RAINA ZHAO – NOVEMBER 7TH, 2019 EDITOR: ODYSSEUS PYRINIS

Education is a cornerstone of the American Dream. For many, a college education is paramount to upward mobility. In the United States, professionals possessing a bachelor’s degree typically earn 66% more than those with only a high school diploma, and 75% of the fastest-growing occupations necessitate a college degree.

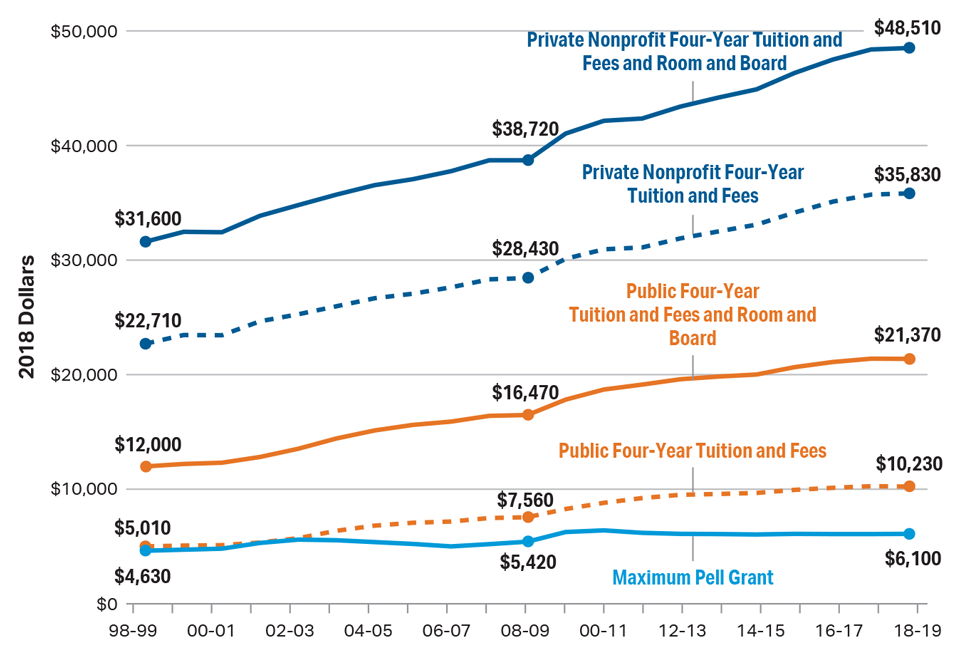

However, as the cost of attending college escalates, this traditionally low-risk path to prosperity is becoming impossible to reach for more and more Americans. Since 1989, the cost of attending a private non-profit university has more than doubled, while the fees for an average four-year public university have tripled. In 2017, the Institute for Higher Education Policy reported that 95% of colleges in the United States were unaffordable for 8 out of 10 students. In 2015, a whopping 83% of Americans said they could not afford to go to college.

While the inaccessibility of college continues to escalate, experts still cannot agree on the exact causes of this trend. Studies indicate many different possible drivers of increasing tuition costs. For one, state investment in higher education has declined, which has been shown to raise tuition at an increasing rate. Others have different ideas.

In 1984, then-Secretary of Education William Bennett published “Our Greedy Colleges” in the New York Times. Now infamously known as the Bennett Hypothesis, the article argued that expansions of student financial aid were the true culprits of increasing the cost of attending college. “If anything,” Bennett wrote, “increases in financial aid in recent years have enabled colleges and universities blithely to raise their tuitions, confident that Federal loan subsidies would help cushion the increase.”

The Bennett Hypothesis has since then been a contentious topic among higher education policy analysts and academics. A 2015 study from the New York Federal Reserve supported the Hypothesis, concluding that increases in Pell Grant and federal student loans strongly corresponded with increases in the cost of attending college. The analysis found that for every dollar increase in the federal subsidized loan maximum, the cost of attending college increased by 60 cents, and for every dollar increase in the Pell Grant maximum, college tuition increased by 37 cents.

