Writer: Sofia Belhouari | Editor: Rachel (Xiyue) Qin

California, the golden goose of U.S. agriculture, produces over a third of the country’s vegetables and two-thirds of its fruits and nuts. While that sounds like bragging rights, the numbers start to sour when you compare what California exports against what it costs locals to buy the same produce. Spoiler alert: Californians are paying significantly more for food than the countries to which California ships its goods.

The Global Produce Playground

In 2023 alone, California exported agricultural products worth over $20 billion, including staples such as almonds, pistachios, wine, and citrus fruits to over 150 countries. The top destinations? Japan, Canada, and the European Union, accounting for a combined $6 billion. Almonds alone made up a whopping $5 billion in exports, with pistachios close behind at $3.5 billion.

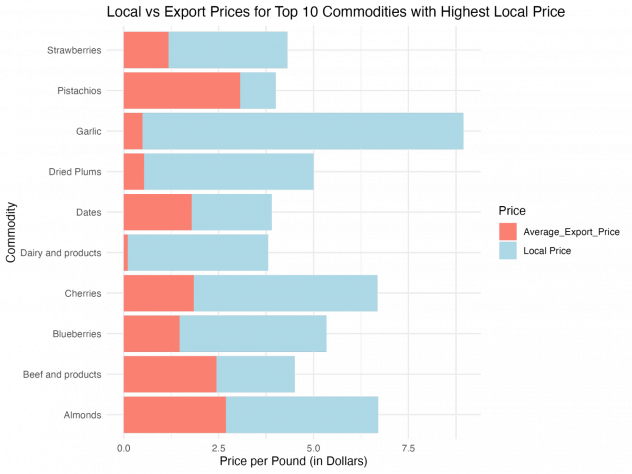

The pricing disparity becomes even clearer when you look at global markets. For instance, in Tokyo, a pound of California table grapes can sell for $2.50, while in Fresno—just miles from where they’re grown—the same grapes cost closer to $4.50 per pound. Similarly, almonds, a major export, retail in bulk overseas at $1.50 per pound while Californians pay nearly twice that in local stores.

Figure 1: Local vs. Export Prices for the Top 10 Commodities with the Highest Local Price

Methodology, or how to go beyond the glaring lack of transparency

Methodologically speaking, pulling together the data for this analysis was both a necessary evil and a lesson in California’s surprising lack of transparency when it comes to its agricultural economy. I began by sourcing raw data from UC Davis’s California export database—a promising start, albeit requiring manual adjustments to make the information usable. With a combination of R programming wizardry and sheer patience, I cleaned and merged the datasets to calculate essential variables like total exports, export ratios, and production quantities for key commodities. This meticulous cleaning process was necessary to uncover patterns buried under inconsistent formatting and incomplete data.

Yet, as thorough as the database might seem at first glance, it provided little to no insight into local consumer prices—a glaring omission given the state’s emphasis on its agricultural dominance. This forced me to take matters into my own hands. By cross-referencing pricing information from Whole Foods, Target, and the USDA, I assembled a dataset of local prices for California’s most iconic produce, from almonds to strawberries. It wasn’t glamorous, but it allowed me to visualize the economic dissonance between what California grows, what it exports, and what it charges its own residents.

The resulting visualizations speak volumes. They depict stark price disparities and reveal a startling conclusion: regression analysis isn’t even necessary to prove that exports may not be the panacea they’re touted to be. California’s agricultural strategy, heavily weighted toward exports, prioritizes global markets at the expense of local affordability. And for a state that prides itself on being the “breadbasket of the nation,” the lack of readily available, transparent information on local versus export market dynamics is not just inconvenient—it’s telling. This absence underscores a deeper systemic issue: the export-first mentality has led to blind spots in understanding how to balance global economic goals with local needs.

The Economics of (Not) Eating Local

Here’s the kicker: California’s produce economy operates like a tragicomic paradox. The state exports food at globally competitive prices while locals are priced out of their own crops. Sure, exporting brings billions into the economy, but the question is, at what cost to Californians? Affordable, nutritious food shouldn’t feel like a luxury item in the very state that grows it.

