ARDA TUNCTURK – MARCH 6TH, 2024

EDITOR: EVAN FREDERICK DAVIS

Imagine coming home from work. You sit down, grab something to eat and drink, and then turn on the TV. On the screen, you see the same old debate between politicians, normative philosophers, and social scientists: taxes. Should the rich be taxed more? Should the poor be given tax credits to help them survive? Among all of this, you ask a very simple yet profound question: What is the point of arguing over marginal tax rates anyway?

Unless you’re an athlete or very rich, you would arguably be completely right. For many people, the marginal tax rate does not affect their day-to-day lives. While you do have to pay some taxes when purchasing gasoline, many states do not have any taxes for groceries, and, barring economic anomalies such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the income tax rate you face yearly will probably never change. So, with that being said, is wondering about the marginal tax rate completely useless? No.

In economic theory, marginal tax rates are seen as a way of funding public projects and reducing income and wealth inequality, with a new and growing emphasis on the latter. So, rather than just thinking of taxes as the traditional mechanism with which the government amasses revenue that will be used to pay for various social, military, health, and development programs, one could also think of taxes as a way to combat wealth inequality and support the middle and lower classes in a given country. That said, while this article will mainly look into optimum taxes in terms of minimizing wealth inequality, it’s also worth looking at the optimum tax rate in terms of the maximization of government revenue. While minimizing economic inequality is certainly an admirable goal, it would not mean anything if everyone in the country had a low standard of living. In this case, although inequality would be very low since wealth is not unequally concentrated in a certain percentile of the population, since people have a low standard of living, this minimization of inequality is not really doing any good for the general welfare of the people. This is where looking at the maximization of government revenue comes in.

If one were to maximize government revenue, then the government could create more social programs, build more infrastructure, and provide more stimulus than it would under a non-optimum state. While we would not be minimizing economic inequality under this model, we would be increasing the standard of living in the country, which is another incredibly important goal and further highlights how important taxes are as a mechanism that the government can use to improve all facets of the economy.

Economic Growth, Productivity, and International Mobility

Two of the main talking points surrounding tax rates are the effect of increasing taxes on economic growth and productivity. Alinaghi and Reed (2020) find that a 10% increase in taxes in some cases produced a 0.2% decrease in GDP, and in other cases produced a 0.2% increase in GDP. That is to say that even a significant increase in the tax rates has only a moderate impact on a country’s GDP. In contrast, a paper by Romer and Romer (2010) found that the robust effect of a 1% increase in taxes corresponds to a roughly 2.5% decrease in a country’s GDP. An explanation for the differences in the findings between these two papers is that Alinaghi and Reed fail to account for the type of tax rate increases that are implemented. For example, a higher marginal tax rate (a progressive tax) on top innovators in the United States — who also, for the most part, make up the richest citizens in the United States — could decrease innovation within the United States, which in turn would cause a decrease in GDP.

This idea is exactly what Akcigit & Stantcheva (2018) found in their paper when analyzing the effects of U.S. state marginal tax rates on patent production. They noted that an increase in the marginal tax rate decreased patent production. Furthermore, Stantcheva (2020) further corroborated the idea that an increase in marginal tax rates for top earners could reduce innovation since the top earners are also the top innovators.

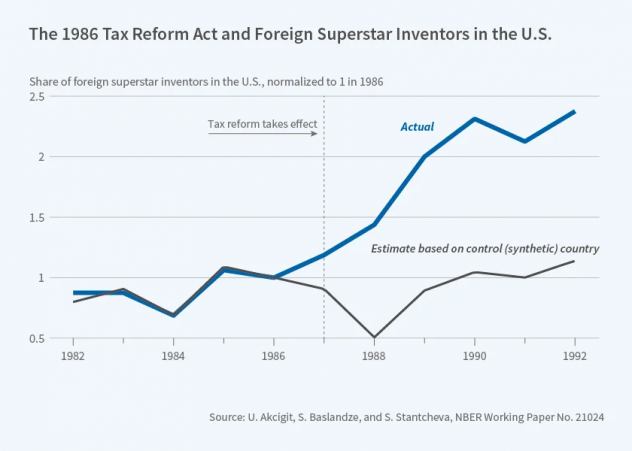

Along those lines, Akcigit & Stantcheva (2018) also analyzed the effects of an increase in taxes on international mobility — how investors choose to migrate to different countries based on each country’s given tax level. They analyzed the U.S. 1986 Tax Reform Act under the Reagan administration — which lowered the top tax rate on ordinary income from 50% to 28% — finding that the number of top 1% foreign investors in the U.S. increased after the act passed into law relative to a synthetic counterfactual country. A synthetic counterfactual country is a country that had the same trend in the number of foreign superstars as the U.S before the new tax code implementation in the U.S. This synthetic country is used as a control group in the experiment to see what would have happened to the number of foreign superstars in the U.S. if the tax change was not implemented. The difference between the synthetic country and the U.S. after the implementation is the treatment effect caused by the new law. These findings suggest that it may be beneficial to a country’s economy to decrease taxes if its goal is to increase innovation and economic growth. In terms of policy implications, if the U.S. were recovering from a recent recession, then decreasing taxes — on top of the regular monetary policy response — could lead to a quick recovery, as lower taxes would cause growth and productivity to increase, which would increase GDP.

