JENNIFER JACKSON – MARCH 3RD, 2021

EDITOR: KAT XIE

On January 14, amidst economic and social turmoil, incoming President Joe Biden announced a $1.9 trillion stimulus package as a lifeline for working class Americans, small business owners, and families. The stimulus package includes extending unemployment relief, nutrition assistance, housing assistance, and tax-credits for families and workers. While policymakers from both sides of the aisle have coalesced around the popularity of the package (A CNBC Poll from February 3rd found nearly 70% of Americans support President Biden’s $1.9 trillion Coronavirus relief package), Democrats still struggle to win enough Republican votes on the House floor. Activists following the Biden stimulus plan are pushing for a key, yet contentious, element of the plan: increasing the federal minimum wage to $15 per hour.

There are many reasons why the idea of a $15 minimum wage has been strongly opposed by policymakers and neoclassical economists, despite having widespread support from activists and in the polls. For reference, outside groups have exerted pressure on both progressive and moderate Democrats to increase the minimum wage, where it has stood at $7.25 per hour since 2009.

Essentially, the two foes against the $15 minimum wage lie in the potential disemployment and price effects. Neoclassical economists have predicted that raising the minimum wage would increase unemployment, as firms become more thrifty and lay off workers (disemployment effect). Second, neoclassical economists would predict price increases as firms sought to regain back their profits after paying workers a higher wage (price effects).

The effects of a minimum wage increase on labor markets has been studied in past economic literature extensively, and there is evidence to support claims for and against the $15 minimum wage. Some economists, such as (Reich, et al. 2016) have estimated with confidence that the $15 will not result in huge job losses. While others such as (Evan and Macpherson, 2017) have starker findings: their model estimated that for each 10% increase in the California minimum wage, their findings implied that would reduce employment for all employees by 2%. A study by Purdue University in 2015 suggested that paying fast-food restaurant workers $15 per hour would lead to higher prices. Prices at those businesses could increase by approximately 4.3% according to the study.

What is important to note in the context of the minimum wage increase is that not even economists have a final answer on whether or not raising the minimum wage to $15 will have a profoundly negative or positive impact. First, the evidence on the disemployment effects are heavily contested, and there are studies that find negligible impacts in the United States and European countries. Second, the literature has suggested that minimum wage increases reduce employment for the least skilled workers who tend to be young or early in their careers. Third, economists know a lot less about adopting a much higher minimum wage, such as $15. Finally, there is a great deal of uncertainty about the employment effects of a $15 minimum wage, especially when factoring in the COVID-19 pandemic and the disruptions in public health and consumer behavior.

But one thing that economists do know is that increasing the minimum wage would impact millions more workers than the current minimum wage, including in lower-wage states. As economist David Neumark concluded, “There are two kinds of changes in minimum wages about which we know a lot less. The first change is the adoption of much higher minimum wages—as is happening in the United States with serious movement towards a $15 minimum.” Neumark has cautioned that the costs of a much higher minimum wage are “likely to be understated” by simply scaling up the effects of a minimum wage, based on employment elasticities in existing literature, Neumark has argued that estimating effects based on previous studies of minimum wage, (such as raising the minimum wage to say $10), cannot be generalized to the $15 federal minimum wage increase.

Moreover, in 2014, the CBO issued a report, “The Effects of a Minimum-wage Increase on Employment and Family Income” that indicated that raising the minimum wage to $10.10 would lead to a reduction of approximately 500,000 workers in the labor market. However, 16.5 million low-wage workers would see substantial gains in the earnings in a given week.

Policymakers such as Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) have opposed a national minimum wage of $15 per hour. Senator Manchin is a key centrist figure in the battle for a $15 federal minimum wage and a crucial swing vote. Senator Manchin has suggested that the minimum wage increase to $11 per hour, which he noted was more “appropriate” for West Virginia. As policymakers, federal agencies, outside groups, and economists debate over what is considered too high of a hike, versus not enough, there are many myths as to why we should increase the minimum wage in the first place.

