HOWARD YAN – NOVEMBER 4TH, 2019 EDITOR: SHAWN SHIN

The Birth of the European Project

Divided and crippled, the great powers of Europe struggled to rebuild after the second World War. Following foreign aid from the US in the form of the Marshall Plan, the countries of Western Europe interwove regional interests to avoid more bloodshed, and after several trade agreements, the European Economic Community (EEC) was born on March 25th, 1957. Under the EEC, economic stability was achieved through common agricultural policy and fixed currency exchange rates. After unstable oil prices weakened currency exchange controls, the European Monetary System was launched. After a decade of success, the countries formally crafted and ratified the Maastricht Treaty, establishing the European Union (EU) and its monetary counterpart, the Eurozone, in January of 1999. While not all EU countries are part of the Eurozone, the latter remains the world’s largest single market. The world watched with interest as an unprecedented project unfolded, and looked on as the poster child of a post-war paradigm took form.

Signing of the Maastricht Treaty | The European Council

The Dawn of a New Era

After the historic cash changeover of 2002, when European countries traded their currencies for the newly minted euro, most believed a new era arose. With one monetary union, previous trade barriers were removed and inspection processes were streamlined, facilitating the flow of goods and services across borders. With one common monetary policy set by the European Central Bank (ECB), prices stabilized and financial markets became more interwoven. As regulations were standardized, business sentiment improved, evidenced by rising cross-border financial flows following the euro’s debut in 1999. Deeper integration gave the euro reputability as a reserve currency, and unified trade interests afforded the Eurozone nations and EU members greater say over global trade policies, notably against the United States. With a collective economic output of $18.7 trillion, a tangible sign of European unity solidified.

A Crisis Hits

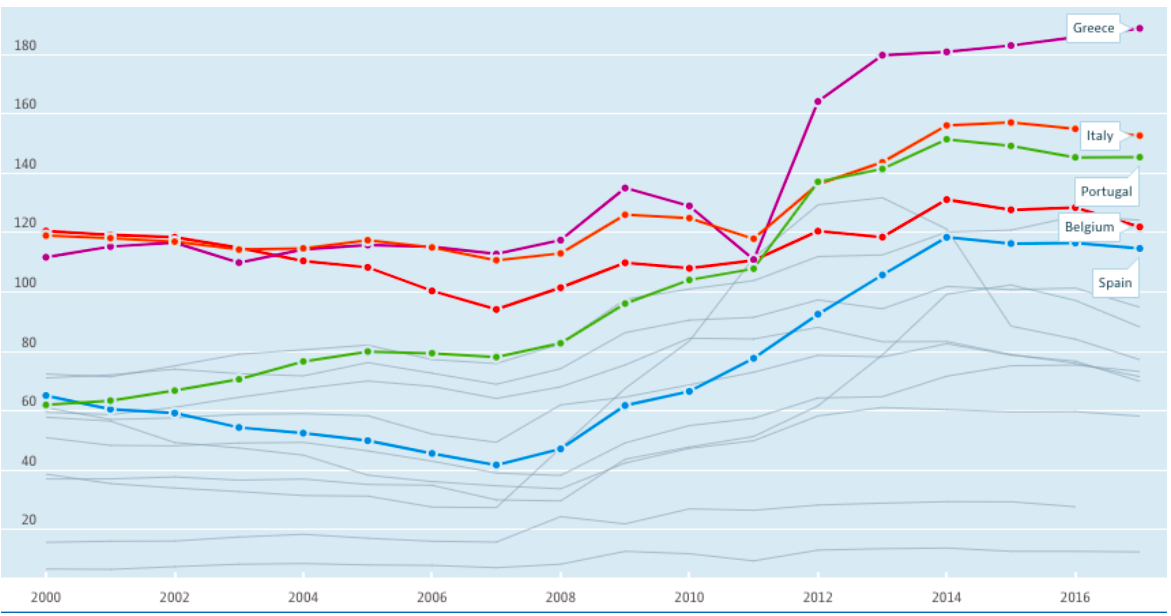

However, the matrimonial bliss following a continent-wide honeymoon was short-lived. The Global Financial Crisis of 2007-2008 magnified the structural weaknesses of the Eurozone project as public spending shot past 5% of GDP, social welfare and education budgets were slashed, and debt as a percentage of GDP soared. The worst afflicted were the Southern European economies: Spain, Italy, Greece and Portugal, who would go on to see debt surpass 100% of GDP and witness double digit unemployment. Interestingly, the only nation to avoid the brunt of the impact was the continent’s financial Goliath, Germany. While Ireland, Spain, and France enacted spending cuts and borrowed heavily, Germany’s borrowing only slightly increased, and output recovered dramatically after two years. This miraculous recovery earned Germany praise for its prudent management, and Southern European countries scorn for their loose policies.

European Debt to GDP Ratios

European Debt | Foundation for Economic Education

Particularly inundated by criticism was Greece, which found itself with the highest Eurozone unemployment at the time. Currently standing at over 20%, the Hellenic Republic has seen several bailouts by the EU and the IMF to the tune of $330 billion, or around 180% of GDP. This crisis had well-laid groundwork before EU membership.

A Precocious Climate

After seven years of military rule from 1967-74, Greece elected a new government which promised to steer the country in the image of the working class. To that end, it spiked government spending, creating a bloated public sector and severe inflationary pressure. To allay concerns, generous welfare payouts under the administration of the Panhellenic Socialist Movement were disseminated, only to produce budget deficits above 3% per year. The party, concerned with bolstering political support, then reduced incentive to work by relaxing retirement ages to 58 for men and below 50 for women. This soon resulted in lower employment and an ever-growing financial burden for young Greeks entering the labor force. The overall sentiment began to dim, and many wondered if Greece would be left to the mercy of international creditors.

