ALLY MINTZER – DECEMBER 3RD, 2020

EDITOR: COURTNEY FUNG

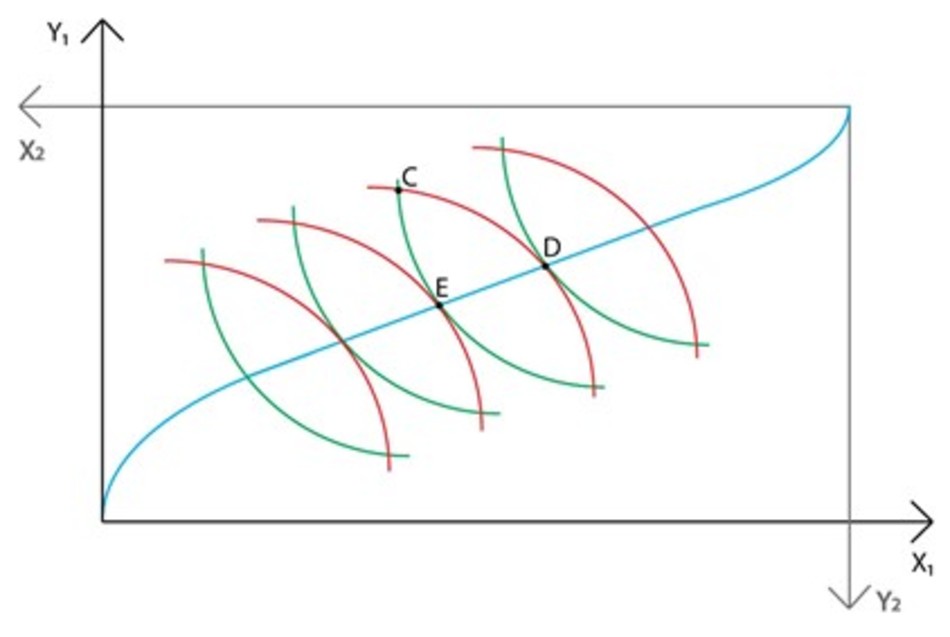

If you have ever taken an introductory economics course, there’s a good chance you learned about Pareto efficiency. If you haven’t—or need a refresher—Pareto efficiency is defined informally as an allocation of resources where someone cannot be made better off without making someone else worse off. Conditions for achieving such an efficiency include having exchange efficiency, where no further trade can be mutually beneficial, and production efficiency, where the reallocation of factors of production (like land or machinery) to make goods cannot be improved.

Seems to make sense; people generally want to avoid making someone else worse off, assuming that most people are constrained by their humanity. However, take the example of an oligopolist who owns an obscene amount of wealth. The state implements a wealth tax and redistributes the revenue to people who are in much greater need of it. Thousands of people benefit greatly from this policy, and only one person is negligibly harmed. However, according to the principle of Pareto efficiency, because one person was harmed despite massive improvement for many, this is not an efficient policy.

In sum, the notion of Pareto efficiency largely ignores equity and distribution. So, how did this principle become the gold standard for efficiency? To understand Pareto efficiency, it’s first important to understand its creator.

Who Was Vilfredo Pareto?

Vilfredo Pareto (1848-1923) was an Italian sociologist by training who later became an economist in his early 40s. Pareto was part of the Lausanne School of Economic Thought, a precursor to neoclassical economics. Pareto succeeded his advisor and fellow Lausanne School founder Leon Walras’s post at the University of Lausanne. Because of its emphasis on mathematics, the Lausanne school was also nicknamed “The Mathematics School.” The most notable feature of this school was its theory on general equilibrium, which included Pareto Efficiency.

It is well-known that Pareto was (allegedly) a fascist, especially with his views on antirationalism, anti-intellectualism, and disdain for democracy. Although he died in 1923 on the eve of Mussolini’s rise to power in Italy, based on his writings, many speculate that he would have been very sympathetic to the advent of fascism, and very few have attempted to prove these theories wrong. According to Pareto, humans are irrational, impulsive, and act without purpose. As James Vander Zanden argued, “The sentiment and instinct glorified by Pareto above all others, as indicative of strength, virility and excellence, was brute force used by an elite as an instrument of gaining and exercising power.” Similarly, Pareto praised political suppression of the general public at the hands of the elite, and believed it was necessary for social stability.

Criticisms of Pareto Efficiency

As aforementioned, Pareto efficiency ignores equity and distribution and implicitly favors the status quo. It biases towards supposed stability, even in the face of mounting inequality.

Assumed within Pareto Efficiency is that one’s utility, or happiness, is derived from one’s own materials. Admittedly, much of our utility is dependent on and influenced by our material possessions in relation to others. Swedish philosopher Sven Ove Hansson notes this in “Welfare, Justice, and Pareto Efficiency,” asserting that a reduction of material inequality is necessary for achieving Pareto efficiency in terms of well-being. Take, for example, our previous oligopolist. Our oligopolist successfully lobbied the government to reduce capital gains taxes, and is now even more obscenely wealthy compared to everyone else. Assuming that most people were not directly harmed, at least on the surface, this new policy would therefore be a Pareto improvement. Yet it is clear that this is far from being fair. Widening inequality hurts all of us by undermining both economic and political systems, and the concept of Pareto efficiency does not take that into account.

Is Pareto Efficiency useful?

Being the gold standard of policy analysis, Pareto Efficiency is a relatively simple way of supposedly solving complex problems without taking fairness into account. As UC Berkeley Law Professor Daniel Farber explains, “While much dispute exists about Kaldor-Hicks efficiency and about the relevance of distributional norms to law and economics, the Pareto principle is often taken by practitioners of law and economics as being beyond controversy.”

Pareto Efficiency, like all economic models, is a way to take the world with all its nuance and complexity and describe it with mathematical expressions and theories. Pareto Optimality, therefore, should not be the sole principle we strive to achieve; fairness and distributive justice must be considered. According to Amartya Sen in Ethics and Economics, “It has been thought reasonable to suppose that the very best state must be at least Pareto optimal.” Pareto Efficiency should be a tool for evaluating economic circumstances, not the end goal.

Featured Image Source: Policonomics

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.