SARA BETTS – MARCH 18, 2022

EDITOR: ATMAN MOHANTY

“We used the land. We hadn’t tested and analyzed the soil. We planted things and they grew. We hadn’t run a feasibility study. We had enough labor, freely given, to build the Park. We had no budgets. We found the money and materials we needed in our community. We had no organization, no leader, no committee. The Park was built by anyone and everyone and we, all of us together, worked it out.”

– Alan Copeland, activist and editor of People’s Park: Photographs of the Struggle for People’s Park in Berkeley

Public space is sacred. For thousands of years, people have used public space to foster community and creativity, share ideas and passions, and come together in harmony. People’s Park, founded in April 1969, is located in the City of Berkeley, just a few blocks south of the University campus. Per its website, People’s Park is a gathering place for community, history, free speech, social justice, civil rights, gardens, music, education, recreation, ecology, sports, and more. The park was built from no more than a muddy lot and the strength of human connection. Prior to then, the University (henceforth referred to as UCB) bought and bulldozed the homes that once stood there, which some claim was an effort to disperse the young activists that lived there. On May 15, 1969 – mere weeks after the park was created – Bloody Thursday set the narrative for the contention that surrounds the park to this day. Fifty-eight people were hospitalized by the end of a day that began as a protest against UCB’s seizure of the park. Demonstrators were shot at and tear-gassed by police, and soon after, a fence was erected around People’s Park.

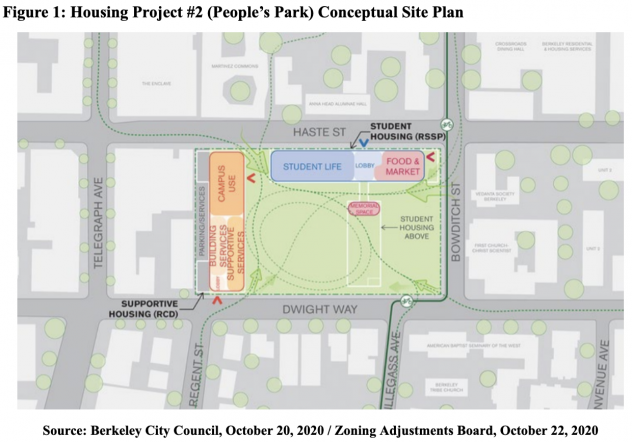

Today, People’s Park is home to dozens of unhoused people. While the park’s community looks different than in 1969, it is a community nonetheless. Last year, UCB’s Chancellor Carol Christ announced plans to build student housing in People’s Park. Titled Housing Project #2, these plans will effectively displace unhoused people in a move that is symbolic of the end of the free speech, camaraderie, and revolution that once defined Berkeley. UCB has claimed that it will rehome some of the park’s current residents in permanent supportive housing. According to UCB, the supportive housing at People’s Park will be a separate building from the student housing and will include approximately 100 apartments. However, the units will cost between $400 and $1400 per month, which is outrageously unaffordable for the park’s current residents. The significance of where UCB is choosing to build the housing does not go unnoticed. As of 2016, UCB is the largest land-holding university in California, and has had access to federal funds and an endowment in the several billions of dollars has helped it to expand. UCB’s share of the Morrill Land-Grant Act alone was 150,000 acres.

The Save People’s Park website reads, “[UCB is] planning to build 1,000 units of market-rate student housing on the People’s Park site. The UC has nine other sites to build on, but they bear an old grudge against the park […] Potential conflict between homeless residents and students packed tightly together seems a likely, if not inevitable, possibility. Who do you think will lose that battle?”

I interviewed Joe Liesner, a lifelong activist and key player in the movement to save People’s Park, to find out how he feels about UCB’s plan for the park. He described People’s Park as “a monument to the people in the 1960s who stood up for justice and peace,” and a current-day “refuge for poor people and people of color.” He described UCB as “part of the status quo.” When asked about the plans for supportive housing, he asked, “How will the ‘preservation’ of half of People’s Park exist? The images of the plan show students laying on the lawn. There are no tables or benches. This isn’t about helping people. The people that are marginalized – those people will have no place to sit down, take a load off their back, and relax in a place that has the healing power of nature.”

