CHAZEL HAKIM – APRIL 7TH, 2021

EDITOR: NORA GONG

Picture this: One day you acquire a fortune of money from an inheritance. However, you decide to donate the money instead of keeping it, but only if your donation helps as many living beings as possible. Now here’s a question: Given your one condition, which charities should give most of your money to? Should you help endangered animals, for example, by donating to the World Wildlife Fund? Or should you help people in danger of catching malaria by donating to the Against Malaria Foundation?

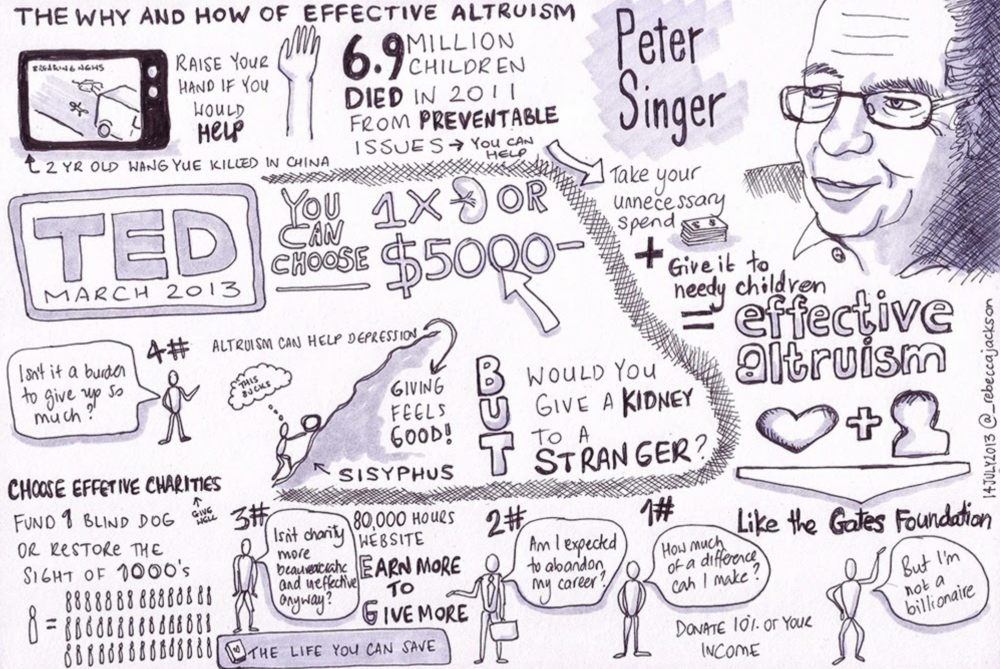

Questions like these are at the center of a growing movement known as “effective altruism.” Started in the late 2000s, the ideas of effective altruism have gained momentum worldwide by riding on the following, broader question: Given the limited amount of resources in the world (time, money, talent, etc.), how do you possibly maximize the amount of good you can do? A multitude of people—ranging from philosophers to philanthropists—now work in line with the philosophy, and several organizations such as Centre for Effective Altruism, 80000 Hours, and GiveWell have sprung up to broaden its reach.

At heart, effective altruism is just an economic idea. Economists seek to maximize consumer utility given their budget constraints, while effective altruists similarly seek to maximize the good of the world given their scarce resources (time, money, talent, etc.). The important difference lies in the definitions: Utility is simply a measure of consumer preferences, but the word good is a much more complicated philosophical notion. How exactly can one decide which charities, career paths, or research areas bring about more good than another? Is it if it saves more lives of people or animals? And if so, how do you decide which ones effectively do so?

To approach this philosophical uncertainty, effective altruism relies on a discrete solution not far from the methods of the economics discipline: heavy empirical evidence. One of the most prominent supporters of effective altruism, British philosopher William MacAskill, sums up this point succinctly in his essay on the philosophy: “As I and the Centre for Effective Altruism define it, effective altruism is the project of using evidence and reason to figure out how to benefit others as much as possible, and taking action on that basis.” What brings about the most good in the world, in other words, is whatever the empirical evidence points to.

