KATERI MOUAWAD – FEBRUARY 18TH, 2022

EDITOR: CHAZEL HAKIM

Nine years ago, I took a gondola up to Harissa, Lebanon, and found myself looking down on Jounieh’s picturesque Mediterranean coastline. Harissa, part of the municipality of Harissa-Daraoun, is located some 18 miles north of Beirut, hovering around 2,000 feet above sea level. My family and I were there to visit the pilgrimage site of the Shrine of Our Lady of Lebanon, and at the top one can see for miles up the coast toward Casino du Liban and south toward Beirut and deep out into the turquoise waters of the Mediterranean. But more importantly, that high and hallowed place can be seen standing—watching with maternal beneficence—over Lebanon and the entire Mediterranean.

Once I made my way over to the pilgrimage site, I remembered my excitement as I looked up at the shrine. The statue was made of 13 tons of bronze. At 26 feet tall, its height was amplified by the 65-foot base it was erected on.

At the time, it might as well have been Mount Everest.

I charged up the stairs, and as I did so I noticed that other visitors of the shrine—several fashionably dressed women—wore Hijabs. Once I reached the top of the shrine, I saw down at the foot of the base a man wearing a taqiyah—a head covering particular to the Druze, an ethno-religious group that practices Druizim (a religion that has origins in Islam)—admiring the statue of Our Lady.

I recall making some comments to my dad about it, but nothing more. Lebanon was

different than America in most ways, so I counted this phenomenon to be a product of a history and culture specific to Lebanon. It was similar to the bullet markings in the condemned buildings scattered throughout the country, standing as a constant reminder of the conflicts and hardship Lebanon has faced.

However, I realized the truth was deeper than this. Religious coexistence in Lebanon has layers of nuances due to the constant waves of war, oppression, and conflict the country continues to endure. That, compounded with the constant onslaught of political corruption and financial mismanagement, only further distracts the international eye from the true message that Lebanon is. The country, because of it’s an economic crisis, has found different means to make reparations for the past injustices, some hidden subtly in Lebanon’s architecture.

The question, however, still remains: how could religious co-existence like the kind I experienced be omnipresent within a country in which wars and regional conflict were predicated on religious motives and disagreement? Analyzing this question through the French philosopher Michael Foucault’s book, Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias, reveals a fascinating observation and provides insight into how religious communities can find peace through spatial play.

While most are familiar with the word Utopia, the origin of the word goes back to the 1500s, when Sir Thomas More, a lawyer, judge, and Catholic saint, collapsed two Greek words together: eu-topia meaning good place, and ou-topia, meaning no place or nowhere.

Now, Foucault coined the term heterotopia to describe certain spaces that are in some way ‘other’: spaces that disturb or disrupt the norm, that are transforming or incompatible, spaces that mirror reality, yet distort its image.

“Something like counter-sites, a kind of effectively enacted utopia in which the real sites—all the other sites that can be found within the culture—are simultaneously represented, contested and inverted,” Foucault described in Of Other Spaces.

A world within a world.

