RAINA ZHAO – OCTOBER 11TH, 2019 EDITOR: SHAWN SHIN

During every Congress that has convened since 1989, H.R. 40 has been introduced to the House of Representatives, but it has never even been debated on the House floor. Originally sponsored by Representative John Conyers, H.R. 40 is a bill about reparations for descendants of African American slaves. H.R. 40 does not delineate any material policy to implement reparations. Rather, the bill only moves to establish a federal commission investigating the history of slavery and possible remedies. Even so, it has never been successful.

Unlike in years past, however, public support for reparations has increased, and a historic congressional hearing on June 19th of this year to discuss H.R. 40 received significant media and public attention. Now, prominent Congress Members like Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, Cory Booker, and Kamala Harris have all shown support for the bill. As some of the above Congressmembers running for president in the 2020 election, such as Harris and Warren, have also floated possible reparations programs in their platforms, the likelihood of legislative action is greater than ever.

The Legacy of Slavery and Racial Wealth Gap

The need for some measures to address the Black-White wealth gap is clear. Past research on the topic indicates the current state of economic inequality across racial lines is shocking: the Federal Reserve found that the median Black household has ten times less wealth than the median white household. Currently, Black Americans hold less than 2% of the nation’s wealth, despite being 12-13% of the U.S. population.

Several factors have contributed to these disparities, but most, if not all, are traced back to the devastating effects of slavery. When emancipation after the Civil War occurred in 1865, General Sherman famously promised reparations in the form of “40 acres and a mule” for every freed slave, but such a program never came to fruition. Instead, in the century and a half since then, former slaves and their descendants have faced unjust compensation in sharecropping, exclusion from owning property through discriminatory mortgage practices, redlining, and employment discrimination.

Black wealth did accumulate in some areas of the nation, like the Greenwood neighborhood in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Greenwood was predominantly African American, and home to a number of wealthy Black-owned businesses like that of O.W. Gurley, a landowner who sold land exclusively to Black buyers, and J. B. Stratford, a hotelier. Greenwood became increasingly affluent, as the number of Black business-owners, attorneys, and bankers grew, and became known as the “Black Wall Street.” Most of the money in Greenwood was circulated around the neighborhood itself, rather than being spent outside on white businesses. Greenwood’s success soon drew the attention of the white residents living in the surrounding areas. From May 31st to June 1st, 1921, a mob of around 1,500 armed whites, some given weapons by city officials, rioted in the neighborhood. They looted property, burning more than 1,256 homes and leaving more than 8,000 formerly wealthy residents homeless. The Tulsa Riot Race Massacre illustrated how barriers to financial success continued to exist for Black Americans even after accruing wealth.

For many Black descendants of slaves, it has been extraordinarily difficult to amass wealth like their white counterparts. Inequitable economic prospects continue to plague Black Americans even generations after the first emancipated slaves. Low wealth at the onset results in little generational transfer of wealth, with the average Black inheritance being 35% of the value of the average white inheritance. As young Black Americans graduate college, their wealth actually declines on average, as they are more likely than white college graduates to support their parents financially. These factors, among many others, perpetuate the cycle of wealth disparity that started at slavery.

The question now is whether reparations would feasibly and effectively remedy these institutional inequalities, and on whom the onus falls upon to pay for the policy.

What would reparations look like?

Currently, there is no consensus on the details of a reparations plan. Most of the Democratic Presidential candidates, barring Marianne Williamson, do not advocate for direct payments of cash. In fact, Professor William Darity, an economist at Duke University who has been one of the foremost academics advocating for reparations, found that a lump sum payment could actually increase the relative income of non-Black producers as Black Americans gain more purchasing power and consume non-Black goods, leading to an absolute decline in Black income as a whole. Darity has stressed the importance of programs fostering longevity in financial prosperity, such as a public trust fund giving out grants for asset acquisition like homeownership or higher education.

Another suggestion, championed by Democratic presidential candidate Cory Booker, is a baby bond, or savings issued to every infant at birth (Booker proposes a universal bond, not restricted to Black Americans, making his platform less of a purely reparations policy). Such a bond could be liquidated once the child reaches adulthood, when it could be used for college costs or other expensive endeavors.

