Writer: Tim Roth, Editor: Kiet Hoa

When we think of economic slowdown, we usually imagine something grim: cities in decay, widespread unemployment, a government lurching toward default. Then there’s Japan, aging gracefully and calmly defying every Western economic model in the textbook. For over thirty years, the nation has seen little to no GDP growth, a shrinking population, persistent deflation, and enough government debt to make a bond trader faint. Yet, nothing has imploded. The world’s third-largest economy just keeps humming along; quietly, efficiently, and, dare we say, with remarkable poise.

So, here’s the billion-yen question: is Japan’s stagnation a sustainable post-growth equilibrium—something other countries might envy rather than fear—or is this just a polite economic implosion in slow motion hiding behind a facade of civil smiles and punctual trains?

Let’s rewind. The story begins in the early 1990s with the bursting of Japan’s infamous asset bubble, ushering in what economists call the “Lost Decade.” Fast forward, and the singular “decade” is still going steadily after thirty years. GDP growth has flatlined, inflation has barely twitched, and the Bank of Japan has been on a monetary bender that would make even the Fed blush—zero interest rates, massive bond-buying sprees, and even negative rates (yes, they paid people to borrow). It wasn’t until March 2024 that the BOJ finally ended its negative interest rate policy as the rest of the world raised rates to fight inflation (WEF).

Fig. 1: GDP growth and inflation flatlining in Japan (source: World Development Indicators)

Yet, despite all that stagnation, Japan doesn’t look half-bad. According to the New York Times, the economy grew by 1.9% last year—not impressive, but not disastrous. The yen is weak, but exports have held up. Social cohesion remains high. Unemployment is low. The trains are on time. The vending machines are fully stocked. The chaos many predicted back in the ‘90s seemingly never broke out. However, the cracks are there if you look. Japan’s population is not just aging; it’s shrinking, and it’s shrinking fast. The country hit peak population in 2008 and has been in demographic decline ever since. A Reuters survey released earlier this year showed that over 50% of Japanese firms face labor shortages, with one-third calling the situation “serious.” Add in a rigid immigration system and a deeply entrenched work culture, and you’ve got a labor crunch that no amount of automation can easily fix.

However, there’s a counterpoint, and it’s compelling. Despite low growth, Japan still offers its citizens high life expectancy, reliable healthcare, efficient infrastructure, and an enviable level of public safety. Tokyo remains a global capital of innovation and culture. In robotics and automation, Japan is still leading the charge, compensating its labor shortfall with technological muscle. As climate anxiety and post-pandemic exhaustion push more economists to question the “grow or die” mantra, Japan’s model starts to look a little… zen. This is the “equilibrium” argument: Japan has opted out of the GDP rat race and chosen stability over speed. After all, what’s the point of endless growth if people are stressed, infrastructure is crumbling, and the planet is boiling? Maybe Japan isn’t failing, but rather just playing a different game.

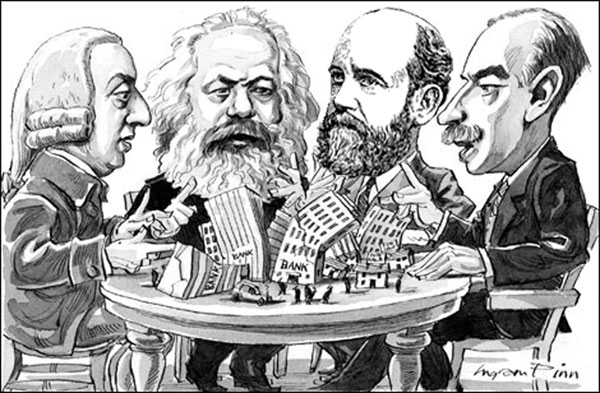

Graphic By: Noam Tal

Before we all start writing haikus about post-growth capitalism, let us talk about debt. Japan’s government debt is a staggering 260% of GDP, the highest among developed economies by a healthy margin. Thanks to low interest rates and high domestic demand for bonds, Japan can manage this current debt, but even the most patient bondholder might flinch if inflation creeps higher. A recent St. Louis Fed analysis notes that if rates rise meaningfully, the cost of servicing Japan’s debt could spiral, forcing painful fiscal decisions. So far, Japan’s central bank has danced this tightrope with surprising grace—but gravity always wins eventually.

Beyond the debt, Japan also faces a risk of global irrelevance. While countries like India, Vietnam, and Indonesia race forward with youthful populations and expanding economies, Japan’s domestic market shrinks, its currency weakens, and its international influence wanes. A Deloitte outlook warns that unless Japan boosts productivity and labor participation, it could slowly fade from global economic leadership, not with a bang, but with a quiet, polite bow. On top of this, there’s a generational toll. Many young Japanese are opting out of marriage and parenthood, discouraged by stagnant wages and rising costs, amidst social expectations often regarded as out of touch. The result? Fewer children, fewer workers, and thereby fewer taxpayers—a vicious cycle that gets harder to break with every passing year.

So which is it; a sustainable post-growth society or a ticking demographic time bomb? The frustrating answer is… both. Japan has shown that an economy can function, and even thrive in some ways, without high growth. However, that equilibrium requires constant balancing. The moment the country stops actively managing its debt, demographics, and productivity, the entire house of cards could start to wobble.

Japan offers both a blueprint and a warning for other countries, especially those with quickly aging populations. It proves breakneck growth isn’t a prerequisite to maintain high living standards, but also that ignoring structural issues only works for so long. South Korea, Germany, and even the U.S. are staring down similar demographic cliffs. The question is no longer if growth will slow, but how countries will handle it when it does. Japan may not have mastered stagnation, but it’s learned how to survive it—gracefully, quietly, and with a surprisingly intact vending machine network. It challenges us to rethink what economic success means in the 21st century. Is it attaining higher quarterly earnings? Or is it a healthy, stable society where people live long lives and don’t fear losing their job every time the stock market dips?

Unfortunately, even the calmest equilibrium can’t rest forever. Japan may be the first to confront the end of growth, but it won’t be the last. Whether it ends in balance or breakdown will depend on Japan’s ability to adapt fast enough to the slowdown it’s been forced to navigate. The world will be watching, deciding whether the outcome will be a precedent, a lesson, or an omen.