DAVIS KEDROSKY – MARCH 18TH, 2021

EDITOR: RAINA ZHAO

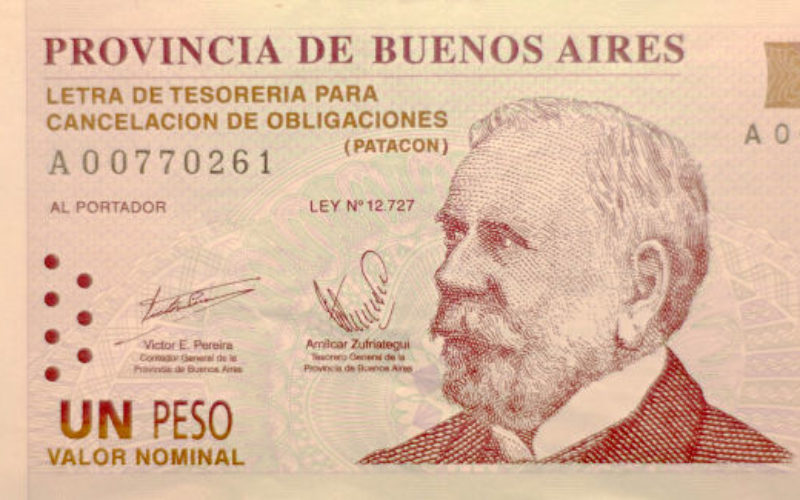

Overshadowed by the Wall Street Crash of 1929, the Depression of 1920-1921 appears, if at all, as a footnote to the history of the interwar United States. The title itself is somewhat of a misnomer; lasting only eighteen months, the recession period achieved neither of the popular criteria for qualifying as a true “depression” (two years of recession or a 10% fall in GDP). Yet the event, which saw a sharp rise in unemployment and a then-unprecedented currency deflation, holds a unique position in the annals of American financial governance, serving both as a formative lesson for the nascent Federal Reserve and a case study in postwar economic transition. Eminent scholars from the classical monetarist Milton Friedman to the economic historian Christina Romer have clashed over the catalysts and products of the Depression, and there is no complete consensus on what factors were responsible. Nevertheless, existing academic literature offers a common narrative incorporating multiple potential causes.

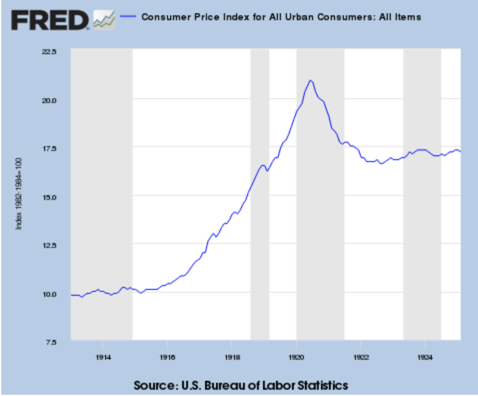

The United States emerged from the First World War riding an enormous economic expansion. Unemployment had fallen to just 1.4%; while inflation and productivity rose in unison, a prosperity fuelled the demand for wartime deliveries, which provided a boost to the nation’s surging manufacturing sector. But the cost of achieving this growth, unbeknownst to the populace, was perilously high. The Federal Reserve, chartered only in 1913, had been compelled to maintain low interest rates by the need to finance military operations. After the armistice, however, monetary policy remained lax, a stance designed to prevent capital losses on the final war bond offering, lower the costs of servicing outstanding debt, and facilitate a smooth shift to peacetime conditions.

As a result, inflation increased unchecked, to the growing consternation of policy advisors, and in 1919, the incumbent Wilson administration initiated austerity reforms. Government spending was cut by 75%, and the Federal Reserve increased the discount rate by 244 basis points—leading to interest rates upward of 7% by June 1920. Though the administration managed to quickly balance the budget, the disinflationary retrenchment presaged recession, especially coupled with the swarm of malignant economic factors then at work. These included the closure or retooling of munitions factories, the return of 1.6 million soldiers to the civilian labor force (a growth of 4.1%), and the weakening of union power. The erosion of workers’ bargaining power, against the backdrop of the transition from military to peacetime production, further suppressed wages and increased the short-term gravity of the inevitable slump.