Considering how racial income inequality is the primary driver of racial wealth inequality, programs like subsidized higher education to encourage higher incomes for Black Americans may have a significant positive impact on the wealth gap. However, others have argued that government benefits locked for specific purposes are overly paternalistic. An increase in the disposable income of Black Americans would allow for better quality of life as it opens access to higher quality everyday goods, such as healthier food and better healthcare. The freedom to spend a lump sum would also arguably afford more personal dignity to descendants of slaves who have already faced excessive institutional injustices.

With reparations programs, however, also comes the question of how to define their recipients. Professor Darity has argued that reparations should only be restricted to the descendants of slaves, a proposal heartily endorsed by grassroots organizations like American Descendants of Slavery. However, information about ancestry is still not universally ready to be tracked. Furthermore, Pan-African activists have objected to the exclusion of other Black Americans. Activist Nkechi Taifa stated to the Washington Post, “It’s extremely difficult to separate classes of black people … the idea that unless you can actually trace your family directly to a slave that you haven’t been subject to the legacy of slavery is a bunch of hogwash.”

The population of Black immigrants to the United States has risen, comprising 8.7% of the Black population. Many Black immigrants come from the Caribbean, which also has a history of slavery. Quantifying reparations recipients will significantly impact how much the government must spend in total to fund such benefits, which brings us to the most ready and vocal argument in opposition to reparations. Who will pay for such an expensive policy?

Costs and Payers

Experts have a wide range of estimates for the exact amount owed to descendants of slaves. Thomas Craemer from the University of Connecticut, for example, placed the total amount at $5.9-14.2 trillion (in 2009 dollars), while Jason Hickel argued that unpaid slave labor from 1619-1865 equaled up to $97 trillion total.

Regardless, with the U.S. federal budget being $4.1 trillion in 2018 ($1.3 trillion of which is discretionary spending), there needs to be a viable way to pay for a robust reparations program. Lawyer Willie E. Gary argued in favor of suing white Southern families who historically benefitted from slavery, while others have suggested a tax on all households in the top 1% of wealth. Unsurprisingly, these proposals are likely to meet with backlash, especially from Americans who have not historically participated in slavery and feel they should not be penalized for a sin they did not commit. Other methods include government bonds to raise revenue, which may phase out the costs of reparations with future returns to the payer.

Despite the punitive aspects of these proposals, however, the American economy as a whole stands to gain from abolishing the racial wealth gap. The racial wealth gap makes for substantial losses in the national GDP as Black Americans consume and invest far less than they would contribute to the economy if they had a larger share of the nation’s wealth. McKinsey reported that the racial wealth gap will cost the US economy between $1 trillion to $1.5 trillion between 2019 and 2028; in other words, closing the racial wealth gap could increase the projected GDP in 2028 by 4-6%.

While the costs and gains of reparations mean that everyone in the United States is a stakeholder, reparations remains a moral issue singularly centered on the experiences of African Americans. The United States cannot reconcile with such an ugly history of racial oppression and brutality without fully addressing it, particularly when such a history still pervades multiple aspects of modern American society. As author Chuck Collins argued to CNN, “People say, ‘slavery was so long ago’ or ‘my family didn’t own slaves.’ But the key thing to understand is that … the legacy of slavery … created uncompensated wealth for … white society as a whole. Immigrants with European heritage directly and indirectly benefited from this system of white supremacy. The past is very much in the present.” With the attention on reparations increasing in both the political and public sphere, the question of recompense for slavery, and more broadly, racial justice as a whole, is here to stay until a satisfactory answer is found.

