Writer: Gianna De Mayo | Editor: Ramya Sridhar

America: a nation whose promise of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness transformed it into more of an idea than a country. It’s the “greatest country in the world,” home to some of the most revolutionary scientific discoveries, technological advancements, and medical innovations… that only a small portion of people have the wealth to utilize. Embracing its demographical breadth, America implemented an affordable healthcare system able to assist every one of its citizens… that many don’t qualify for. In his Lyceum Address, Abraham Lincoln stated, “If destruction be our lot, we must ourselves be its author and finisher.” Almost 200 years later, American citizens face declining life expectancies, and requesting itemized medical bills to avoid being taken advantage of has become a trend on social media. Youth avoid emergency services corresponding to a new internal debate: the debt that comes with needing care or dying, which is more terrifying? The downfalls of the United States healthcare system and the destruction it does to the nation’s promised values is a demise of its own design.

Defining a ‘Fruit’-ful System

Nothing is ever perfect in practice, so critiques of American policies and expenditures are regularly dismissed as mere collective pessimism. The issue of comparing apples to oranges impedes progression in U.S. healthcare for a simple reason: it’s easiest to insist that something is the best option when refusing to acknowledge the potential value of any alternative. Building a comprehensive global perspective through comparison to countries that boast robust healthcare infrastructures may reveal what makes the U.S. system’s current state uniquely flawed.

The nature of a system can be somewhat eluded to by the nature of its comprising markets, and health insurance is an influential one. Universal healthcare can be categorized into three main formats: public, mandated, and mixed. In the U.S., “universal healthcare” typically refers to single-payer, tax-funded public systems (exemplified by the UK, Canada, Denmark, Spain, and Italy) designed to minimize or eliminate out-of-pocket costs. Mandated systems, funded predominantly by premiums, require citizens to be insured but offer flexible options for doing so, leading nations’ implementations to vary in offerings and funding sources. For instance, South Korea, Japan, and Germany finance their systems through joint employer and employee contributions, with the first two also benefiting from government subsidies. South Korea’s National Health Insurance exclusively offers public coverage, contrasting Switzerland’s heavily regulated private model with income-based subsidies. Germany provides choices between private insurance and public statutory funds, while Japan integrates its public and private options within employer- and location-based plans. In mixed systems, like those in Australia, Austria, Belgium, and France, universal public insurance is complemented by private sector involvement in providing supplemental coverage. Each system focuses on preventive care and health promotion while providing comprehensive coverage to all, resulting in lower costs and better outcomes.

The U.S. is entirely alone among major developed countries, its healthcare system functioning like a business, relying primarily on private insurance companies in a free market. While the government does provide coverage to certain groups (such as elderly and low-income individuals), the majority of Americans rely on private health insurance plans, which can be expensive and may not cover all necessary medical services. Alongside the lack of universal healthcare coverage, fragmentation with multiple payers and providers leads to waste and disparity. Other developed countries with universal healthcare often have more coordinated care delivery. Every operation of U.S. healthcare, from inefficient expenditure and price of care to the insurance and drug markets, undermines inalienable rights and places profits above patient welfare. At some point in the nation’s history, founding principles that drove America’s rise to economic greatness began overshadowing those without direct monetary benefit, like viewing medical care as a right rather than a normal good. For the future of a system responsible for hundreds of millions of lives, it’s critical for the nation to find an ethical balance between its values.

The Cost of an Onion

Figure 1: The contributions of government-funded programs and household out-of-pocket costs to the overall healthcare expenditure per capita in different developed nations (Austria, Canada, Denmark, France, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States). Purchasing power parity adjusts unit values for exchange rates between currencies as well as their worth, relative to the nation’s price level.

