OLIVIA GINGOLD – APRIL 30TH, 2019

“Everyone is quick to point fingers, but no one has taken the time to consider the role they may play in contributing to the Bay Area’s housing crisis.”

We’ve all heard the stories: “My landlord charges us $1,000 each for a double in a basement that floods when it rains and has black mold.” “My studio apartment with only a common room and a bathroom costs me $2,000 a month.” “My three bedroom duplex costs me $4,000 and I can’t even get the landlord to come and fix the freezer.” It’s almost as if San Francisco Bay Area housing horrors have become a battle to the bottom, jockeying for who has had the worst experience, even as prices continue to soar beyond what seems reasonable. Between the end of 2017 and July of 2018 alone, San Francisco house prices rose by an average of $205,000. This paints a clear picture of what’s been happening in the Bay Area since the clear 2000s; the situation is relatively unique to California, and the Bay Area specifically. The median price of a home in California is more than $500,000, compared to the national average of $250,000.

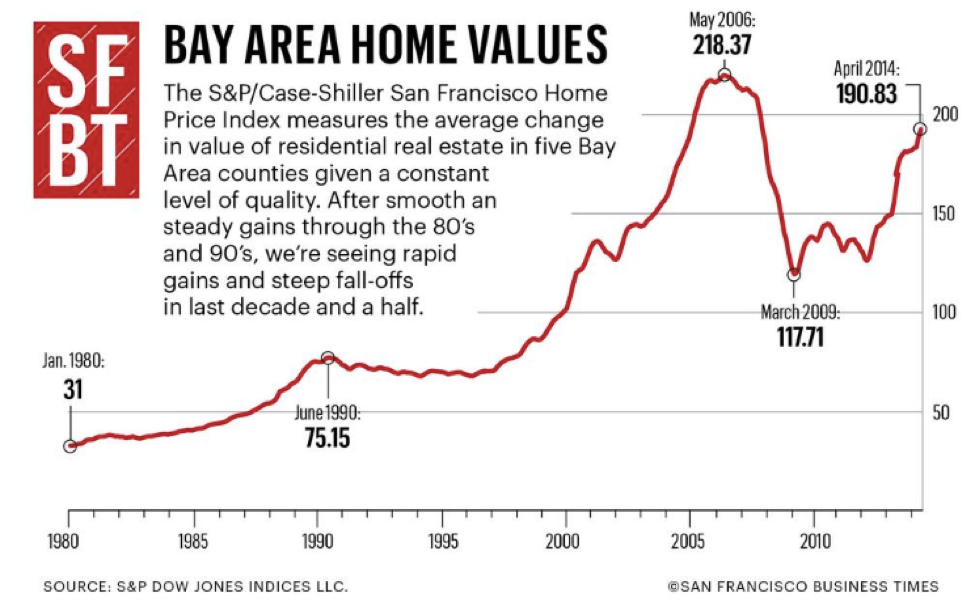

This story can be painted using the simple supply and demand framework. The Silicon Valley is a massive tech hub, drawing from near and far entrepreneurial hopefuls who dream of starting businesses in their garages, and growing them to rival Apple, Google, and Facebook. The influx of people is reminiscent of the Gold Rush era. The Silicon Valley has a booming tech industry, and since 2009, California has added 722,000 jobs, but only 106,000 homes. From 2000 to 2007, Bay Area Cities only accounted for four percent of the state’s population growth, but as the industries in this area grew and flourished, Bay Area population growth began to rise. The proportion of population growth in the Bay Area alone increased from five to twenty percent of new Californians between 2010 to 2017. It is estimated that California currently has a home deficit amounting to 3.5 million, and true to supply and demand, as the demand continues to soar past the supply of housing, prices too will continue to rise. In the figure below, it can be seen that housing prices have risen 200% since 1980.

Source: San Francisco Business Times

But what this supply and demand story doesn’t answer isn’t why demand is rising, but why supply is falling.

California undoubtedly hasn’t built enough housing. 180,000 new housing units a year would be the minimum necessary to keep prices stable; yet, California on average hasn’t met half of that. Many factors have played a role in this lagging residential creation.

