EVAN DAVIS – October 31st, 2022

EDITOR: AAYUSH SINGH

“Socialism… has a record of failure so blatant only an intellectual could ignore or evade it.” – Thomas Sowell

When the Berlin Wall fell and Soviet Russia collapsed, capitalism triumphed over socialism on the global stage. Or… so we thought.

Today, renewed interest in socialism among younger generations has resulted in an upswing in anti-capitalist rhetoric, with politicians such as Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez marketing themselves as socialists and promising more government intervention in the economy. This has resulted in backlash from followers of capitalist thought, with Donald Trump declaring that America will never turn to socialism.

But is socialism even wrong? Arguments against socialism span a wide range of critiques, from the difficulty in its implementation to human selfishness. While these claims concern socialism’s practicality, one argument against socialism pushes a different idea altogether: that even in theory, socialism is untenable: the economic calculation problem (ECP).

What is the ECP?

To understand the ECP, it is first necessary to outline the underlying concept. Economic calculation refers to the ability of businesses and entrepreneurs in a market to use available prices to predict or calculate the net profitability of economic projects by calculating expected profit and loss. As economist Per Bylund covers in his book How to Think About the Economy: A Primer, the goal of a business or entrepreneur is to turn a profit: earn more money from consumers than they spend. Entrepreneurs are the driving forces of change in an economy, as they constantly innovate in ways big and small. Their expected profit is what determines which resources they use up. Higher expected profits mean they expect to generate more value for consumers, and can thus afford to buy more expensive, in-demand, and scarce resources. Lower expected profits mean lower expected value generation, resulting in a constrained ability to use up valuable resources. While entrepreneurs can be mistaken, their correct guesses facilitate a process which drives economic progress, and the price system indirectly allocates resources to where they are expected to produce the most value.

The price system and the resulting system of profit and loss exists because of our market economy. State socialism (socialism without markets) abolishes the market economy as the system of production and distribution of scarce resources, replacing it with a system of centralized planning. The ECP is essentially the issue socialism has with figuring out how to distribute resources between different productive sectors of the economy without market prices, profit, and loss. Consider how a central planner would determine where to distribute wood. How much would go towards production of pencils? How much towards chairs? Tables? Houses? Doors? Firewood? Paper cards? The same problem exists for gasoline, steel, and any other resource in an economy, which goes into direct production of commodities, production of machines used to produce commodities, production of transportation for machines and commodities, etc. As Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises states in his book Socialism, without market prices, “All economic change… would be a leap in the dark. Socialism is the renunciation of rational economy.”

It should be clarified that the ECP applies to a Marxian conception of socialism, involving the abolition of capitalism. Social democracy, the model European countries such as France and Italy follow, and strong traits of which can be observed in places such as Nordic Europe and even the United States, is still broadly capitalism, yet the government involves itself heavily in regulating the economy and providing social services. This is not socialism in a strict sense; the ECP does not apply.

It is also worth noting that this problem applies mainly to centrally planned socialist societies. There exist forms of ‘market socialism’, where competitive markets remain, but hierarchical business models are entirely replaced by co-ops. But the majority of Marxian socialists see market competition as an anarchic issue of unplanned chaos to be solved through central planning.

Empirical Evidence

The ECP in the past has been a verifiable problem in socialist societies. The most notable example was the USSR, the earliest large-scale attempt at a planned socialist economy.

After the Bolsheviks seized power, in 1918 they banned private trade, nationalized almost all industry, and seized control of food products. The pressure of this attempt at planning, combined with the effects of the Russian civil war, destroyed the economy. Trotsky admitted that Russia’s economic collapse “surpassed anything of the kind that history had ever seen,” leaving the country staring into the “abyss.” To rectify this issue, Vladimir Lenin was forced to re-introduce what he’d fought to abolish: markets. His New Economic Policy (NEP) allowed for limited free market trade, and it was able to jump-start the Soviet economy back to pre-war levels.

