OLIVIA GINGOLD – APRIL 1ST, 2019

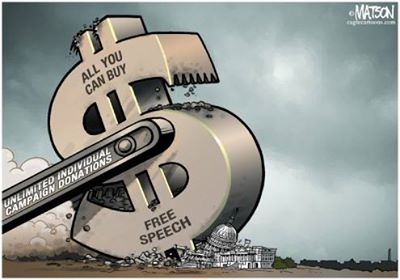

The definition of a democracy is a system of government by the whole population or all the eligible members of a state, typically through elected representatives. Nowhere in this definition is money or financing ever mentioned, and yet, in the 2016 Presidential Election, over $2.4 billion was used to finance the campaigns. The 2020 Presidential election is the first election ever in United States history expected to surpass $5 billion. This means the campaign finance for the presidential election has more than doubled in a single presidential election cycle. Campaign finance brings up a lot of issues, mostly centered around concerns that it is hindering the democratic process, but it may also be a way for individuals to contribute to causes about which they are especially passionate. There are also arguments that limiting campaign finance limits campaign speech, which is a precedent upheld in the 1974 Supreme Court case Bucky v. Valeo. The debate, as academic writer Milyo puts it, boils down to a tug of war between the liberal ideals of free speech on the one side and the democratic ideal of equal representation on the other.

Bucky v. Valeo was not the earliest instance of campaign finance, or the debates that accompany it. On the contrary, campaign finance has a long history in the United States, originating in the 17th and 18th century before the United States was even an independent country. Initially, regulation was focused on preventing bribes and limiting worker coercion. Workers were sometimes solicited at their jobs and even told they could lose their job if they did not contribute to an election. The 1970s marked a pivotal time in campaign finance history. Congress Created the FEC or the Federal Elections Commission which “required full reporting of campaign contributions and expenditures and … limited spending on media advertisements, [as well as] provided the legislative framework for PACs established by unions and corporations, which allowed unions and corporations to use treasury funds to establish, operate and solicit voluntary contributions for the PAC to be used in federal races.” These treasury funds were intended to be a public alternative to private funding, but have become more and more obsolete, with candidates foregoing them entirely in the two most recent presidential elections. The passage of Citizens United v. SEC and McCutcheon v. FEC in the last ten years have significantly relaxed regulations on campaign finance circa the 1974 Federal Elections Commission Act, under first amendment arguments similar to those made in the Bucky v. Valeo case.

Money for campaign finances is categorized into two separate denominations: hard money and soft money. Hard Money includes “money that has been raised in accordance with federal contribution laws.” Soft Money includes any type of donation to a party or another group that does not qualify as hard money. Soft money usually goes towards financing specific legislation (like propositions) or other issue-advocacy advertisements (planned parenthood and medicare are great examples). They can also be categorized as “independent expenditures,” or “interested money and non-interested money.”

In addition to the two different types of campaign money, there are four categorizations used to distinguish different contributing entities. These are:

- Individuals who contribute nothing over $200

- Large (individual) contributors whose contributions exceed $200

- Political Action Committees

- Self-financing

Only donors who give at least $200 have to disclose their names. The individual categories are self-explanatory, but the second 2 aren’t. Self-financing simply refers to situations where candidates use personal money from their net worth, income, and other sources to fund their campaign. Political Action Committees include 3 different types: “separate segregated funds (SSFs), nonconnected committees and Super PACs.” Separate Segregated Funds are committees which are established by large corporations or organizations and can only solicit funds from individuals associate with the respective entity. Nonconnected committees on the other hand aren’t sponsored by or connected to a specific organization and can therefore collect money from any member of the general public. Finally, Super PACs are independent political committees which can accept contributions from individuals, corporations, and other pacs, but can only spend them on independent political activity. Within these four categorizations are many different entities who can contribute like businesses, political action committees, national parties, 501(c) organizations, individuals, the public or the state, and dark money groups.