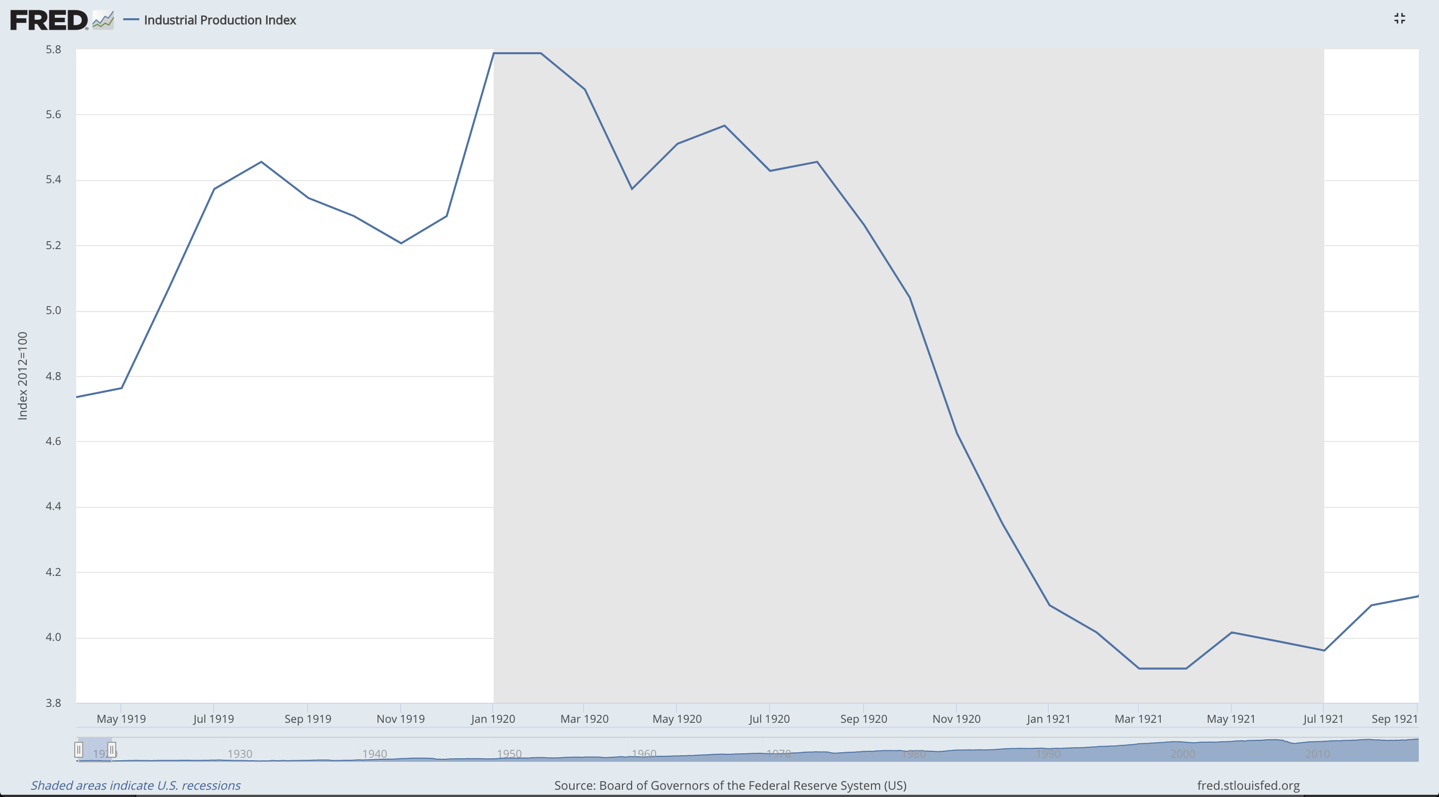

In January of 1920, when postwar industrial production reached its zenith, the promised downturn began to take hold. Production fell by 32.5% over the following year, a decline second only to the Great Depression in American economic history and occurring over a shorter span. At the same time, prices plunged by over 15%, and unemployment approached a startling 12%. The rate of business failures tripled and surviving enterprises saw average decreases of 75% in profits. Unsurprisingly, stock prices plummeted—the Dow Jones Industrial Average dropped by 47%—leading to further public distress.

Immense controversy surrounds the exact nature of the government response, with the warring houses of economic thought each trying to divert responsibility for the crash and claim it for the recovery. Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz argued that the Federal Reserve miscalculated the lag times inherent in monetary policy changes, leading the central bank to raise interest rates during the early stages of a recession. The effects of the November 1919 rate hikes had not set in, they argued, by the time new and more drastic steps were taken from January to June of the following year. This view aligns with their monetarist view of economic history, which places the management of the money supply by the central bank at the heart of policy analysis.