Unsurprisingly to speculators, productivity plunged and the government took an even more drastic step by devaluing the Greek drachma in 1983, cutting deeply into household purchasing power. This was a misinformed policy, especially for a country heavily dependent on imports of raw materials. Subsequently, manufacturing slid and the government became desperate for a semblance of normalcy. An increasingly insolvent country was forced to accept outside help and accede to external demands.

Ode to Europe

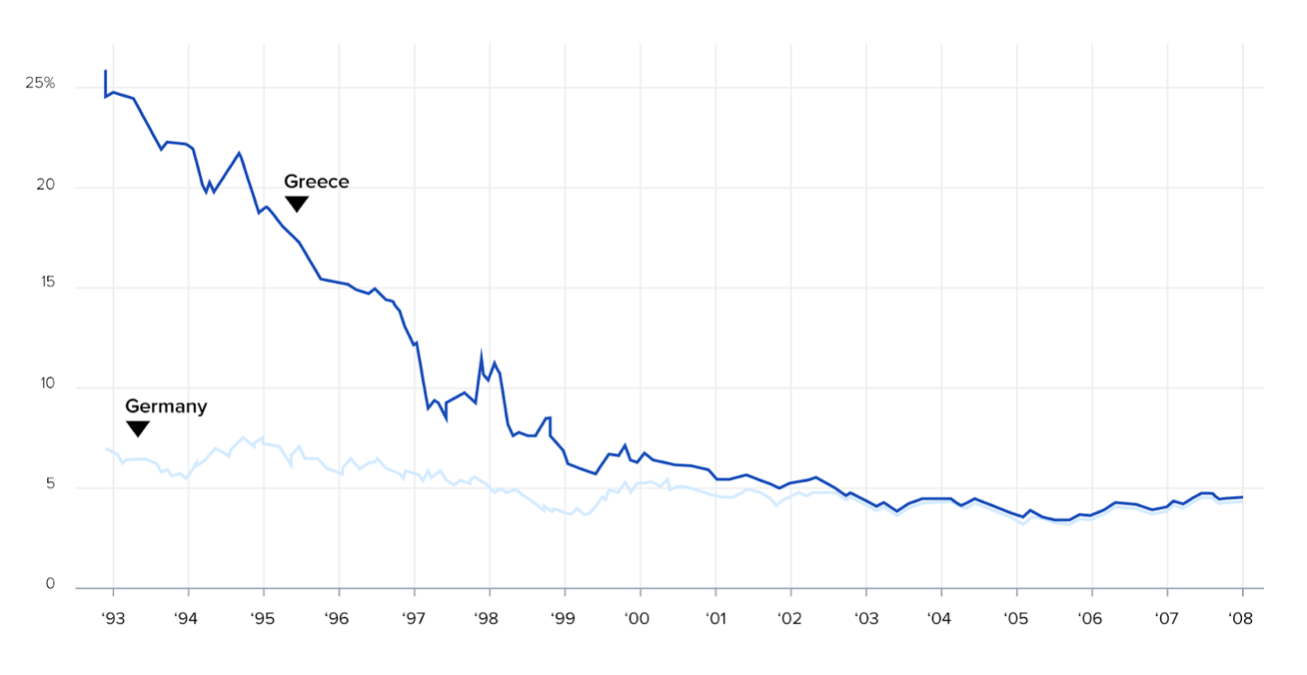

Alarmed by increasingly unsustainable debt, the Greek government resolved to fix its financial woes by making a bid to join the EU. Wary leaders reluctantly accepted Greek membership, and Greece, for its part, implemented budget cuts to remain in line with treaty obligations. Investors regained confidence as the euro presented less volatility. The government, for its part, took advantage of lower interest rates to borrow yet again, producing rapid GDP growth. Unfortunately, the facade soon dissipated and budget deficits widened further to a staggering 12.7% by 2009. Investors subsequently demanded higher returns on government debt, rendering repayment virtually impossible on financial instruments that were downgraded to near-junk status. When it became clear repayment was out of the question, Greece found itself locked out of international markets, forcing it to accept bailout programs from the Troika—the IMF, the European Central Bank, and the European Commission—in exchange for harsh austerity measures. Spending cuts fueled mass protests, and though the measures finally ended in 2018, the country has not fully recovered, and still remains on the brink of recession.

Greek and German Government Bond Rates

Greek Government Bond Rates | The European Commission

After contracting by 25% during the debt crisis, the Greek economy registered a weak 1.9% expansion rate in 2018. That is despite the ECB restarting its quantitative easing (QE) program last month, as interest rates tumbled to -0.5%. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) growth halved in 2018, and wage growth has remained stagnant. While cash restrictions have been lifted and minimum wages have been hiked, firms have struggled to accommodate and comply with higher taxes, which followed after years of failed government policies and resentment from an increasingly distrustful public.

An Ephemeral Comeback

Whether or not the Greek Isles return to solvency is contingent on future policies. Years of mismanagement have fundamentally altered the tax code, and business sentiment remains volatile as global economic trends, including the US-China trade conflict, weigh on overall growth. The Eurozone area’s low inflation and high debt rates have left many economies struggling to foot the bill for an aging population. Combined with yet another Brexit delay, the future of the Union, including that of Greece, is increasingly nebulous. After a new election in 2019 saw a pro-business government elected, one can only observe as the cradle of Western civilization regains its footing. Nevertheless, optimism is not altogether unmerited; Greece is on point to recover its losses by 2033 and remains one of the Eurozone’s fastest growing economies. Only time will tell if the collective efforts of the Greek people overcome ingrained structural deficits and return Greece to the path of steady recovery.

Featured Image Source: Amazon UK

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.