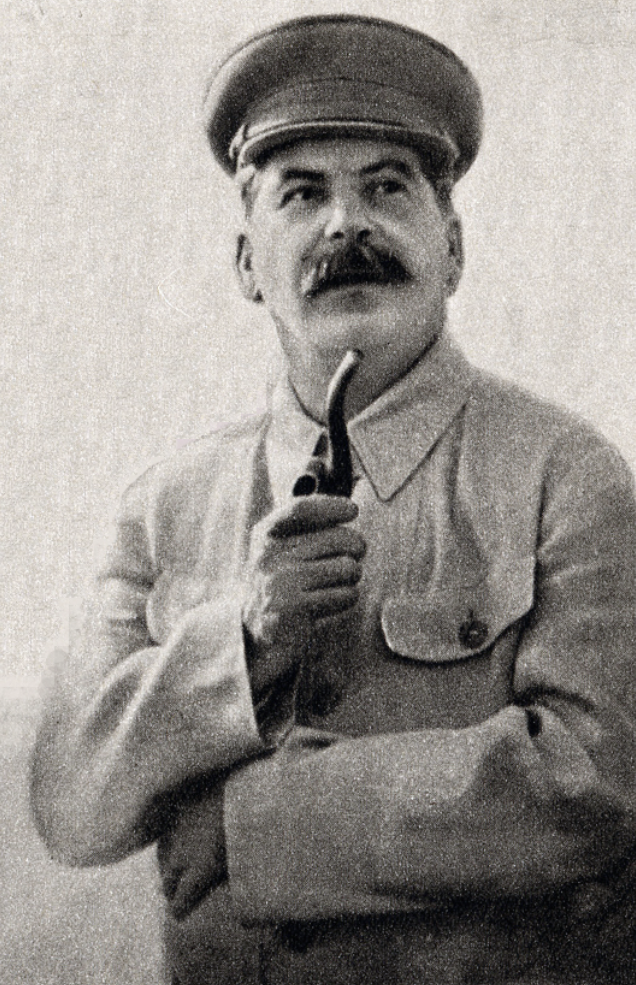

However, in 1929, Lenin’s successor, Joseph Stalin, abolished the NEP. With the reintroduction of a more planned economy, the USSR and socialist societies that followed were left with a problem: they would have to include some sort of non-market “monetary” calculation in their planning models. Economist Paul Cockshott from the University of Glasgow writes, “if there are hundreds of thousands, or perhaps millions, of distinct products, no central planning authority could hope to keep track of them all… by resorting to monetary targets, the socialist economies were already conceding part of Mises’s argument. They were resorting to the monetary calculation that he had declared to be vital to any economic rationality…”

The ECP can be glaringly observed when Stalin outlined an issue where planners had submitted faulty pricing proposals which failed to account for the relative scarcity of cotton and bread to grain, stating, “what would have happened if the proposal of these comrades had received legal force? We should have ruined the cotton growers and would have found ourselves without cotton.” While market prices would account for scarcity as businesses adjust them to maximize profit, the planners in the USSR found themselves grasping blindly for proper prices to set.

Studies have also shown that allocative efficiency (distribution of goods and resources to where they are needed most) in the USSR was very low. According to the 2019 Presidential Economic Report, socialist planning and pricing policy in the USSR – including “excessive centralization of the planning, control, and management of agriculture, inappropriate price policies, and defective incentive systems” – reduced Soviet agricultural output by about 50%. Furthermore, an empirical study on Soviet industry found “low levels of allocative efficiency.” Former Soviet Prime Minister Yegor Gaidar even gives numerous concrete examples of material inefficiency in his book Collapse of an Empire.

Other socialist societies have also attempted to grapple with the ECP, notably socialist Chile. Under Marxian President Salvador Allende, Chile attempted to develop a planning model for the economy known as Project Cybersyn. It was never completed. In the meantime, Allende implemented a transition towards socialism involving “a strategy of income distribution, expansion of government programmes and services, state control of key industries and extension of land reform…” The state mandated higher wages, while prices for goods and services were barred from rising. As a result, goods became scarce, and hyperinflation took place.

