JEFFREY SUZUKI – NOVEMBER 21ST, 2019 EDITOR: AMANDA YAO

Toni Morrison, renowned author and Nobel Prize laureate in literature, remarked in her memoirs that “in this country, American means white. Everybody else has to hyphenate.” In this era of inflammatory claims, alleged concentration camps, and immigration bans, a sharp political divide has resurged in the United States on the topics of racism and bigotry.

Of course, racism and bigotry are nothing new. To be clear, racism and bigotry are distinct concepts. Bigotry is usually an individual bias that one has against a person for any reason. For example, according to the Washington Post, “long before Americans began associating Muslim immigrants with terrorism, they saw the Irish as terrorists who threatened U.S. national security. That’s right: The immigrant group that today most Americans associate with leprechauns, the Blarney stone and Guinness beer was reviled as a band of foreign terrorists 150 years ago.” However, after a generation or two, this bias faded away as the children of Irish immigrants categorized themselves as White Americans. For our purposes, we define bigotry as discrimintation against a foreign-born person for differences in culture, accent, etc. On the other hand, racism is systemic and intergenerational. An oft mentioned example is the legacy of slavery and the bleak failures of Reconstruction to the present to bring about true racial equality. For over a century after the abolition of slavery, state laws and domestic terrorism prevented generations of African Americans from participating in politics. In mainstream political discourse, bigotry and racism are often conflated for understandable reasons. Japanese Americans, many who of whom had never seen Japanese soil, found themselves in internment camps during World War II, while the Roosevelt administration trusted the vast majority second-generation German Americans to fight the Germans.

We seek to analyze the effect of this overlap by asking the following question: how does native or foreign-born status affect income when accounting for race? That is, how do the respective incomes of foreign-born Hispanic/Latino, Asian, Black, and White workers in the US compare to those of their native-born counterparts? For example, some have argued that Black immigrants are an ‘invisible’ model minority for their relatively high academic achievements. Others argue that Asians are an American “model minority”—a term used to refer to a group perceived as particularly successful, especially in a manner that contrasts with other minority groups. We will put these claims to the test.

The results up front:

For those who do not have the time to read the whole article, here are the results of our analysis and our conclusions.

The average native-born worker in the US earns significantly more than the foreign-born worker. However, when broken down into racial categories, only one foreign-born group earns significantly less than their native-born counterparts: Hispanics/Latinos, earning 16.2% less. Interestingly, foreign-born White and Asian workers actually earn more than their native-born counterparts. The average foreign-born Black worker sees no significant difference in income when compared to their native-born peers, possibly debunking the idea that foreign-born Black workers are a model minority.

Upon further investigation, we found that differences in income across birthplace in the White and Hispanic/Latino groups could be attributed to discrepancies in education levels. The average foreign-born White person has more education than their native-born counterpart, while the average foreign-born Hispanic/Latino person has less education than their native-born counterparts. The education levels of the average Asian and average Black person in the US were roughly the same regardless of native-born status.

In broadening our analysis to observe differences across racial categories, the only group not significantly disadvantaged relative to Whites in terms of median income is Asians; they earn significantly more than Whites in both the native-born and foreign-born groups. Hispanics/Latinos and Blacks are relatively disadvantaged, on the other hand.

In terms of analysing the effect of bigotry, we find that bigotry against immigrants may be a factor for Blacks and Hispanics/Latinos when earning income. We were unable to find evidence of bigotry against foreign-born Whites or foreign-born Asians due to limitations in our data set.

For those interested in the details of how we obtained our results, please continue reading.

Analysis:

First, we remind readers that statistical significance of a variable is defined as having a t-score equal of greater than 1.96 (in absolute terms). Due to a lack of panel data from the BLS, we assume that the difference between median and mean income for all groups in subsequent hypothesis testing is identical. That is, if the mean is $50 dollars higher than the median for native-born White workers, then it will be the same for foreign-born Asian workers, native-born Black workers, etc. This assumption results in a difference between medians equivalent to a difference in means, allowing us to conduct our two-tailed hypothesis test.

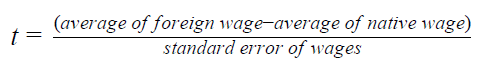

We first calculate whether there are statistically significant differences between being foreign and native-born on income without accounting for race. The null hypothesis is quite simple: there is no difference between the groups; differences between groups in our sample are due to chance.

We calculate our t-score with the following:

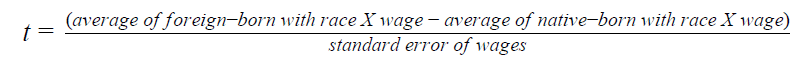

Then, we determine whether there are statistically significant differences in income within racial groups (e.g. White, Black, Asian, Hispanic/Latino) between native-born and foreign-born individuals. The null hypothesis is similar to the native vs. foreign-born comparison of our holistic sample: there is no difference between native-born and foreign-born wages in each racial group; differences in our sample are due to chance.