Cost of production plays a massive role. Construction is 20 percent more expensive in California cities compared to the rest of the country. This can quickly become a “chicken and egg problem.” Some may muse that as housing prices rose, construction workers had to demand higher wages to afford their homes, while others may quip that construction workers demanding higher wages was what made housing prices rise. In reference to the latter argument, the argument can be made that if housing were less expensive, construction wages wouldn’t be as high.

Proposition 13, which fixes property taxes at the rate they were when a house was initially built or purchased, has stifled a lot of property tax revenue. This has served to decentivize developers from pursuing residential building projects, causing them to focus on retail projects instead. Another deterrent from residential development is that affordable housing is costly and requires subsidies. Coupled with Proposition 13, the likelihood of developers profiting off of these housing projects is low, which also stifles desire to build residential homes.

Even if developers were eager to build residential homes, there’re still significant barriers that face them. A study by George Mason University’s Kip Jackson draws a correlation between California zoning rules and housing growth, determining that California’s regulations effectively reduce the growth rate of new housing, especially in multifamily buildings. In addition to these zoning rules, the disproportionate impact on lower income housing such as affordable housing and apartments is an issue reminiscent of the zoning laws from the Federal Housing Administration during the Great Depression. The zoning laws graded housing areas on scales of red, yellow, and green. Red areas were lower income areas, especially ones occupied by people of color, and it was harder to get housing loans in these areas. This appeals to a problem that extends beyond the scope of just supply. Yes, housing in California is lacking, but what is even more lacking is housing in California that is accessible and affordable to “common folks.” It is these common folks, like teachers, who are ending up homeless and living out of their cars. In addition, while developers wait to get these projects approved, they have to face rabid residents, who complain that new housing (specifically affordable housing) could affect the culture of their neighborhood and contribute to traffic, and pull down the value of their home.

A paradox is at work here though, because the difficulty to build residential housing drives developers to prioritize profitable housing. High-end housing is where the money is, and developers often prioritize luxury homes not only because they’re profitable, but also because neighbors won’t complain that luxury housing is going to pull down the value of their homes. An example of this is in Los Angeles, where only four percent of housing stock has been developed since 2000, and much of it has been luxury homes and condos. Here, when housing is created, it isn’t being created for the people who are more and more pinched by this crisis.

After walking through the process of getting a residential construction project approved, and observing all the obstacles a developer faces for a measly project that won’t even pay off, it becomes more reasonable to wonder why developers would even build any housing at all. The barriers to build housing that exist today paint a very bleak picture. Both formal and informal existing restrictions make it seem like California is trying to limit the supply of housing, rather than expand it. The behavior that is being exhibited here would only be reasonable in times of surplus.

This is not a story of a failed housing market, but rather a story of failed cooperation. Every party involved is quick to point their fingers. Developers point the fingers at cranky residentials. Cranky residentials point the finger at zoning laws. Local governments point the fingers at developers, but developers point the finger back at politicians and proposition 13. If California is going to address this housing crisis, every person, resident, politician, interest group needs to be more open minded and more willing to cooperate and make concessions, instead of pointing fingers. The supply is possible, but not without a group effort. The moral of the story? No one is to blame—and everyone is to blame for California’s housing crisis. If Berkeley students are tired of $8,000 a month four-bedroom homes, and San Mateo residents are angry with overpriced duplexes that lack a backyard, then it’s time to speak up and open our minds, so we can make a conscious effort to cooperate and fix this problem altogether.

Featured Image Source: BioSpace

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.

Why would developers prefer to pay higher property taxes on their completed projects? Prop 13 gives all property owners a tax bill that is consistent and predictable, as opposed to the previous system in which taxes could double, triple or even quadruple in any given year.

Good day very cool website!! Man .. Excellent ..

Superb .. I will bookmark your web site and take the feeds also?

I’m satisfied to seek out numerous useful info here in the put up,

we need develop extra strategies in this regard, thanks for sharing.

. . . . .