One of the best examples of this evidence-based approach is effective altruists’ support of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in development economics. For those unfamiliar with the term, development RCTs are social science experiments used to test the effect of an intervention (cash transfer, education subsidy, etc.) in a developing country. Although controversial, development RCTs have also proven successful for helping economists discover cost-effective methods to alleviate poverty, some of which include providing deworming drugs or malaria nets to those who need but cannot afford them (for a more in-depth look at the use of RCTs in development economics, check out this BER article).

Effective altruists do not take these development RCTs for granted. In fact, these studies are a gold mine of empirical evidence to decide how to do the most good, specifically in the area of helping the world’s poor. The effective altruist group GiveWell, which analyzes how well charities use the funds given to them, has used these findings as evidence to declare several charities focusing on RCT-backed interventions as the “most effective” ones around the world. And in terms of actual donations, GiveWell has also moved $161 million worth of donations to these RCT-backed charities while the Effective Altruism Global Health and Development fund has also provided most of its $13,000 worth of funds to the same types of causes.

Though most obvious in terms of “doing good,” charities are not the only areas that effective altruists have attempted to bring empirical evidence to. Career choice has also become a heavy subject of interest for the community, which is not necessarily surprising given that labor, like money, is a limited resource for helping others. Another effective altruist organization, 80000 Hours, is the most prominent example of this case. One need only scan through their extensive list of “high-impact” careers to notice the plethora of research used for their recommendations, which ranges from obvious careers like non-profit work to more surprising ones like quantitative finance (80000 Hours assumes you donate a portion of your high earnings for the latter, which they call “earning to give”).

Yet effective altruism has not been immune from criticism, especially in the area of charity. Given that people usually view charitable giving as an emotional rather than rational act (e.g. we might donate because we feel bad for someone), effective altruism’s total removal of emotion may seem distasteful to many despite its rational approach. Some critics have gone so far as to label effective altruism as “cold” or “moralistic.” In an article on the philosophy, psychologist Alan Jern reasons that while rationalizing charity is effective in its own right, it is still too unnatural for human behavior to catch on in the long run. Emotional entanglements such as family obligation cloud the rational aspect of effective altruism: if it comes to it, most people just care more about saving the lives of those close to them rather than those they don’t know.

A more nuanced criticism of the philosophy of effective altruism concerns its potential hindrance to institutions and institutional changes. Some point out that effective altruists’ focus on charities as the most effective means to do good in the world eclipses traditional methods to help people, most notably public services. These worries have been amplified by MIT economist Daron Acemoglu, who points out that replacing public services with charities may erode public trust in the state sector and lead people away from engaging in politics as a whole. Others also assert that the effective altruism movement, despite all its proclamations of “doing the most good possible,” ignores support for avenues of broader, institutional changes that may do more good for people in the long run. RCT-backed charities, for example, are not likely to significantly improve poverty in a developing country despite their widespread support by effective altruists. Endorsing high-paying careers in finance and banking as a means of doing good will probably also not lead to any radical economic changes anytime soon.

On the other hand, the effective altruism community has been diligent in responding to the criticisms leveled against them. In an article on their website, 80000 Hours discusses many of the common criticisms—which they call “misconceptions”—of effective altruism. Most notably, they take issue with the notion that effective altruism is only concerned with solving poverty and charitable giving, arguing that the philosophy can be used in other areas such as career coaching and global priorities research (i.e. figuring out the most important future global problems). 80000 Hours also contends that effective altruism is not ignorant to systemic change despite its focus on charity and endorsement of high-paying careers. According to them, many effective altruism organizations do work on systemic problems, some of which include research relating to issues of voting rights, animal welfare, and international migration.

Despite backlash, effective altruism overall is still a new and relatively small movement to this day. Whether the empirical approach of the philosophy has any real merit is hard to tell right now, especially without enough information on related organizations’ long run impacts. Given this lack of evidence, the next few years (or potentially decades) will serve as a test of whether the philosophy’s empirical method is truly effective. Maximizing the most good someone can do, after all, is not the easiest task in the world, and perhaps approaching the mission empirically will actually help people reach that goal. Or it will not. Let’s just let the evidence decide.

Featured Image Source: The Point

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.