Liesner and his cohorts in the People’s Park Historic District Advocacy Group have moved forward with a nomination to classify the park as a historic landmark. An excerpt from the petition states, “The People’s Park Stage was the subject of a lawsuit in 1987 with Alameda County Superior Court Judge Henry Ramsey ruling in favor of the People’s Park Council, a ruling that ‘established and recognized the status of People’s park as a ‘quintessential public forum’ for freedom of speech, assembly and public expression.’ The ruling, which remains in effect today, requires [UCB] to permit amplified sound. The Court ordered [UCB] as defendant in the lawsuit, to cooperate with and facilitate the plaintiffs in scheduling and conducting public amplified events specifically on the People’s Park Stage. […] The stage area is often used for memorials and food distribution by various nonprofit groups dedicated to addressing community needs, a tradition which is as old as the park itself.” Unfortunately, however, the registration of People’s Park as a federally recognized historic place will not disallow its destruction. The People’s Park Historic District Advocacy Group hopes to delay the plan with their lawsuit against UCB’s 2021 Long Range Development Plan (LRDP) on the grounds that its Environmental Impact Report is biased and inaccurate.

Liesner articulated something that resonated deeply with me when he said, “Democracy is not just threatened – it has been crippled.”

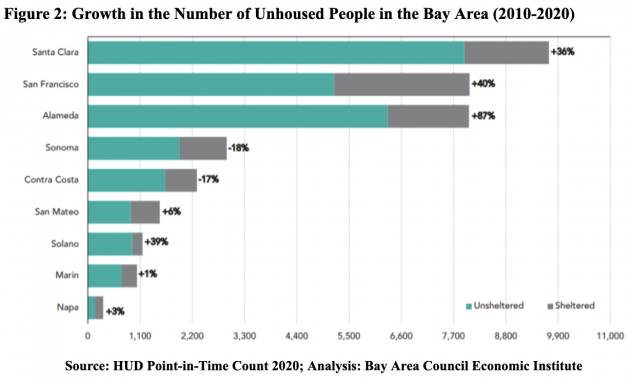

A study and subsequent report by the Bay Area Council’s Economic Institute found that the Bay Area had an estimated 35,118 unhoused individuals in 2020, the third-highest of any region in the United States. The Bay Area’s unhoused population is also growing faster than the general population. In Alameda County alone, the percentage of unhoused people has exploded by 87% in the period between 2010 and 2020 (shown in Figure 2 below).

As of 2019, there were over 1,000 unhoused people in the City of Berkeley. There has been no official city count since the beginning of the Coronavirus pandemic, but due to its socio-economic implications, I feel it is safe to say that number has increased.

Housing Project #2 will be funded by bonds and is set to cost a mere $312,047. The site will provide between 950 and 1,200 student beds, making it extraordinarily lucrative in the long run. Perhaps that is why it is such an enticing project. However, as of 2020, UCB had over $8,843,106 in total assets and an end-of-year net position of $2,329,650. It held $7,311,484 in capital assets (at original cost), which includes land, infrastructure, buildings and improvements, equipment, software, intangibles, libraries and collections, special collections, and construction in progress. It received $3,386,457 in total endowments and gifts. Simply put, UCB is not hurting for resources.

A 26-member Board of Regents governs UCB, 18 of whom are appointed by the Governor and approved by a majority vote of the State Senate (currently for a 12-year term), one student Regent, who is appointed by the board to a one-year period, and seven ex officio Regents who are members of the board under their elective or appointed positions. Since the government instates the majority of Regents, the issue of People’s Park is a democratic concern.

The University of California is well-endowed with financial resources. For example, the University of California system’s payroll totaled over $18 billion for 2020, and total employee benefits (which include health, dental, vision, and retirement) were over $3.5 billion in 2020. However, UCB relied on private investors, government funding, and other sources of support to raise $99 million for its Capital Campaign, a philanthropic endeavor it undertook from 2015 through 2020. This money, which was raised over a period of five years, was just 0.46 percent of the money spent on its employees in 2020 alone. Further, for the 2021-2022 period, the Regents were granted a portion of Limited Project Revenue Bonds in the (approximate) amount of $1,228,338,000 to be used to finance or refinance projects on all eight of the University of California campuses. The Regents can also use the funds for any additional projects they authorize, leaving no need for checks and balances. UCB could easily cover the $4,800 to $16,800 in yearly rent for the 100 proposed apartments in its supportive housing plan and far more. Since this is the case, the decision to build student housing on People’s Park is wholly unnecessary, as UCB has the opportunity to augment student housing nearly wherever it would like.

The rich history of People’s Park does not deserve to be erased. There is so much more at stake than student housing – this is a humanitarian crisis. The dozens of people who call the park home are at risk, and it would be a disservice to our community to allow their displacement. The truth of the matter is this: UCB has the opportunity to use its access to resources as a driving force to ensure the preservation of People’s Park. In the words of Mario Savio, the infamous leader of Berkeley’s Free Speech Movement in the 1960s:

“There is a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart, that you can’t take part. You can’t even passively take part. And you’ve got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you’ve got to make it stop. And you’ve got to indicate to the people who run it – to the people who own it – that unless you’re free, the machine will be prevented from working at all.”

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.