ANIKA MIRZA – MARCH 19TH, 2019

In 2017, Americans around the country followed Amazon’s highly dramatized quest for its next headquarters. Starting with two-hundred potential candidates, Amazon quickly narrowed down the list to two: Virginia and New York. However, after months of protest from politicians, activists, and residents, Amazon pulled out of the deal on February 14th.

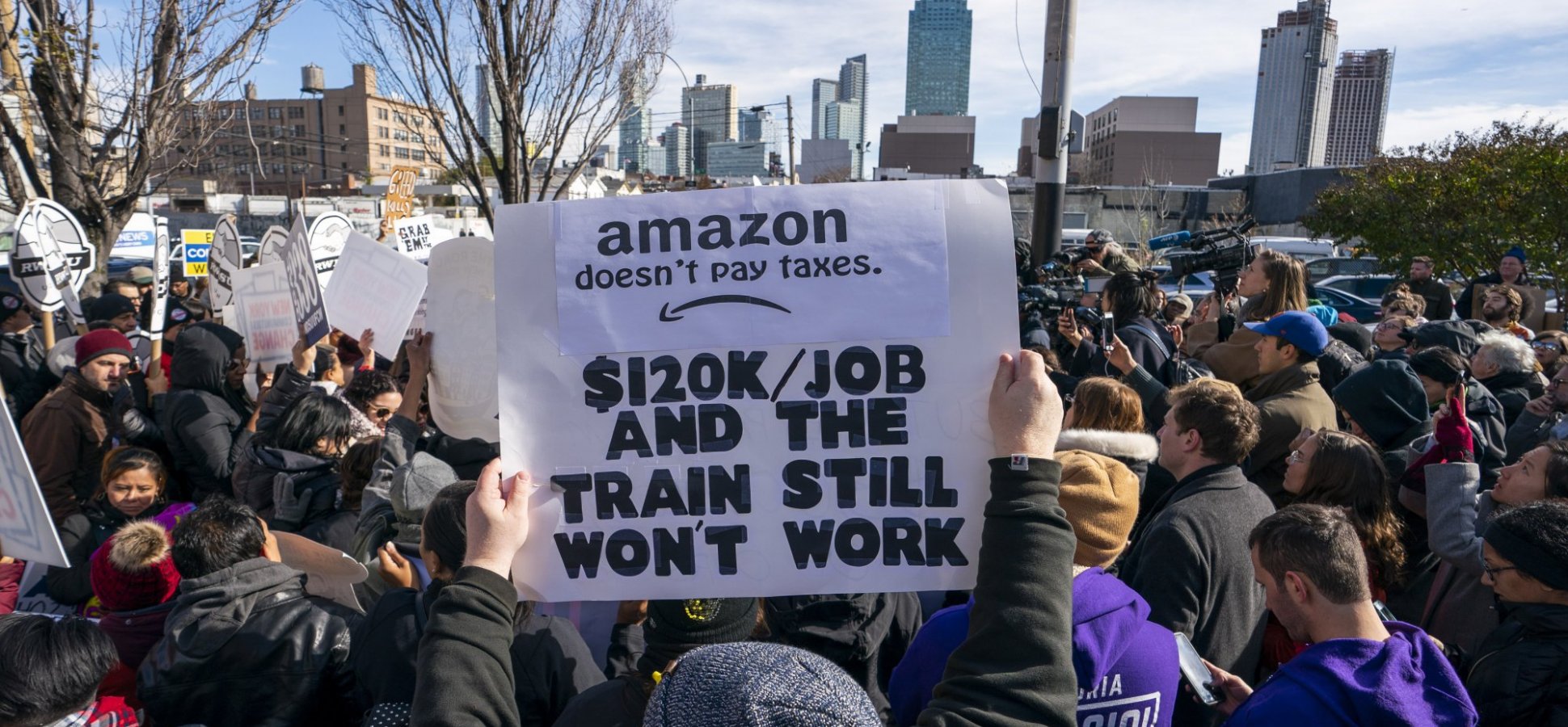

The controversy centered around the $2B corporate subsidy Queens would give Amazon in exchange for 50,000 jobs and the privilege of housing an esteemed company. Attracting companies with money and tax breaks is a fairly common practice. American cities and states shell out $90 billion annually to entice companies like Amazon. Not only is this more money than the federal government allocates towards housing, education, or infrastructure, but also it means states with already strapped budgets are trading off resources from schools, roads, and police to pay mega-rich companies like Amazon. Many people also question whose interests the government officials constructing these deals have in mind. The debate between the very real benefits of jobs and innovation to a city with the equally relevant initial cost and potential of harmful gentrification is one worth having. However, it becomes difficult to have a debate when Amazon requires nondisclosure agreements from all potential ‘Headquarter 2 (HQ2)’ city candidates. Many New Yorkers voiced concern over the lack of transparency surrounding the whole process. Other New Yorkers were not just concerned with the subsidy, but also the long term effect of Amazon in Queens.

Besides the corporate subsidy, not everyone agreed that the money Amazon would bring to New York City would help the average resident. The influx of upper-class, white-collared jobs would likely raise housing prices and burden the city’s public transportation. This is especially problematic in New York City where many reports show demand for affordable housing—and housing, in general—is far outpacing supply. However, under much different economic conditions, Amazon building HQ2 would likely have benefits. For example, in cities with less expensive housing markets, Amazon wouldn’t raise property values to the point that people would be priced out of their homes. Instead, Amazon would encourage innovation and provide jobs to both low and high skilled workers.

Despite the backlash Amazon faced, the company could have genuinely helped the area. Building HQ2 in Queens would have made Amazon a stakeholder there. Amazon could have potentially incentivized investment in public education if only for the self-serving desire to have an educated workforce from which to pull. Amazon may have also invested in housing for residents experiencing homelessness and other affordable housing programs because improving the quality of their workers’ lives improves the productivity of its labor force. However, there is no guarantee Amazon would have done any of this. Many believe that, instead of hoping Amazon acts in the benefit of Queens, the government should directly invest the $2 billion in housing, infrastructure, and transportation for residents.

The Amazon HQ2 issue is more complex than it initially appears. It is more than just a big tech company trying to move into an urban center. It brings up questions about job creation, gentrification, and the relationship between politicians and corporations. The Amazon deal demonstrates that while big companies moving into cities leads to development, that development is not inherently equally distributed.

Featured Image Source: Image Source

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.