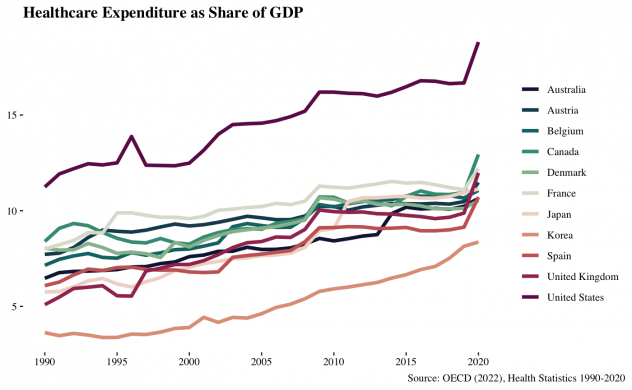

Figure 2

Throughout recent history, U.S. healthcare expenditure has far exceeded that of other countries and now accounts for almost 20% of the nation’s GDP. As seen in Figure 1, citizens’ out-of-pocket spending is somewhat comparable, but government per capita spending is more than twice that of other nations. Much of this spending goes towards administrative costs, weighted by the overcomplex system structure. While administrative costs are inevitable for any large system, spending typically decreases with innovation and the introduction of technological advancements. Digitization of records and automation typically leads to more efficient processing and, thus, lower necessary expenditure. Yet, due to the increasing complexity of the U.S. administrative system, the opposite effect is observed. Much like many of the nation’s other systems, U.S. healthcare is highly fragmented, with many providers, payers, and regulatory agencies involved. The resulting discontinuity can make it difficult for patients to navigate the system and for providers to coordinate care. Containing tiers of providers, countless regulations, and multilevel administration, the structure of U.S. healthcare is akin to an onion, with each layer committing its own form of daylight robbery.

A study by Nikhil Sahni (2021) estimated administrative costs account for approximately 25–30% of total national healthcare expenditure. Of 2019’s $3.8 trillion in expenses, $265 billion is considered waste, unnecessary spending that could be eliminated through intervention techniques limiting complex administration. In differentiating necessary spending from waste, money must be followed through various hand-offs in a traditionally untransparent process. Payers convey the medical necessity of a procedure through medical examinations and consultations before authorizing care services from physicians. Physicians must then submit claims to insurance companies or other payers to receive approval for coverage. These payers review the claims and contact providers with either approval or rejection. This process continues until a conclusion is reached and care is either provided or forgone. As a predominantly for-profit healthcare system, the U.S. sees costs incurred in each stage far higher than almost all other nations. In total, only approximately 26% of administrative spending is for functions related to active patient care. A 2021 analysis published by McKinsey proposed thirty system reform approaches revolving around streamlining and automation. Limiting administrative costs is not only possible, but is the first step to increasing efficiency in the U.S. healthcare system. Peeling back layers of the onion to optimize practices and expenditures means patients receive medical care faster without as many costs being passed on to them.

Insurance

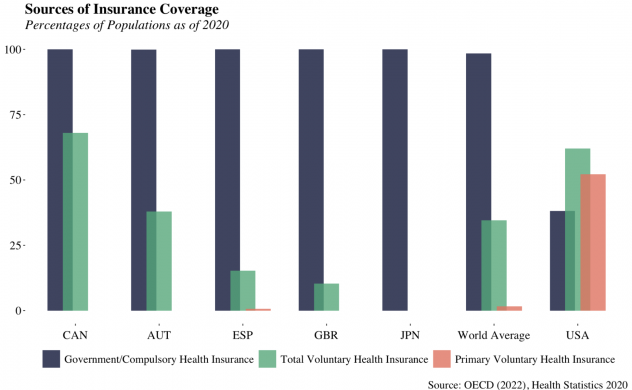

Figure 3

The U.S. is the only developed nation without guaranteed health coverage or any form of a free, publicly funded option, the only developed nation without a negotiating system for national drug prices, and the only developed nation whose government has no regulatory role in the insurance market. The U.S. population has 60.28% less access to Government-provided healthcare than the worldwide average. America and Chile are the only countries in the world where more than 0.7% of the population relies on voluntary health insurance as their primary source of coverage; America exceeds this standard by 51.5%. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 aimed to append some of these downfalls by requiring federal price negotiations for certain drugs covered by Medicare and limiting cost sharing. However, it neglected the fact that only 18% of Americans qualify for the program. The act opened the door to future (stronger) price regulations, but it alone can not offset the current manipulation of markets. Over time, the health insurance market became oligopolistic due to a combination of factors, including mergers and acquisitions among insurance companies, the high cost of entry into the market, and regulatory barriers. In a market competition study, the American Medical Association found that across all markets (PPO, HMO, POS, and Exchange), the two largest insurers held above 50% of the combined market share in all but eight states and territories. On a national level, the four-firm ratio of insurance companies is 48%. It increases to 65% when evaluating only Medicare markets, indicating the oligopoly’s significant control over the market. State and national regulation of the health insurance industry effectively posed barriers to entry for any competition while allowing freedom to set rates and coverage levels once in the market.

