APRIL 24, 2023

Nicolas Depetris Chauvin is a visiting professor at UC Berkeley who is currently the Professor of International Economics at the Geneva School of Business Administration. Hailing from Argentina, he has significant experience working in international economic institutions such as the World Bank and conducting research therein, as well as on economic policy in developing nations in countries such as Ghana.

Q: Thanks so much for taking the time to join us – we want to start by asking about your roots: it’s a standard question but what drew you to become an economist in the first place and to go into academia with a focus in developmental economics specifically?

A: Well, I’m from Argentina *laughs* – that explains a lot. I saw a lot of developmental economics problems and when I was a kid I was obsessed with economics problems but had a very naive style of analysis. I remember under one government there were 12-13 general strikes in the country and as a kid I’d say “they want more money, why not just print more money? That’s it!” Very typical of kids – or for instance when I was a teen I lived through 2 periods of hyperinflation which was quite interesting – my father would get his salary for the week, run to the supermarket and buy as much as he could because the next day it would be double the price. When I was a kid it was cool to wear Reeboks, which was an imported good. So I’d save money from my summer jobs, went to the store to try and buy them but it was closed due to the ‘lack of prices’. I had no idea what that meant or how it indicated that they had no idea how much it would even cost to bring another product into the store due to the inflation. These are things that you face every day when living in a poor country and they influence your thinking, have you wondering if this is normal or not.

So I was going through that, and at the same time in school I was good at math and science but also history, so I talked to my history teacher and she said “choose economics.” I fell in love with the economic way of thinking, did my masters in Argentina which doesn’t have the super-awesome facilities we have in the States so I decided to study abroad – had to study English – took the exams and was admitted, which I’m very grateful for. The US is a bit like the NBA of academics where all the best professors and foreigners teach, European, Asian or otherwise. Then when I went to Princeton I studied macroeconomics which was pertinent to a lot of the situations in my country – inflation, debt, general strikes and a little bit of finance which was quite far from my initial ideas on what I wanted to study.

After my thesis which was on debt relief in poor countries (a movement in the early 2000s which gained a lot of publicity as people like Bono promoted it) I realised that in most of these countries debt problems were not the cause of the country’s problems as much as a symptom of macroeconomic conditions that weren’t going well. In a lot of said countries goverment doesn’t work well, there are sectors of society excluded from economic activity or the markets in key industries like agriculture don’t function. So I did a lot of that at Princeton and most of my work besides debt relief has been on how trade can help countries. From that point on I have spent my life and dedicated it 100% to academia, primarily in internationalization and government work.

Q: While looking over some of your previous work we actually did see that paper about debt relief and how you don’t think it’s a particularly effective method for reducing poverty. When it comes to debt relief it’s particularly popular in rich countries, partly because it’s very easy to understand and make into an ad campaign. Do you think there’s a policy that rich countries who do want to focus on development aid and equitable development can implement that is both easy to sell to the general public and also very effective from a poverty reduction and general development standpoint.

A: Easy to sell? There’s nothing completely easy since taxpayer money is always used to do something like that. The debt relief movement started in 2000s which was the Jubilee, the new millennium and a lot of people were swept up in that excitement, plus some of this debt actually was unfair in many cases and people felt like reducing debt stocks would grant these countries a new opportunity to grow and develop to achieve the then-new UN goals. Everything was in the right place to ‘sell’ this: both activists and the government wanted this, the government because a lot of this debt was probably never going to be collected on or the country would simply take out new loans to pay its debts. As for the activists, a lot of people said it was going to be good for the country, and it makes sense on an intuitive level as a feel-good policy but there was no paper addressing this with empirical methods as something that was actually effective. I realised from that that there was no data on debt relief, so I moved to Washington D.C for 1 year and worked on a professor on a paper that showed that while debt relief can be useful and a good start, it won’t solve the debt problem of a country or the systemic problems that led there and have more impact on the debt level of a country. This also means that if you stop giving aid to a country with the excuse that one has already given debt relief it might make things worse.

The thing about low-income countries is they don’t have strong government or institutions, so even if part of the ‘deal’ with debt relief is that they use the money on healthcare and education development, a lot of times the country does not prefer to do that even when the fiscal space is freed up after debt relief. A lot don’t have the knowledge on how to deploy those resources efficiently and what we showed in that paper was that countries which received the relief didn’t do much better than countries which didn’t receive relief when it came to spending on education and healthcare. I like the idea but in practice, debt relief doesn’t have a great effect, and I think we’ve seen the results of this 10-20 years after those policies. Countries that had their debt levels cut are not doing much better than they were before, so the fiscal space created by the debt relief allowed them to borrow more without necessarily growing faster than countries which didn’t receive debt relief, even though it was palatable to the public for political reasons

Q: You touched on ‘political reasons’ there and it does link back to a question that we wanted to ask you as someone who’s worked with the World Bank previously. So when you talk about world-spanning financial institutions like this and developing countries, there’s a lot of resentment and public hatred stoked toward institutions like the World Bank and IMF since it’s convenient for populists to spread those sentiments – do you have any thoughts on how they can recover their image issue, so to speak?