However, the Federal Reserve study was far from the end of the debate. The correlation found in the study was most prevalent when it concerned expensive, for-profit universities with relatively low selectivity. An American Council on Education report found that selective private institutions generally priced their tuition according to the willingness to pay of the wealthiest families in attendance—a group that is “largely unaffected by changes in federal aid policy.” The same study concluded that public colleges were more susceptible to changing their tuition based on financial aid, but costs remained largely dependent on state politics and investment.

The Center for American Progress showed that college tuition increased even when student loan limits stayed constant; from 1995 to 2014, the maximum loan limit only increased twice, while tuition increased every year. Other research has found little to no relationship between increases in financial aid and increases in tuition for professional graduate school. On the other hand, a University of Oregon study found that the Bennett Hypothesis could not be observed among public or lower-ranked universities, but found a strong relationship when it came to prestigious private universities. It is little wonder that a literature review by the bipartisan Congressional Research Service came to the conclusion that there were too many contradictory findings, not only between different studies, but also within single studies. The report ultimately argued that it was not plausible to say college fees would not have increased in the absence of increases in financial aid.

Clearly, the relationship between financial aid and the rising cost of attending college is hotly contested. However, the debate has far-reaching impact on policy-making, particularly during the past two years. In 2018, Secretary of Education Betsy Devos claimed the United States was in the middle of a “crisis” and cited the Bennett Hypothesis, stating “It has something to do with what one of my predecessors famously pointed out decades ago. When the federal government loans more taxpayer money, schools raise their rates.” Concurrently, President Trump’s budget for the 2019 fiscal year eliminated some federal student loan programs, including subsidized loans. His 2020 budget proposal would slash higher education funding.

According to both Devos’ and Bennett’s logic, decreasing government spending on financial aid will drive down college tuition fees. However, it is important to consider the short-term effects of cutting student aid and whom the cuts would most affect. Currently, middle-class students who do not meet the threshold to receive more generous grant aid packages (and thus must take out more loans) shoulder the biggest burden when it comes to student debt. Dartmouth sociology professor Jason N. Houle found that students from families earning between $40,000 to $59,000 in annual income took on 60% more debt in comparison to lower-income students, and 280% more than students from families earning between $100,000 to $149,000 in annual income. As students graduate, the makeup of debt-holders shifts. In households aged 25 or older, the highest income quartile actually holds the highest share of debt. It is also worth noting that loan repayments are significantly more difficult for low-wealth households, even if their income is high. Considering the wealth disparity between ethnic groups, this means that student debt disproportionately affects Black and Latinx debt holders.

In contrast, Pell Grant recipients must come from families making $50,000 or less to qualify. The majority of Pell Grant recipients come from families with annual incomes under $20,000. Short-term rollbacks on Pell Grant aid would affect the population of students who most lack access to higher education. While the price of college has increasingly skyrocketed, the maximum Pell Grant allowed has increased at a much lower rate. Cutting grant aid would eliminate a significant fraction of an already small sum, at least relative to the full cost of college.

Image source: College Board

Furthermore, if the maximum Pell Grant disbursement falls, students once eligible for the grant may find themselves taking out more loans to pay for college. Currently, the Pell Grant only covers a fraction of the full cost of attending college. Since the 1970s, the purchasing power of the Pell Grant has fallen from 67% to 27% of the average cost of attending college. Lowering the Pell Grant would mean that students who could not afford college before the Pell Grant would face increased pressures of student debt, which may be exacerbated if they also come from a low-wealth family.

Even if rolling back financial aid programs results in downward pressure on college tuition in the long run, reducing student aid has significant short-term implications for college accessibility, whether it is in the form of limiting flexibility and ability to repay loans or reducing grant aid.

Featured Image: US News

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.