With ongoing healthcare overhaul, this oligopoly is growing more established in its ability to lower the quality of service and coverage, raise premiums, and limit patients’ choice of providers. This February, the Department of Justice admitted its failure to enforce antitrust laws, withdrawing three long-standing healthcare policy statements for being “overly permissive.” A case-by-case enforcement approach may remove the “safety zones” industry participants have utilized to make their actions narrowly permissible, but only time will tell if it can reintroduce competition to the market. In America, providers are paid on a fee-for-service model based on the number of services provided rather than the quality of care delivered. This can incentivize overuse and unnecessary procedures, leading to higher costs and potentially harmful outcomes. Insurers began requiring prior authorization initially to limit the amount of these procedures. However, with 4 in 5 physicians reporting abandonment of recommended treatments as a result, PA has become a tool for providers to reap a profit from undermining the efficiency of care. It may prove difficult to limit the power of entities who have gained almost complete control over a nation’s core systems — deciding who receives care, who doesn’t, when, and at what cost.

Outcomes

Roughly 30 million Americans remain uninsured, more than 100 million lack a primary care physician, and 114 million struggle to afford the healthcare they do receive. Of cost-desperate adults, 50% reported cutting back on food in the past 12 months to pay for medical care, and 14% have a friend or family member who has died in the last year due to an inability to pay for treatment. The lack of universal healthcare creates uneven access to care in rural or low-income areas, disproportionately impacting already marginalized and disadvantaged communities. Due to insurance prior authorization, a staggering 94% of physicians report regular significant delays in access to necessary care, with 33% recording instances where the process led to a severe adverse event involving life-threatening hospitalization or death of a patient. These statistics represent the most significant failures of the U.S. healthcare system reflected in patient care outcomes and health indicators.

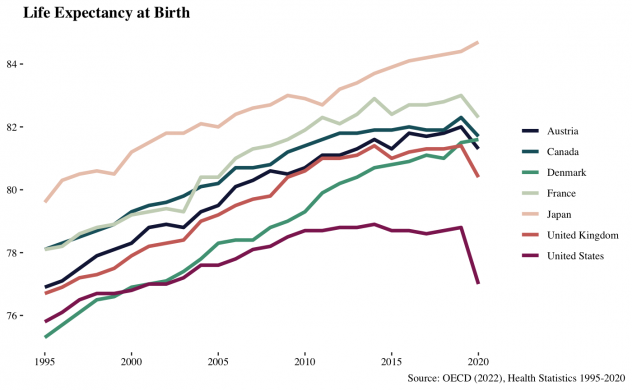

Figure 4

Even in states with the highest life expectancies, Americans are more likely to live much shorter lives than citizens of other nations. As a whole, the U.S. is 47th in the world for life expectancy at birth. However, aside from policy failures that delay access to and decrease the quality of healthcare services, other areas of American society bear at least partial responsibility for the U.S.’s declining life expectancy. There are significant health disparities in the U.S. based on factors such as race, income, and geography. These disparities often result in differences in access to care, as well as differences in the quality of care received. Lifestyle factors such as poor diet, lack of exercise, and smoking can promote a range of chronic diseases, which can lower life expectancy as well. Further, the worsening opioid epidemic contributes to decreasing average life expectancy as overdoses and related deaths have increased significantly in recent years. Corrupted policies aren’t the only determinant in a lower life expectancy, but these other confounding elements demonstrate the required strength for a healthcare system to support a struggling population. Socioeconomic circumstances and external conditions outside the scope of a country’s healthcare system encompass numerous influences on life expectancy, but they don’t justify the lack of substantial access.