Due to the replacement of market allocation mechanisms with socialist policy (as opposed to the empirically refuted explanation of an “invisible blockade”), Chile’s economy continued to worsen. To try to curb hyperinflation, Allende implemented “rationing, price controls, and the nationalization of product distribution,” which led to “massive shortages, hoarding, and queuing.” While Pinochet’s dictatorial regime committed far more human rights violations and had economic problems of its own, Allende’s catastrophic economic mismanagement through planning measures such as rationing and wage and price distortions had destroyed the Chilean economy before a central planning system was even fully implemented.

Further empirical analysis comparing market economies to planned economies as a whole showed that almost all planned economies in the Soviet Bloc were substantially less allocatively efficient than almost all measured market economies. The sole exception was Bulgaria, which was successfully experimenting with markets at the time.

Objections

Despite the evidence, the ECP as an argument has not gone unchallenged. A variety of socialist and non-socialist academics have done their best to attempt to discredit the ECP, either by undermining its foundations or creating planning models which try to circumvent the issue entirely.

One common objection is that capitalism does not achieve complete efficiency: resources are wasted every day. This argument is often put forward by Keynesians, who note that competition is imperfect, markets are disequilibrated, workers are unemployed, and resources are idle. However, as economists Bylund and William Hutt note, complete efficiency cannot be achieved by any economic system, markets included. As long as desires and conditions are in flux, change occurs, and equilibrium shifts, always sought rather than reached. Thus, resources have to shift hands to adjust for the shift in equilibrium, meaning complete efficiency is more of a target to be moved toward than actually hit. Furthermore, leaving resources and labor “idle” allows for long-term investment plans to take fruition, and labor to switch between industries as economic conditions change. This dynamic process is something socialism, to the extent that it lacks market prices, does not share.

Neoclassical economist Bryan Caplan objects that the ECP is not a serious problem for socialism. He argues that other problems were more damaging. It’s true these problems exist. F.A. Hayek’s Knowledge Problem posits that prices convey information about consumer desires, and without prices, this decentralized information isn’t properly distributed. Planning models may simply be computationally intractable, and issues with incentives certainly existed under socialism. However, the ECP is still a fundamental problem which empirically cripples socialism, even if other factors contributed to its downfall.

Socialists such as Cockshott and Jan Dapprich from the University of Glasgow have objected that the ECP is irrelevant, because it’s already been solved through modernized central planning models. These models take available resources in an economy as inputs, and optimize material production of desired outputs, often sold on a market where wages and prices are determined by the state. Production is planned; if distribution isn’t, the market for goods is heavily regulated.

First off, by leaving a market for consumer goods (goods such as food which are immediately consumed), many socialist solutions already concede the inefficiency of planning when it comes to distributing commodities. However, none of these “solutions” to the ECP extend the same considerations to capital goods (resources used for producing other goods). If producers can’t trade capital goods when they could better use other capital goods, production cannot be optimized as economic conditions change. Furthermore, the innovative drive of entrepreneurship is eliminated, as capital goods cannot be traded to be used in entrepreneurial endeavors. The process driving growth under markets is removed, leaving behind the inefficiency that has historically plagued socialist societies which utilized planning models and pre-set plans. It is important to remember this inefficiency. As previously mentioned, the USSR, operating under a series of central plans, was horrifically inefficient despite its planners’ best efforts. What remains to be desired in these solutions is that they don’t imitate a market well enough.

In the future, could theoretical supercomputers, given enough information about the physical world and wired up to people’s brains, successfully simulate their interactions and the resulting market economy (thus overcoming the ECP by perfectly predicting the market economy), before improving upon it to try and maximize human happiness? This near omniscient-level of required accuracy presents a completely unsolvable problem for any society which isn’t both totalitarian and far more technologically capable than ours today. It’s questionable if this solution is even possible, and in such an advanced future society, such planning might not even be strictly necessary if scarcity is effectively abolished beforehand.

Conclusion

In conclusion, does the ECP make a rational implementation of socialism impossible? In a literal sense, no. However, given the inability of today’s advanced technology to successfully simulate and surpass market functions needed for rational economic activity, the ECP remains a serious issue for socialist societies for the foreseeable future. Without it being solved, capitalism will continue to outperform socialism in nearly all cases. As Mises wrote in his magnum opus Human Action, “Socialism is an alternative to capitalism as potassium cyanide is an alternative to water.”

Featured Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.