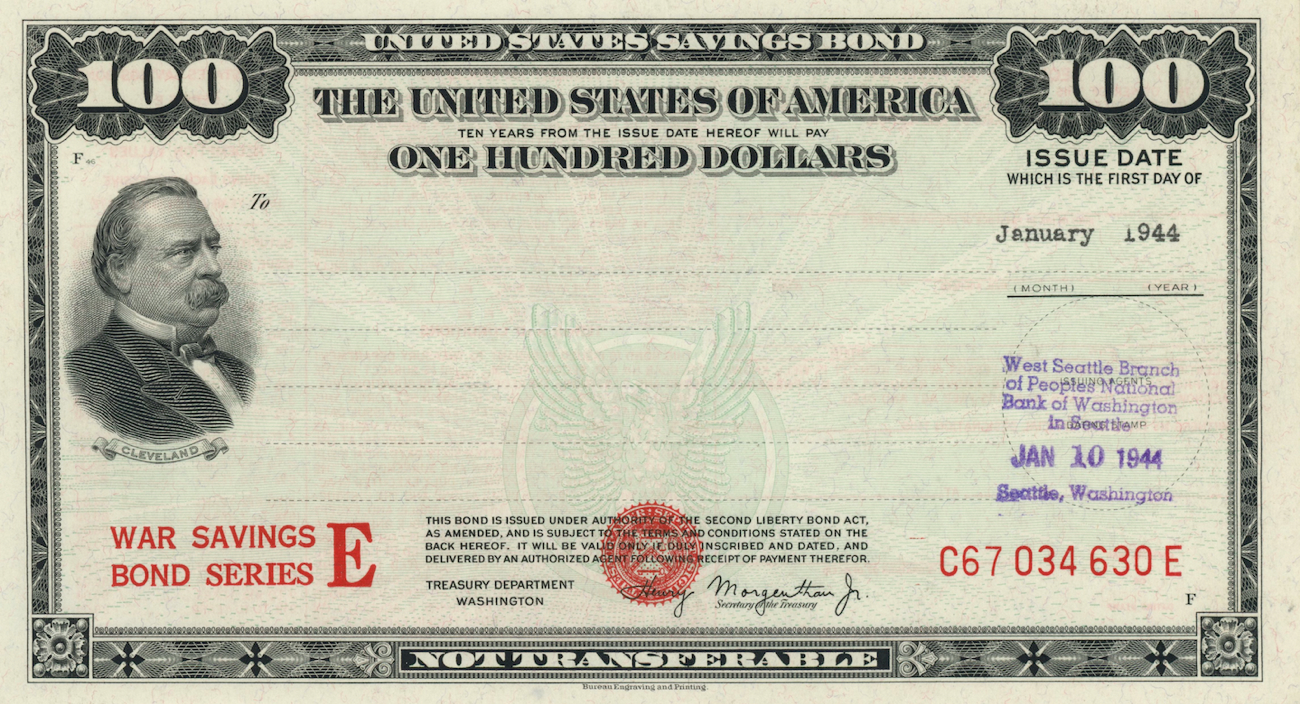

Indeed, heterotopias occur all around the globe by this definition. If a Utopian state of living can never be achieved, then every nation, country, and community that strives for a particular ideology as the “ideal Utopian state of being” leaves behind the attempt to achieve such a state. Examples of this range from the explicit power structure in North Korea and the South African apartheid to the subtle division of residential areas and commercial areas within the US to the stark wealth inequality in the suburbs of Mexico City (Figure 1).

It was authors like Margaret Kohn, professor at the University of Toronto, that expanded on the importance and impact of spatiality, and how it can bring others together or divide them. She observed that “space has implications for how individuals and groups perceive their place in the order of things […] By providing a shared background, spatial forms serve the function of integrating individuals into a shared conception of reality.” In other words, how others decide to move forward in achieving their desired ‘Utopian state’ relies on the organization of land and economic structure, division and topography—puzzle pieces coming together to create the entire picture while each piece has a designated place in order to function properly.

In essence, achieving a utopic state is fully reliant on the socio-economic structure of a given economy. Lebanon’s economy is in one of the worst economic states in the world, with their financial collapse unraveling in 2019, where Lebanese government financial mismanagement and political corruption caused a debt mountain equivalent to 150% of national output. The Lebanese people have long suffered unreliable electricity, rising public debt, financial bankruptcy, and virtually no economic growth for nearly a decade.

On October 17 in 2019, tens of thousands of Lebanese people took to the streets, protesting new tax measures the Lebanese cabinet wanted to enforce, as well as the decades of nationally regulated Ponzi schemes. The protests worked and most of the cabinet resigned. Subsequently, capital inflows also stopped, which forced banks to highly regulate bank withdrawals. Inflation soared. A foreign black market exchange emerged. And of course, the COVID-19 pandemic hit.

Then the Beirut explosion happened on August 04, 2020, and it truly seemed to us that Lebanon, as a country, was done for.

Currently, 70% of Lebanese currently do not have reliable incomes of money and food, and their total collapse of the currency has rendered the Lebanese lira (LBP) (which at the time this article was written was equivalent to 0.00066 USD) highly devalued Currently, the lira is moving further away from it’s pegged rate.

Without a governmental structure in place, no economic infrastructure, and declining educational rates, Lebanon is left vulnerable to outside forces to enter, and in a land where so much sectarian division is still the underlying factor, the landscape is ready and ripe for what Khon refers to as manipulation of space. And the most common result we see as a consequence of manipulating space?

Conflict.

The Middle East is an area of land marked with signs and history of religion, war, and community. The constant power struggle in the area has caused spatial disorientation within many communities, races, and ethnicities through the displacement and destruction of homes and places of worship.

Yet, there appears to be “competitive harmony,” an understanding of what happens if both religions refuse to comply with the common good. Lebanon demonstrates a unique spatial play, particularly regarding religious communities.

While war seems to be a constant, the Lebanese Civil War was one of the most devastating conflicts of the late 20th century and was primarily an internal affair and regional conflict. Outside forces such as Israel, Syria, and the United States also interfered, taking and giving land to benefit their economic needs.