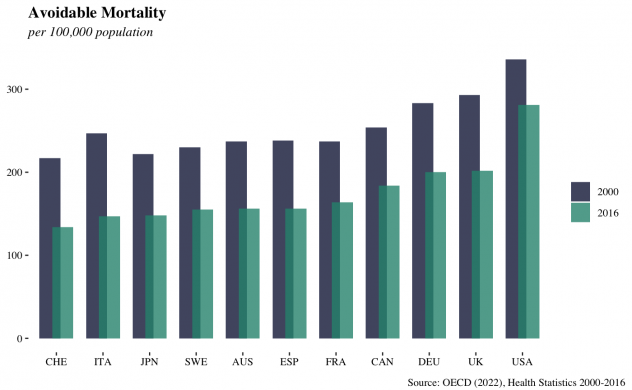

Figure 5

Measuring premature deaths caused by issues related to medical interventions more closely reflects the impact of policy on public health. Avoidable mortality, a metric developed by the OECD, refers to deaths before the age of 75 that could have been prevented through public health and primary prevention measures or effectively treated if detected early. In 2016, The U.S. had 281 avoidable deaths per 100,000 people – a far higher rate than most other OECD countries. With consistent cuts in insurance physician reimbursement and being 58th in world estimates of physicians per capita, medical professionals are underpaid and overworked. Ineffective infrastructure leaves the healthcare system underfunded and understaffed, limiting its ability to prevent and respond to crises. This contributes to the nation’s high avoidable mortality rates and differentiates it from other developed countries with more efficient and equitable systems. Compared to many other countries, Americans have a higher likelihood of experiencing premature mortality and are more likely to die from preventable conditions due to inadequate access to timely and appropriate medical care.

Conclusion

The state of healthcare in the United States highlights not only policy failures, but also broader societal issues that impact the well-being of its citizens. The lack of universal healthcare creates disparities in access to care that disproportionately affect already marginalized communities. While other developed countries generally have more substantial public health infrastructure and more equitable healthcare systems, the U.S. struggles with inefficiency and market manipulation, limiting its ability to prevent and respond to public health crises.

The free-market democracy, paired with the inalienable rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness are values held dear to American identity. A system built on the former is presently compromising on the latter. For more than a decade, administrations have been putting bandaids on a system with multiple, severe wounds. Reform is now imperative, but how the nation goes about this reform will determine where its priorities lie. Something must be compromised, whether it be the capitalist for-profit approach to medicine or the welfare of American citizens. Nothing is entirely free, especially something as costly as healthcare. Free healthcare doesn’t seem to be a reasonable solution, especially in the United States of America, where a government lacking proper incentives so readily pushes incurred costs onto its citizens. The practical approach would emulate examples of cost-containment and insurance approaches set by countries like Canada, the United Kingdom, Austria, France, or Japan. Government negotiation or regulation of markets is often opposed on the grounds of undermining democracy, but applying this to drug pricing or insurance rates is an ideological flaw. Healthcare should be treated like the right the Declaration of Independence suggests rather than a typical market good to profit from. Preservation of capitalism or protection of public welfare, which runs deeper through the nation? The more likely answer may very well acknowledge that the U.S. healthcare system is like a raging wildfire—out of control, burning through resources, and leaving us all to wonder if anyone can find the hose before everything turns to ash.

References:

- https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/observations-trends-prescription-drug-spending

- https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/88c547c976e915fc31fe2c6903ac0bc9/sdp-trends-prescription-drug-spending.pdf

- https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/bc582e25376d714694524a492fb15f36/international-prescription-drug-price-comparisons.pdf

- https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/private/pdf/187586/Drugspending.pdf

- https://assurance.com/medicare-products/what-happens-when-your-doctor-refuses-medicare/#:~:text=Why%20Do%20Some%20Doctors%20Not,higher%20fees%20for%20their%20practice

- https://catalyst.phrma.org/how-much-are-hospitals-marking-up-the-price-of-medicines-the-answer-may-surprise-you

- https://data.oecd.org/healthstat/life-expectancy-at-birth.htm

- https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/bio16610w18/chapter/turing-pharmaceuticals-a-glimpse-into-controversial-drug-pricing/

