MATTHEW FORBES – APRIL 25TH, 2018

A fish doesn’t realize it’s swimming in water unless it’s abruptly yanked out of the ocean. There are certain things so basic and interwoven in our everyday lives that it becomes a challenge to step back and fully comprehend it. Advertising is one such thing. To live a modern American life is to spend your days besieged by companies trying to sell you things. Advertising is everywhere, whether a person is conscious of it or not. There are the more obvious advertisements, such as those one finds during commercial breaks on television or on billboards overlooking a freeway. But most advertising is far subtler than that. Instead, it comes in the form of sponsored articles written by major news outlets, the social media teams at corporations like Wendy’s that try to give their business a “personality” and make it seem more hip or friendly, or the pieces of clothing people wear with a company’s logo plastered on it.

Since advertising is so present in our lives, we must ask the question: what value does it actually create and what effect does it have on our society?

In economics, it is assumed that people have an innate demand for goods. People want medicine, food, or fidget spinners and businesses form in order to meet those demands. If exchanges between businesses and people are voluntary, then both sides benefit from the transaction and society as a whole becomes better off. However, demand is a malleable force, and this is recognized in most economic models. Demand can shift due to changes in consumer confidence, income, or personal tastes, among many other things. This is what advertising is ultimately trying to do: increase people’s demand for a certain product so that it will fetch a higher price and quantity sold in the market.

But if people have to be convinced that they need to buy a certain product, can it really be said that the production of that product is satisfying our needs and making society better off? If a consumer is only willing to exchange their money for a product because of psychological manipulation, is that transaction actually beneficial and fair to both sides?

Economist John Kenneth Galbraith says that it cannot. In his book, The New Industrial State, he argues that, before industrialization, market societies operated in accordance with an “original sequence”. In these societies, businesses catered to consumers and produced products according to consumer demand. Once these societies go through industrialization, a “revised sequence” develops where powerful corporations are able to control consumer demand through methods like advertising. The market system then functions to satisfy the needs of these corporations rather than consumers. Demand is created to meet an existing supply of products, rather than products being created to meet an existing level of demand. This results in resources and manpower being wasted, which instead could be spent on endeavors that could satisfy “true” demand.

There are other ways advertising actively harms society. For one, there is an enormous amount of shaming in advertising, as people are more likely to buy a product if they feel bad about themselves. Many advertisements have implications like “people won’t find you attractive unless you drive a certain car” or “you won’t be fun at parties unless you drink a lot of beer”. These create general feelings of inadequacy and make those who watch them feel miserable about themselves. There’s also the issue of unhealthy products being advertised, such as Winston Cigarette commercials that aggressively targeted children. Finally, as news sources and creative outlets have to increasingly rely on advertisements in order to stay financially viable, there arises a worrying fusion between the two. Can a news source really be unbiased in its reporting if it depends on ad revenue from controversial corporations? Can a work of art like a movie or book really remain artistically genuine if it has to include product placement?

One argument often used in defense of advertisements is that they inform the public about certain products that they otherwise would not have known about. However, this information would then be coming from a biased source. Consumers might become aware of a product’s existence through an advertisement, but if they are also given a wildly incorrect impression of the product from the advertisement then they are not necessarily better off with this information.

However, if we accept that advertising is harmful and thus requires regulation, then many more questions arise that must be dealt with. Who should be given the power to regulate? Would this regulation too harshly constrict individual freedoms, like the freedom of speech? Shouldn’t we instead depend on individual responsibility? Don’t some advertisements have value in-and-of-themselves, like tv commercials that are genuinely funny? And what even counts as advertising? Should companies not be allowed to write the name of their brand in a fancy font?

Consumers also often don’t even know that they want something. If you were to ask a Civil War soldier in 1863 what brand of car he would like to drive or model of smartphone he would like to use, you would probably get a blank stare in return. Companies that create products that have never existed before must convince the public that what they are creating is useful, and the main way this is accomplished is through advertising.

Ultimately, markets only work to make humanity better off if consumers are sovereign in their economic choices. If consumers can be controlled, then markets no longer work for the benefit of consumers. Advertising offers a clear path for corporations to gain control over consumers, and as technology and knowledge about human psychology become more advanced this prospect becomes more likely.

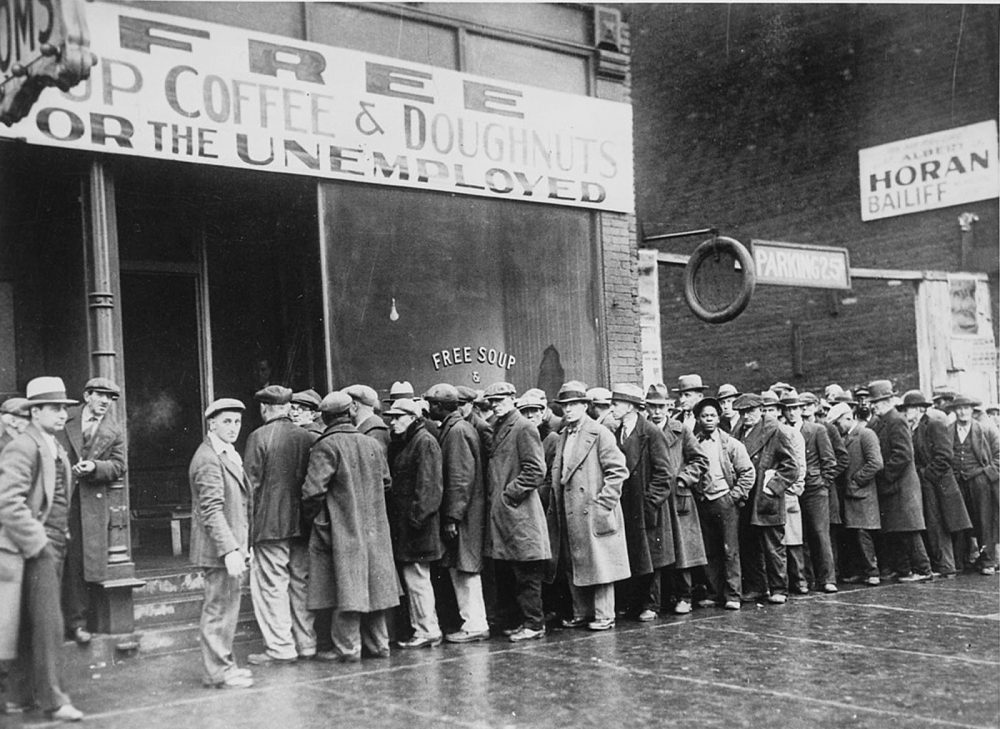

Featured Image Source: Media Education Foundation

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of The Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California at Berkeley in general.