How does campaign finance break down on an economic level? Campaign finance is not captured in GDP when money is transferred from funder to the candidate, but when the candidate spends that money on campaigning like television ads, brochures, and the like, this money is captured in GDP as consumption. The campaign finance including presidential and Congressional elections in 2016 exceed 6.2 billion dollars which seems like a large sum to many everyday individuals, but this amount was still only .038 percent of National GDP in 2016. In light of this, arguments that it may help spur economic growth are easily discredited. Not only is it not a significant enough sum to have a real effect on the economy relative to the size of the current GDP, but other arguments state that the money funnelled into campaign finance would have been spent regardless, just on different things. In this case, campaign finance may be hurting the economy by reallocating money that would have otherwise been spent on productive goods that create jobs.

Could campaign finance be serving other purposes, even if it does not have a significant effect on economic growth? Undoubtedly. An interesting argument in favor of campaign finance focuses on redefining democracy from its narrow concept of “majority rules” to a more developed concept of “an institution that limits the inevitable inequalities of representation and participation to a tolerable level.” What majority rules fail to capture is how strongly and individual may prefer a certain policy or legislation. This can be broken down: for example, in an economy of 100 people, if 40 get 8 utils (a measure of happiness) from one vote, 480 utils are gained, but if 60 get 4 utils for one vote in opposition to the initial vote, then only 240 utils are gained. In this situation, the vote of the majority (60%) is the winner based on “majority rules,” but twice as many utils are lost. If the minority had won, 240 utils would have been netted. Although other institutions such as supermajority can help account for intensity of individual preferences, campaign finance can serve that same purpose. If people feel more intensely about something, they can finance institutions like PACs and Corporations who will represent candidates with favor to their cause. This significantly reduces the transaction cost of debating on important issues in which everyday people have a stake.

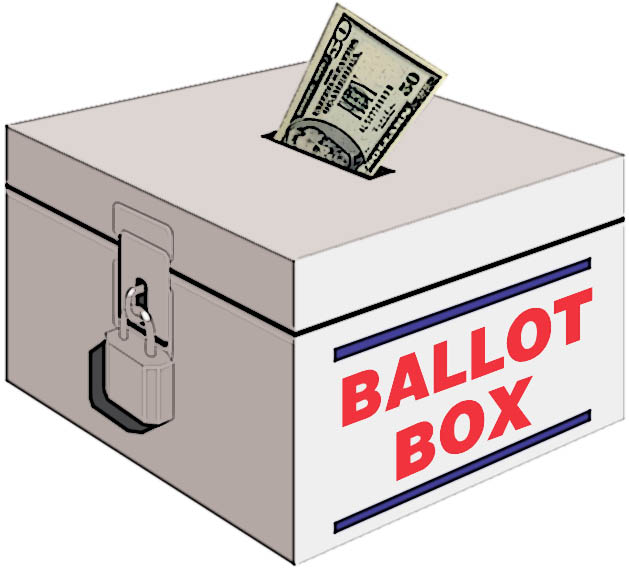

With that being said, barely half a percent of the adult population has given $200 or more to this year’s federal elections, but their donations account for more than 2/3 of campaign funds. Only one thousandth of a percent have given $10,000 or more, but this sum still accounts for 38 percent of the total campaign funds. Furthermore, racially and fiscally, there is privilege in donation—donors are older, whiter, and wealthier than America as a whole; often come predominantly from certain cities, like Washington DC; and specific industries, like finance, real estate, law, health care, oil, and gas.

If campaign finance had a relationship status on Facebook, it would be “It’s complicated.” On the one hand, it is true that campaign finance can be seen as an extension of free speech. It can also be regarded as a way for individuals to vote with their dollars, but the concentration of campaign donations in the hands of only a few pokes holes in the aforementioned argument. Ultimately, the vote is still out on campaign finance, but if one thing is for sure, even if the way it is regulated or dispersed is subject to change, the existence of it undoubtedly is not.

Note: this argument talks only on the structure and history of campaign finance, only briefly touching on regulation of campaign finance. For those more curious about campaign finance regulation, a history of it can be read here, an argument against it can be read here, and an argument for it can be read here.

Featured Image Source: Blue Jersey

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.