- https://finance.yahoo.com/news/heres-why-valeant-worrying-deutsche-161940520.html?guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAAF8XodqK_Jo2Q6REkneaf4HqAI5DoUdr3k8xwCyB23CH0bj2vB8lw8-ptCO5RQ2K7joxybUYB9G3iWfVytk62If2mapxlA-44cC-tpCoKoGEbC9idTCD8fI2JQs-LVS3Z5BjAH8hMepdiP4WHPccmz75FAqI_bkEb7EhO-FjqCfX

- https://healthpolicy.usc.edu/research/flow-of-money-through-the-pharmaceutical-distribution-system/

- https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2785480/

- https://kffhealthnews.org/news/mallinckrodt-orphan-drug-acthar-turned-cash-cow-as-drugmaker-raised-price-to-40000-per-vial-emails-show/

- https://locumstory.com/spotlight/physician-workload-survey-2018/

- https://magazine.wharton.upenn.edu/digital/an-end-to-overpricing-what-big-pharma-price-hikes-mean-for-health-care/

- https://oversightdemocrats.house.gov/sites/evo-subsites/democrats-oversight.house.gov/files/Mallinckrodt%20Staff%20Report%2010-01-20%20PDF.pdf

- https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=HEALTH_STAT

- https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=SHA

- https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/doctors-per-capita-by-country

- https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/M19-2818

- https://www.aging.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Drug%20Pricing%20Report.pdf

- https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/prior-authorization/how-insurance-companies-red-tape-can-delay-patient-care#:~:text=Thirty%20percent%20of%20the%20doctors,on%20a%20prior%2Dauthorization%20request

- https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/competition-health-insurance-us-markets.pdf

- https://www.americanprogress.org/article/following-the-money-untangling-u-s-prescription-drug-financing/

- https://www.brookings.edu/articles/five-things-to-understand-about-pharmaceutical-rd/

- https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-hutchins-center-explains-prescription-drug-spending/

- https://www.businessinsider.com/price-of-naloxone-narcan-skyrocketing-2016-7

- https://www.businessinsider.com/tuberculosis-drug-price-hike-rescinded-2015-9

- https://www.cbo.gov/publication/57721

- https://www.cbo.gov/publication/57772

- https://www.cbo.gov/publication/58180

- https://www.cbo.gov/publication/59035

- https://www.cbsnews.com/news/huge-price-surge-for-another-old-drug-called-off/

- https://www.cbsnews.com/news/turing-pharmaceuticals-ceo-martin-shkreli-defends-5000-percent-price-hike-on-daraprim-drug/

- https://www.cms.gov/data-research/statistics-trends-and-reports/national-health-expenditure-data/nhe-fact-sheet

- https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/nationalhealthexpenddata/downloads/nhe-deflator.pdf

- https://www.cnbc.com/2020/03/11/nearly-1-in-4-americans-are-skipping-medical-care-because-of-the-cost.html

- https://www.cnn.com/2018/06/29/health/acthar-mallinckrodt-questcor-price-hike-trevor-foltz/index.html

- https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/jan/us-health-care-global-perspective-2019

- https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2023/jan/us-health-care-global-perspective-2022#:~:text=The%20U.S.%20has%20the%20highest,hospital%20beds%20per%201%2C000%20population

- https://www.drugchannels.net/2024/02/latest-cms-data-reveal-truth-about-us.html

- https://www.drugs.com/price-guide/acthar#:~:text=The%20cost%20for%20Acthar%20injectable,on%20the%20pharmacy%20you%20visit

- https://www.fiercebiotech.com/biotech/ten-year-data-on-pharmaceutical-mergers-and-acquisitions-from-dealsearchonline-com-reveals

- https://www.fiercepharma.com/pharma/valeant-s-price-hike-strategy-goes-far-beyond-two-high-profile-increases

- https://www.forbes.com/sites/bartiescott1/2016/03/16/valeant-ceo-michael-pearson-lost-two-thirds-of-his-billion-dollar-fortune-in-a-year/?sh=783bc37c6c41