In the event that the differences are statistically significant, we will estimate the modifiers associated with native-born status and race.

We calculate the standard error of wages using the following equation:

![]()

We calculate the standard deviation of weekly wages using Bureau of Labor Statistics data under “CSVs single file” under annual 2018 data. We will assume that this collection of average weekly wages is the population because there does not appear to exist a dataset as comprehensive as this—it has 3,575,867 observations. After filtering out all non-income earnings, our standard deviation for weekly wages is $732.55.

Our findings:

Foreign-born vs. Native-born:

With a sample size of 115,566, we calculate our standard error to be $2.154876 per week.

The average person in the foreign-born population earned $758 per week.

The average person in the native-born population earned $910 per week.

This represents t = 70.53771 with a corresponding p-value of virtually 0. Therefore, we can assume that there is a real difference in earnings from being a foreign-born person employed in the US—$152 less per week.

Foreign-born vs. Native-born within Racial Groups:

Whites:

With a sample size 70,811, we calculate our standard error to be $2.752878 per week.

The average foreign-born White person in the US earned $1,083 per week.

The average native-born White person in the US earned $986 per week.

This represents t = 35.23586 with a corresponding p-value of virtually 0. Therefore, we can assume that there is a real difference in earnings from being a foreign-born White person employed in the US—earning $97 more per week.

Blacks:

With a sample size of 13,554, we calculate our standard error to be $6.292215 per week.

The average foreign-born Black person in the US earned $699 per week.

The average native-born Black person in the US earned $697 per week.

This represents t = 0.3178531 with a corresponding p-value of 0.6247018. Notably, this does not constitute statistical significance. We fail to reject the null hypothesis that there is no difference between the incomes of a foreign-born and native-born Black worker in the US.

Asians:

With a sample size of 7,132, we calculate our standard error to be $8.674243 per week.

The average foreign-born Asian person in the US earned $1,129 per week.

The average native-born Asian person in the US earned $1,065 per week.

This represents t = 7.378165 with a corresponding p-value of virtually zero. We can assume that there is a real difference in earnings from being foreign-born as an Asian person in the US—earning $64 more per week.

Hispanic or Latino:

With a sample size of 19,615, we calculate our standard error to be $5.230499 per week.

The average foreign-born Hispanic/Latino in the US earned $621 per week.

The average native-born Hispanic/Latino in the US earned $741 per week.

This represents t = -22.94236 with a corresponding p-value of virtually zero. We can assume that there is a real difference in earnings from being foreign-born as an Hispanic or Latino person in the US—earning $120 less per week.

A Seemingly Paradoxical Result: A Lesson in Medians

To reiterate, in examining the holistic sample without categorizing by racial group, foreign-born workers earn less than their native-born counterparts. However, upon accounting for race, foreign-born Whites and Asians earn more than native-born Whites and Asians, Blacks earn roughly the same regardless of birthplace status, and foreign-born Hispanics earn significantly less than their native-born peers.

A striking result is that, although the average foreign-born worker in the US earns $152, or 16.7%, less than the average native-born worker, there is only one racial group whose foreign-born individuals earn significantly less than their native-born counterparts: Hispanics/Latinos, earning $120 less. How could every other foreign-born subgroup within the other racial groups marginally out-earn their native-born peers, yet the average foreign-born worker still earns less?

It is possible that our use of medians is responsible for this contradiction. By definition, medians are the value of the 50th percentile of earnings. Means, on the other hand, are overall averages. Contrary to our assumption earlier, it is very possible that the distributions of incomes within each racial group have differing degrees of skew. For example, foreign-born White earners could have a far more unequal distribution of wages than their native-born counterparts; the use of medians conceals these differences. Unfortunately, the BLS did not fulfill our request for their panel data, forcing us to substitute our means with our medians. If we had the data, we would perform these significance tests with means and run regressions based on factors, such as education level and industry.

In its article, the BLS makes definitionally incorrect statements, conflating median and means. For example, according to its publication, “Hispanic foreign-born full-time wage and salary workers earned 83.8 percent as much as their native-born counterparts in 2018.” This is a misleading statement. A more accurate statement would replace “Hispanic foreign-born […] workers” with “the average foreign-born Hispanic […] worker.”

Based on our analysis, we cannot draw conclusions spanning entire racial groups. However, due to our usage of medians, we can observe differences between the middle person in each group, which is definitionally true since we are using medians.