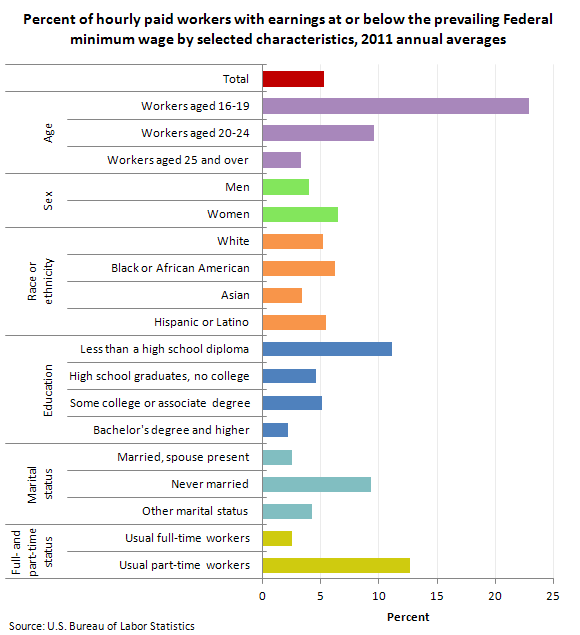

Beyond the political framing and ideological debates within neoclassical economics, let us first examine the characteristics of the average “minimum wage earner” from the perspective of the BLS (Bureau of Labor Statistics.)

Image source: BLS.GOV

Image source: BLS.GOV

The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported in 2015 that “Minimum wage workers tend to be young. Although workers under age 25 represented only about one-fifth of hourly paid workers, they made up about half of those paid the federal minimum wage or less. Among employed teenagers (ages 16 to 19) paid by the hour, about 11% earned the minimum wage or less, compared with about 2% of workers aged 25 and older.”

At the macro level, any substantial increase in the federal minimum wage is likely to have widespread effects on the labor force. Some estimate that as high as 30% of the workforce will have wages boosted in the “ripple effect” of minimum wage increases. Moreover, the CBO (Congressional Budget Office) issued a report “The Effects on Employment and Family Income of Increasing the Federal Minimum Wage” (2019) that bolstered the credibility of the ripple effect. The report found that increasing the minimum wage to $15 would “boost the wages of 17 million workers who would otherwise earn less than $15 per hour.” In addition, approximately 10 million workers earning slightly more than $15 per hour might see their wages rise as well.” The CBO’s median estimate does include that 1.3 million other workers would become jobless (and there is a 66% chance that the change in employment would be between 0 and 3.7 Million workers), while the number of people living below the poverty threshold in 2025, would fall by 1.3 million. Of course, this study was conducted before the vitriolic impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic, yet the larger patterns remain. Boosting the minimum wage comes with tradeoffs, yet has significant and undeniable impacts on millions of workers, including “ripple effects” that impact the rest of the labor force.

It is worthy to keep in mind that beneath the political fiasco and arguments on both sides of the aisle, the $15 minimum wage debate ultimately addresses a fragmentation between neoclassical economics, and its emphasis on growth in aggregate income and what is good for the economy as a whole, versus progressive economics as seen with John Maynard Keynes and the New Deal, with an emphasis on fairness and a “living wage.” (A living wage in 2020 in the United States, would be $16.54 per hour, or $68,808 annually in 2019, for a family of four based on the 2020 Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) poverty guidelines of 2020. ) Scholarly debates over the minimum wage have taken distinct shape over the past three decades—see Princeton’s Alan Krueger and David Card or UC Berkeley’s Emmanual Saez and Thomas Piketty’s work on Capital in the Twenty-First Century.

While there are some truths that forcing businesses to pay workers more would lead to higher unemployment, there are significant benefits that are beyond the scope of national income. Increasing the minimum wage would combat pay inequality (especially based on race and gender) and would drive up consumer spending. Pay inequality would be reduced by raising the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour because it would disproportionately affect women and racial minorities. For instance, raising the minimum wage to $15 an hour would affect 57.9% of women workers and 16.9% of Black workers. However, women only make up 48.5% and Blacks 11.8% of the total U.S. workforce. Given these benefits, and the economic havoc wreaked after COVID-19, the fight for a $15 minimum wage may guarantee economic security rather than cause doomsday price increases and economic fraught, and with all this in mind, perhaps it is time for the minimum wage debate to break up with neoclassical economics.

Featured image source: Scott Olson (Getty Images)

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.