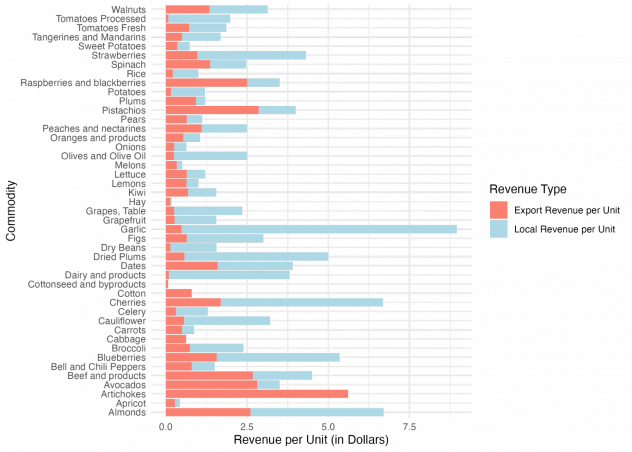

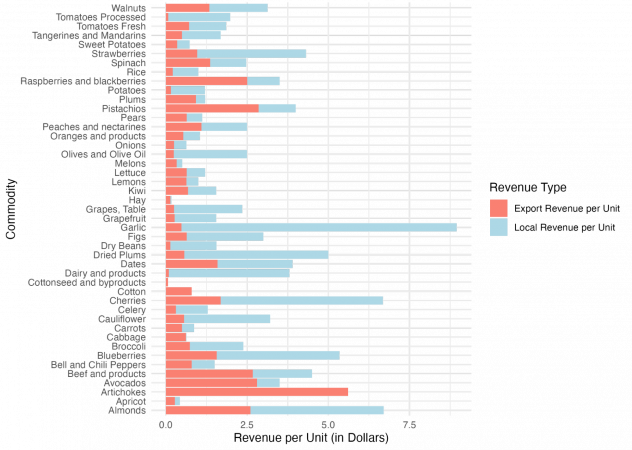

In our analysis, we took a closer look at this paradox by calculating export revenue per unit and comparing it to the potential local revenue per unit if California were to sell all its exported produce within the state. To do this, we normalized the revenue calculations to ensure fair comparisons. Export revenue per unit was derived by dividing the total export value by the quantity exported, reflecting the average price received in foreign markets. Similarly, local revenue per unit was based on local prices and the same exported quantities. The results were fascinating, to say the least: California could generate higher revenue by selling its exported quantities locally, assuming all else remains equal.

Figure 2: Comparison of Local Revenue vs. Export Revenue per Unit (2018)

Figure 3: Comparison of Local Revenue vs. Export Revenue per Unit (2019)

This isn’t just theoretical math; it’s a glaring economic contradiction. If local revenue per unit consistently beats export revenue, why does California persist in its export-heavy strategy? The numbers suggest that exporting isn’t about maximizing revenue but is likely driven by exogenous factors—think trade agreements, international demand, or the prestige of dominating global markets. There’s a structural bias at play here, prioritizing international markets even when local sales could be more profitable and, critically, more equitable for Californians.

Why Are We Here?

Blame it on the system—or several overlapping systems. Here’s a short list of contributing factors:

- Land Costs: California’s agricultural land costs are some of the highest in the country, driving up the baseline price of everything grown here. The average price of irrigated cropland in California? $15,880 per acre, compared to a national average of $5,570.

- Water Wars: In drought-prone California, water isn’t just scarce—it’s also expensive. Farmers paid up to $1,200 per acre-foot of water in 2022, a 40% increase from 2017. Those costs trickle down to consumers.

- Export Priorities: California agriculture is an export-first business, with farmers chasing higher profit margins abroad. In 2022, California’s agricultural exports totaled 23.6 billion, leaving less supply for the local market.

Yet, as our analysis revealed, this export-driven strategy doesn’t always translate into higher revenues. Instead, it exacerbates local affordability issues. The system essentially exports not just produce but also affordability, leaving Californians to deal with higher grocery bills while the state caters to global appetites. If there’s one takeaway, it’s this: California’s agricultural priorities may need a hard reset—one that reexamines whether exporting prosperity is worth the cost of local scarcity.

Why This Matters

California isn’t just exporting its produce; it’s exporting affordability. While Japan gets cheaper grapes, low-income Californians are left choosing between rent and fresh food. This disparity isn’t just frustrating—it’s a failure of policy.

For perspective, consider this: the average Californian spends 15% of their income on food, while consumers in Japan or Canada spend just 10%. Those numbers hit even harder for low-income households, where food can consume up to 35% of monthly budgets.

What’s the Fix?

Let’s not sugarcoat this: fixing the system isn’t easy, but it isn’t impossible, either. Here’s where policy could step in:

- Subsidize for the Locals: Offer state-level subsidies to ensure Californians get access to affordable produce.

- Encourage Local Sales: Create incentives for farmers to sell more goods within the state at reduced costs. Think tax breaks, grants, or partnerships with local co-ops.

- Price Transparency: Require better reporting on how prices are set domestically vs. internationally. Knowledge is power, and Californians deserve to know why their grocery bills keep climbing.

Let’s take a step back: a short reflection on the limitations of this study

While it’s pertinent to assume that all exported commodities do not necessarily have to be exported, one has to acknowledge that Californian production greatly exceeds the local demand. Through our study and analysis, we’ve run the assumption that all production, if sold locally, would be sold at the same local price in all Californian markets – ambitious, but improbable.

These results should be taken with a grain of salt, and while this article is consumer-focused, a larger more holistic approach should be considered. Producers, especially smaller ones, tend to benefit from exports as government subsidies tend to favor such exchanges. Moreover, exchange rates valorize the US dollar, making US-issued commodities more valuable on the international market. Finally, local consumers are not necessarily the target demographic of certain production, and exporting gives the opportunity to producers to choose markets where their commodities are overvalued.

All in all, while over-exportations are one of the factors to blame for the rise of local prices, it would be dishonest to reduce all exogenous dynamics to that. As is always the case, a socially optimal equilibrium is required.

Closing Thoughts: California’s Double Standard

California’s agricultural export dominance is impressive, but it’s hard to celebrate when the locals footing the bill can’t afford to eat the fruit of their labor—literally. Balancing exports with in-state equity shouldn’t just be a dream; it should be the standard. Because when your biggest export is prosperity, it’s about time you shared some at home.

Featured image by Steven Weeks on Unsplash.