The main conflict of the war, which lasted from 1975 to 1990, was between Christians and Muslims (specifically Maronite Catholics and Sunni Muslims). The power struggle in the government and mounting tension initially set off the war. Once it ended in 1990, there were an estimated 150,000 fatalities and over a million displacements, with thousands of Christians and Muslims accounting for these deaths.

Throughout the first 10 years of the war, the Lebanese economy was remarkably in a steady-state; towards the 1980s, however, the value of the LBP plummeted in wake of the destruction of capital and infrastructure. Lebanon had previously enjoyed its economic status as a regional commercial center, but the depreciation of the LBP did not leave the Lebanese many options to make amends for the sectarian division the war created.

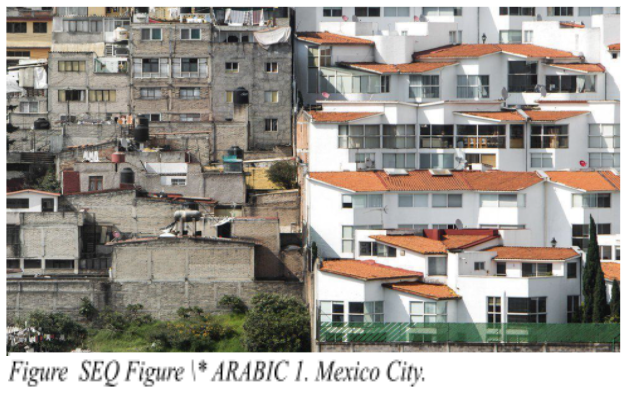

Efforts were made to heal the trauma it brought, and rather than assuming the Western method of ‘coping’, which often includes policy drafts, reparations, and protests (none of which are wrong or incorrect), Lebanon offers insight on how landscape “plays an important role in the constitution of a community by enabling and constraining the way people come together” (Kohn). This is especially seen with the placement of St. George’s Maronite Cathedral and the Mohammad Al-Amin Mosque located in downtown Beirut (Figure 2).

The situation of the Cathedral and the Mosque is a physical representation of competitive harmony, providing us with a real-world example of Foucault’s heterotopia.

When entering a Cathedral, one is expected to genuflect and receive sacraments of purification as an Orthodox or Maronite only. And yet, these two symbolic heterotopias are mere feet apart; the spatial usage is, essentially, shattering the guise of the heterotopia. Rather than each community remaining exclusive to its counterparts, the proximity of both houses of worship suggests the acknowledgment of one another and accepting to a degree what the other means. This results in “competitive harmony,” shared economic ideas while maintaining their own ideologies.

Competitive harmony was especially seen during the revitalization of these houses of worship. During the Lebanese civil war, the cathedral was heavily shelled and hit, plundered and defaced, yet was rehabilitated in 1997. Later in 2016, Paul Matar, the Archbishop of Beirut, installed a new campanile. The campanile’s height was supposed to be 246 ft, following the model of Santa Maria Maggiore Basilica located in Rome, but instead came out as 236 ft.

The reduction in feet was purposeful; the campanile’s stature and the minarets of the Mohammad Al-Amin Mosque stand at an equal height, symbolizing both competition and religious coexistence in a city divided by a sectarian war. The message implied by the placement of the buildings is that of an objective one—spatial stability, a shared, joined reality. The Christians and Muslims must recognize the same reality; if each pursues their own utopian ideals, conflict will result.

Spatial play is reinforced by the placement of the Mohammad Al-Amin Mosque and St. George’s Maronite Cathedral with respect to the Saint George Greek Orthodox Cathedral of the Greek Orthodox Church of Antioch, and it is what makes these two houses of worship some of the most important buildings in Lebanon. About 240 feet north of the cathedral and mosque, the representation that the structures offer as well as their placement indicates coexistence between different religious communities.

Tension between Muslims and Christians will be a constant in Lebanon, and yet because both communities acknowledge the catastrophe that occurs when reality no longer remains objective, through a shared reality they co-exist. Spatiality is the most real concept of the world humans have, and through spatial play, Christians and Muslims have come to live—to the best of their abilities—in peace.

Reflecting back on my experience in Lebanon, I’ve had time to let the memory marinate, and it’s become a bit of a paradox; the layers behind co-existence in Lebanon are very deep and complex, and yet comes naturally, almost intuitively, to the Lebanese. While Lebanon may be an economic disaster, the country represents something fundamental to the human condition: hope.

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.