- https://www.forbes.com/sites/brucejapsen/2023/03/13/physicians-say-health-insurer-prior-authorization-is-rising-and-so-are-care-delays/?sh=5fcbc5635bd6

- https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20220909.830296/#:~:text=Administrative%20Spending%20Accounts%20For%2015%E2%80%9330%20Percent%20Of%20Health%20Care%20Spending,-It%20can%20be

- https://www.healthcarefinancenews.com/news/about-1-5-hospitals-mark-drug-prices-least-700-percent-study-finds

- https://www.healthcarenavigation.com/physicians-opting-out-of-medicare/

- https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/how-do-prescription-drug-costs-in-the-united-states-compare-to-other-countries/#Per%20capita%20prescribed%20medicine%20spending,%20U.S.%20dollars,%202004-2019

- https://www.hklaw.com/en/insights/publications/2023/02/another-one-bites-the-dust-doj-pulls-3-policy-statements

- https://www.ibtimes.com/tuberculosis-drug-cycloserines-massive-price-hike-rodelis-therapeutics-rolled-back-2107884

- https://www.investopedia.com/articles/personal-finance/080615/6-reasons-healthcare-so-expensive-us.asp#:~:text=The%20United%20States%20healthcare%20system,of%20the%20nation’s%20healthcare%20costs

- https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/explaining-the-prescription-drug-provisions-in-the-inflation-reduction-act/#bullet01

- https://www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/key-facts-about-the-uninsured-population/

- https://www.latimes.com/business/la-fi-senate-drug-price-study-20161221-story.html

- https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare/our-insights/administrative-simplification-how-to-save-a-quarter-trillion-dollars-in-US-healthcare

- https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/over-counter-narcan-cost-opioid-overdose-drug-rcna80665

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK603242/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2659297/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4191486/

- https://www.norc.org/NewsEventsPublications/PressReleases/Pages/survey-finds-large-number-of-people-skipping-necessary-medical-care-because-cost.aspx#:~:text=SAN%20FRANCISCO%2C%20CA%20%E2%80%94%20March%2026,of%20Chicago%20and%20the%20West

- https://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/12/business/valeant-promised-price-breaks-on-drugs-heart-hospitals-are-still-waiting.html#:~:text=In%202015%2C%20the%20price%20of,vial%2C%20a%20718%20percent%20increase

- https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/data/oecd-health-statistics/system-of-health-accounts-health-expenditure-by-function_data-00349-en

- https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/fact-sheets/2018/02/a-look-at-drug-spending-in-the-us

- https://www.pgpf.org/blog/2023/01/why-are-americans-paying-more-for-healthcare

- https://www.pgpf.org/infographic/spending-on-prescription-drugs-has-been-growing-exponentially-over-the-past-few-decades

- https://www.rand.org/health-care/projects/hospital-pricing.html

- https://www.rand.org/news/press/2021/09/10.html

- https://www.rand.org/news/press/2024/02/01.html

- https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA2519-1.html

- https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA788-3.html

- https://www.rand.org/randeurope/research/projects/2023/impacts-of-increasing-cost-transparency-requirements-in-pharmaceutical-research.html

- https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSL1N12N1PL/

- https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/oct/19/naloxone-price-soars-opioid-overdoses

- https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/health/2023/01/30/drug-price-increases-2023/11084913002/

- https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/health/2023/02/28/americans-lack-primary-care-provider-report/11359096002/

- https://www.westhealth.org/press-release/112-million-americans-struggle-to-afford-healthcare/

- https://www.wsj.com/articles/pharmaceutical-companies-buy-rivals-drugs-then-jack-up-the-prices-1430096431

- https://www.wsj.com/articles/valeant-steering-away-from-aggressive-price-increases-officials-tell-senators-1461790103

- https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/surveys/2021/oct/comparing-nations-timeliness-and-coordination-health-care

- https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/quality-u-s-healthcare-system-compare-countries/

- https://www.commonwealthfund.org/international-health-policy-center/countries/switzerland

- https://www.commonwealthfund.org/international-health-policy-center/countries/sweden

- https://www.who.int/data/gho/whs-annex/

Featured Image by NBC News