The Role of Education:

First, according to the BLS report, foreign-born individuals earn less than their native-born counterparts at every education level except for bachelor’s or higher (in fact, foreign-born workers earn more at that level); our average foreign-born worker would naturally earn less than our average native-born worker, since only a minority of people have completed higher education.

Taking race into account, we can observe the education level of each racial group. We calculate from the table given in the BLS report that 56.76% of the White foreign-born labor force had a bachelor’s degree or higher. Meanwhile, only 44.78% of the White native-born labor force has a bachelor’s or higher. Therefore, the average White foreign-born worker holds a bachelor’s, while the average White native-born worker does not. The average native-born White worker does have some sort of college degree. This difference in education may explain the “bonus” that foreign-born Whites take in. Political economist Mark Blyth, himself a Scottish immigrant to the US, once said, “immigration to me is where another person from another interesting country has a PhD.”

For Asians, education levels are quite similar—the majority of the labor force in both the foreign and native-born groups are highly educated, at 63.02% and 64.95% respectively. It makes sense that the earnings gap of $64 between Asians is less pronounced than the earnings gap between Whites of $97—the median Asian person in both groups is highly educated.

For the average Black person in both groups, there is no substantial difference in education levels. The average Black person, in both the native-born and foreign-born groups, has a college/associate degree. There is a difference in the percentage share of the two groups with a bachelor’s degree or above; 38.06% of their foreign-born population and 30.52% of their native-born population has a bachelor’s. However, we do not see a substantial difference in median income that results from this higher education gap; a natural consequence resulting from the exclusion of higher education from the use of medians. We may have observed a difference in income due to a higher education gap if mean data was available.

Finally, for Hispanics and Latinos, there is also a substantial difference in education level. While 26.76% of the native-born population has a bachelor’s degree or higher, only about 15.39% of the foreign-born population does. What explains the difference in median income is that the average native-born Hispanic/Latino has some college/associate degree; the average foreign-born Hispanic/Latino only has a high school degree. In other words, native-born Hispanics/Latinos are better educated on average when compared to their foreign-born counterparts. It could very well be the case that the foreign-born population has higher poverty rates, because of factors such as bigotry. For example, the incendiary rhetoric by President Trump surrounding Hispanic/Latino undocumented immigrants might have intensified negative economic stereotypes about foreign-born Hispanics/Latinos in general. In 2018, 4 in 10 Latinos reported discrimination and, since 2016, hate crimes against them have steadily risen; we speculate that foreign-born Hispanics and Latinos may experience this discrimination worse than their native-born counterparts.

Overall, the discrepancy between the earnings of the average foreign-born White worker and the average native-born White worker may be rooted in the comparatively higher education levels of the former. There does not appear to be significant discrepancy in education between the native-born and foreign-born subgroups within the Asian and Black racial categories; it is possible that foreign-born Asians may benefit from some other factors, perhaps differences in profession, upbringing, or existing connections in the US.

Final Thoughts:

One surprise is that bigotry against foreigners doesn’t seem to appear in our data for every group, except for Hispanics. The potential role of bigotry in negatively impacting foreign-born Hispanic/Latino incomes may stem from the recent surge of anti-immigrant sentiment and rhetoric targeting Hispanics/Latinos specifically in the United States.

Overall, the results of our analysis produce this ranking of median incomes by birthplace and racial group, ordered from highest to lowest:

- Foreign-born Asian

- Native-born Asian

- Foreign-born White

- Native-born White

- Native-born Hispanic/Latino

- Either foreign or native-born Black

- Foreign-born Hispanic/Latino

However, this ranking does not capture income inequalities within each racial group. For example, arguments such as the Asian Model Minority argument are misleading. While Asians do earn more in terms of absolute dollar amount, they are 50% more likely to be impoverished than Whites when taking cost-of-living into account.

Every racial group except for Hispanics/Latinos is adjacent to the native/foreign-born counterpart in the rankings, possibly implying that the effect of race on income is higher than the effect of the location of birth. If there is any evidence of bigotry against foreigners, it is the vast disparity in earnings between the foreign-born and native-born Hispanic/Latino population.

For over a century, immigrants have comprised a significant share of the United States. From 1860-1920, the share of immigrants was roughly the same, fluctuating from 13-15% of the US population. As of 2017, 44.5 million immigrants reside in the United States, a number that represents 13.7% of its population. In other words, we do not live in a unique era regarding our large share of foreign-born. Whether it is the Irish, the Chinese, the Japanese, or Hispanics and Latinos, immigration has indisputably remained a persistent point of contention throughout the entirety of US history, and will likely continue to be so for decades and perhaps centuries. The best that we can do is to continue researching these issues, elect representatives, and pressure the political establishment to enact better social and economic justice measures.

Featured Image Source: Getty Image

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.