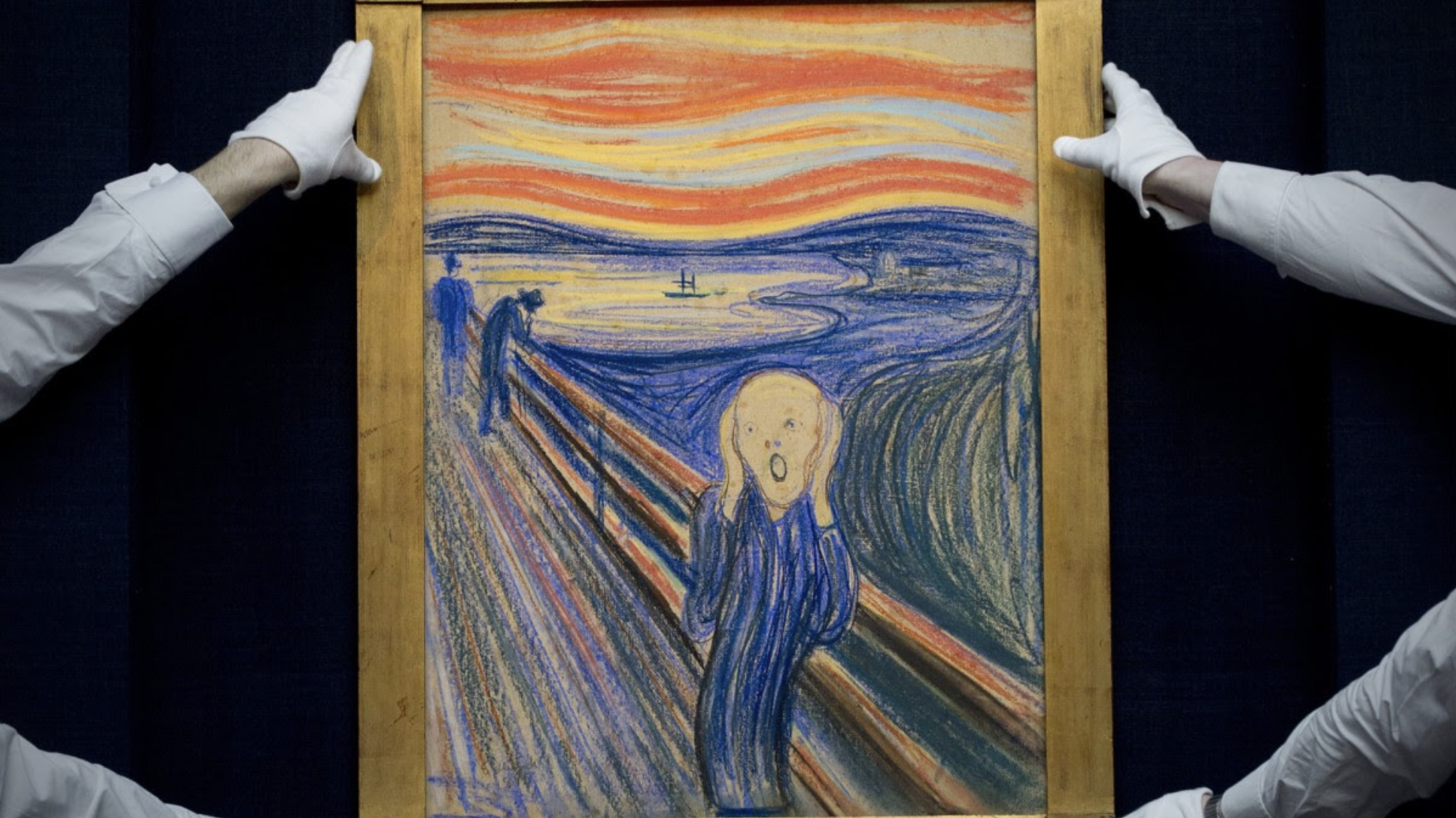

Featured Image Source: The Root

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.

“~~about reparations for descendants of African American slaves.”

insensitive & inaccurate . Our ancestors were enslaved humans . Not SlaVES . REPARATIONS IS repair for 4 centuries of tort

> ADO101.com

American Descendants Of Slavery is the new vibrant movement that has resurrected the Reparations discussion. We are using our votes as leverage and saying #NoBlackAgendaNoVote No longer will Foundational Black Americans do identity politics. We are Agenda-driven . Learn more at ADOS101.COM