A: I mean those institutions have made some mistakes, of course, even if they are used as a battle cause by some politicians. I remember applying for a job at the IMF after completing my PhD and the interviewer asked me “You’re from Argentina, why do you want to work for the IMF?” Even so it’s not easy, even for those with good wishes to be in the position of the IMF and work in internalization from Washington DC or Geneva without going to a country, it’s hard to understand reality without being on the ground there. Of course, developing countries, typically those helped by the World Bank will usually have a liaison office outside of the country that will fill in the knowledge gaps to put together a solution, but it is still very hard. Even if you’re in academia, without traveling to the country it’s very hard to gather a solution since what’s written in the book is not the reality in the field. Heterogeneity matters, and a lot of our models think about perfect markets, which are not exactly abundant in these types of developing countries.

Q: As someone heavily involved in the field, do you feel that developmental economics has gained significant amounts of recognition over the last decade or so? From the outside, we can look at events like the 2019 Nobel Prize being awarded to developmental economists, as well as the recent rapid growth of economies like Botswana and Rwanda as a positive sign for the acceptance of developmental economic theory by world governments, but do you feel differently at all?

A: Now there’s more evidence-based policy and now we can collect data, vet it and use better evidence-gathering tools than previous which are attuned to the unique situation of a country, which definitely helps us. The key to good studies like we’re conducting now is experimental analysis – something I’m not a big fan of but has become very common. You go to the field with an experiment to run, randomly select participants to whom you apply a treatment to a subset of then investigate the difference in outcome between the two groups to see whether or not a policy worked. In Ghana, where I lived for a few years, we advised companies on how to export to developed countries with higher consumer power using the best practices from a quality control and marketing/management/logistics perspective. We shared experiences that were successful and compared the results of businesses who did get the consulting services with those who didn’t after a year of data collection, for example.

These days we take better care of how we analyze the data as well, in order to have more scientifically-based policies. In the 50s and 60s this was basically ideology – capitalism vs socialism/communism and now we look more towards the conditions of the economy or a specific sector and understand well the constraints that exist within it and the limits to cultural/social growth, since the same policy won’t apply to everybody the same way, obviously. If you look at the data, the amount of people who live under poverty today is much lower than previously, and life expectancy is much much higher than it was 50 years ago, and we should take pride in that as a sign of policies improving conditions.

When many countries remain being poorly developed there’s usually some constraint that keeps them from participating in free trade – insufficient infrastructure, skills – and it keeps them in the middle-income trap. Countries like Chile, Costa Rica, China have grown consistently but are now at a level of real GDP where they are not growing like they used to be and have problems fully upgrading to a developed country. They either have problems that we haven’t fully identified yet or that we know of but don’t know how to solve, and I think developmental economics can help countries like that most of all, along with poor people in rich countries – in short, the work is not done. While economists cannot keep a country from making mistakes, they can keep them on the right track, and we have made a lot of progress.

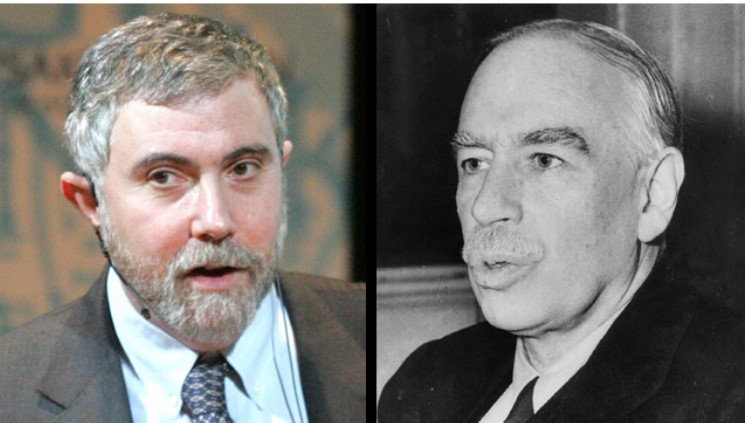

Featured Image Source: Trade and Labor Market Outcomes in Developing Countries

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.