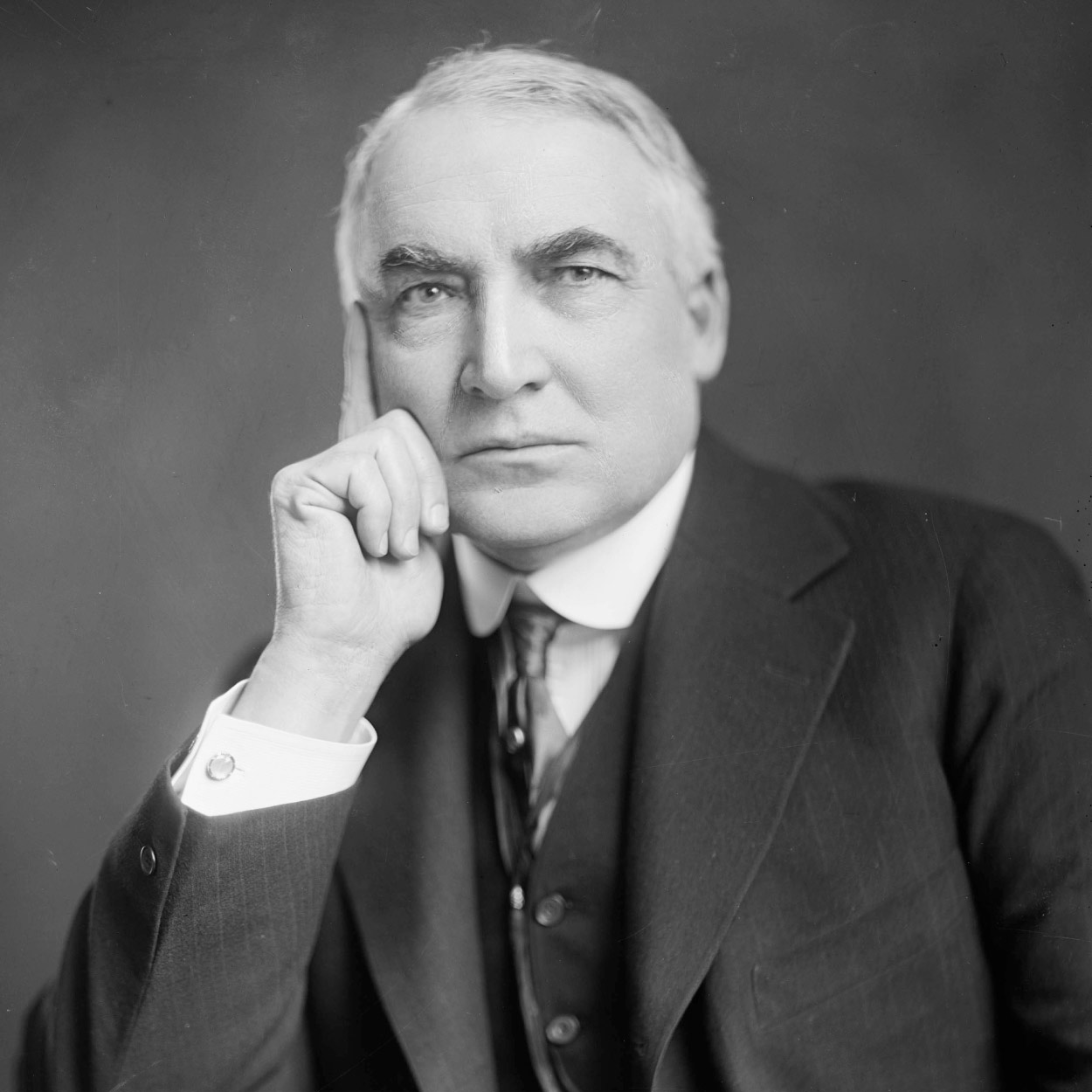

Austrian economists, most notably the Von Mises Institute’s Robert Murphy, have attempted to prove that the austerity begun by Wilson and continued by his successor Warren Harding prevented the crisis from reaching the depths of the Great Depression. Murphy attributes to the 65% reduction in federal spending between the 1919 and 1920 fiscal years—from $18.5 billion to just $6.5 billion—the surprisingly swift rebound (unemployment was 2.3% in 1923) into the “Roaring Twenties,” claiming that government severity “purged the rottenness from the system” and laid ground for “sustainable growth.” The shock, he claims, was merely a necessary readjustment in the face of changing economic conditions; one need only examine the Great Depression that followed Hoover’s “easy money” regime in 1933 to see the consequences of overreaction. “The free market works,” Murphy concludes. “Even in the face of massive shocks requiring large structural adjustments, the best thing the government can do is cut its own budget and return more resources to the private sector.”

However, the Austrian explanation does not fit the chronology. Harding, who took office at the recession’s nadir in March 1921 amid widespread frustration with Wilson’s frugality, actually increased federal revenues by enlarging the tax base (through a lowering of minimum income levels in each bracket) and oversaw the easing of interest rates. Indeed, this unintended “stimulus package” might have helped to abate the recession, allowing the American economy to rebound quickly. Far from empirically proving the efficacy of austerity, the Depression of 1920-21 may have provided an early, if inadvertent, model for a semi-interventionist response to economic adversity. At the very least, Harding’s policies barely affected a recovery already underway by the time he took office. As Paul Krugman closed a pithy column on the implications of the 1921 crisis: “do we have anything to learn from the macroeconomics of Warren Harding? No.”

In all likelihood, the highest compliment that can be paid to the Harding administration was that it did not stand in the way of an inevitable recovery. Given the youth of the callow Federal Reserve—less than a decade old in 1919—a short disinflationary contraction was probably the best possible outcome.

Featured Image Source: The White House

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.