam was a bustling bastion of European and global trade. One of the unintended consequences of globalization was a heterogeneous circulation of currencies. Coins from many countries were inefficiently exchanged and traded in Dutch markets. Some currencies, such as Charles V’s Reichsthaler, were intentionally debased (the precious metal contents of the coins were decreased) but maintained face value. With a diverse array of currencies flowing through the market and fluctuating exchange rates unique to each coin, making everyday transactions was like trying to build a house on shifting sand.

Within a sea of uncertainty, arose a pillar of trust and stability: the Bank of Amsterdam. A central bank allowed Dutch citizens to trade their various currencies for bank money, a universal credit in the Netherlands. Bank money was so valuable that it was traded at a premium, or Agio, as the Dutch called it. Although bank money helped revitalize the economy, it also led to a sharp spike in inflation. In an instant, the money supply more than quadrupled. The resulting inflation impacted the price of all goods, including tulips. While behavioral aspects of the frenzy undoubtedly resembled those of modern financial bubbles, inflation unquestionably accounted for a sizable share of the tulip’s valuation.

So, tulip price hikes could largely be attributed to inflation. Why, then, is the mania remembered as a classic financial bubble that skyrocketed in value solely due to an irrational frenzy of get-rich-quick schemes? Look no further than Calvinists. Dutch Calvinists despised the conspicuous culture that consumed the Netherlands at the height of its prosperity in the Golden Age. The extravagant displays of wealth amongst the aristocracy directly violated a core tenet of their faith: frugality. To instill fear and bring an end to conspicuous consumption, Calvinists spread arguably false propaganda of a baseless tulip market. In a modern-day equivalent of going viral, this narrative induced the panic of contract sales that ensued.

Whether fact or fiction, much can still be gleaned from the psychological frenzy of Tulipmania. It serves as a warning about the dangers of speculative investments and is an important example of the advantages of government intervention, even in a capitalist economy. The irrational exuberance that fueled the tulip market is mirrored in contemporary financial crises, from stock market crashes to housing bubbles. Ultimately, the tulip market’s legacy isn’t just the crash of a flower’s value, but the forces shaping financial markets and the importance of economic oversight.

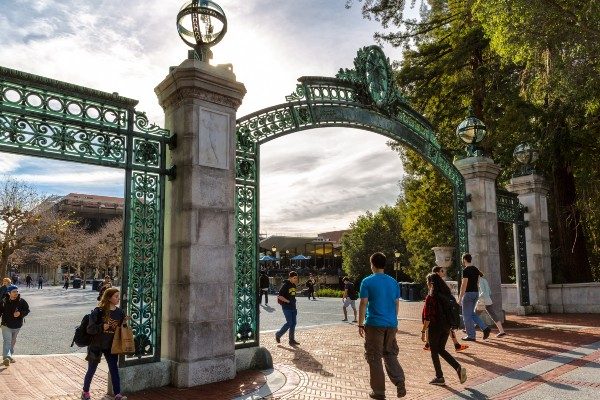

Featured image The Tulip Folly by Jean-Léon Gérôme