Photo Credit: Akcigit & Stantcheva (2018)

Taxes and Public Policy

Now that the effects of increasing the taxes have been talked about, what is even the point of increasing taxes in the first place? Over time, there has been a shift in economic discourse regarding social welfare. For many years, economists focused on income inequality as the driving force of evaluating how unequal a country’s economy is, and it, understandably, was a pretty good measure. Financial assets, such as stocks, were far from being the main makeup of a person’s wealth. However, throughout the last decade or so, wealth concentrated in the top 10% has grown a lot faster than income concentrated in the top 10% in the United States, according to the Realtime Inequality database by Thomas Blanchet, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman. This growing wealth inequality inside the United States has led to discussions about progressive policy measures, such as progressive wealth taxes, which are tax rates that increase as one’s wealth increases, with the tax rate depending on the wealth bucket that the economic agent is in.

Even if there is significant discourse about using wealth taxes to curb inequality between America’s rich, the middle class, and the poor, many economists have tried to utilize mathematical economic models to determine the “optimal” tax rate, where the optimal tax rate is defined as the one that maximizes the social welfare of society. This is typically measured in terms of monetary consumer and producer surplus, where consumer surplus is the benefit received by consumers for paying less for a good than what they value it, and producer surplus is profits for firms. This is referred to as the Utilitarian perspective on social welfare and is, for the most part, the most popular way of measuring it. There are also the Libertarian and Rawlsian perspectives. Libertarians reject the concept of measurable utility and instead focus on establishing a regulatory framework promoting free entrepreneurship, and Rawlsians conceive of social wellbeing as the utility of the person who is the worst off in society. Some possible reasons for why these two perspectives are not used in economics are that the Libertarian perspective does not allow for the consideration of public policy in the form of wealth transfers since it does not consider utility to be measurable, and the Rawlsian perspective focuses too much on the poorest individual’s situation at the expense of society as a whole.

With that being said, Piketty, Saez, and Stantcheva (2014) found a highest marginal tax rate of 83% for top labor incomes. Granted, there might be issues, such as international mobility effects or tax loopholes exploited by the rich, that change the marginal tax rate for behavioral reasons. Nevertheless, this is a significant finding and contributes to the idea that higher marginal tax rates on the top income brackets are in fact a way of reducing income inequality, which is in itself a significant societal and economic goal for any developed country. In addition, while the paper looked at marginal tax rates in the form of optimizing the level of income inequality rather than maximizing societal welfare, in a country like the U.S., which is already pretty rich across the board, the goal should be to minimize inequality between the rich and the poor rather than trying to increase what is already probably a high level of societal welfare.

Interestingly, when Piketty and Saez (2013) analyzed optimal inheritance taxes (an example of a wealth tax), they found an economically conflicting idea: people in the highest bequest percentiles should receive inheritance subsidies, whereas people in the lowest bequest percentiles should face an average inheritance tax of roughly 50% in the United States and a little more than 55% in France. Additionally, the paper also notes two studies — Chamley (1986) and Judd (1985) — that suggest that in an economy with zero stochastic shocks (i.e., random economic events), the optimal inheritance tax is 0% in the long run, since any nonzero tax would distort intertemporal economic choices by economic agents, which would in turn harm economic decision making due to complications in the short term decision-making process.

To note, there is dissent from libertarian-leaning economic think tanks, such as the Cato Institute, who argue that the traditional derived optimal tax formulae produce too generous marginal tax rates (sometimes as high as 83%) due to flawed economic assumptions in producing said mathematical models. They also argue that there is a general lack of empirical substantiation for optimal tax claims, on top of incorrect assumptions that higher marginal tax rates on the top labor income brackets do not affect future taxable capital gains, corporate gains, and GDP.

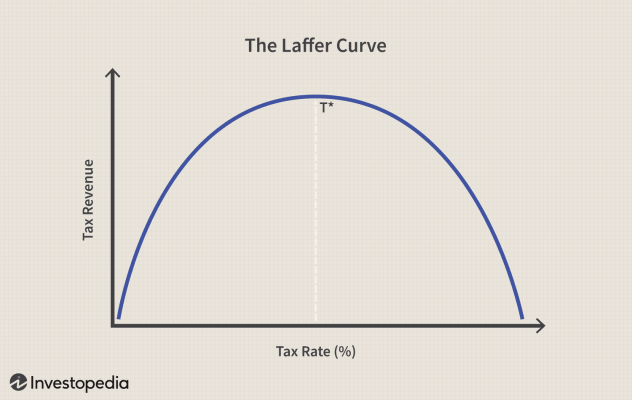

The increasing concentration of individuals’ wealth — mainly in the form of financial assets, such as stocks — has led to a discussion about an optimal capital gains tax structure that minimizes wealth inequality. While research on this topic is sparse, a Joint Economic Committee study by the U.S. Congress, authored by James D. Gwartney and Randall G. Holcombe, does discuss an optimal (in terms of government revenue) marginal capital gains tax of 20%. While the paper does not analyze the optimum rate for wealth inequality, it does provide some estimate as to what optimum capital gains taxes could look like. Something interesting to note is that the suggested capital gains tax of 20% was actually lower than the tax rate at the time (1997) of 28%, which is consistent with the idea that a tax rate that is too high can decrease innovation and economic growth, which would decrease overall wealth taxable in the future. Thus, a higher tax rate does not necessarily suggest higher government tax revenues. This idea of an optimum tax rate in terms of government revenue maximization shows up in economics in the form of the Laffer curve, which is a curve where government revenue originally increases but later decreases as a function of the tax rate. Therefore, the optimum rate of tax is one that is neither too high nor too low based on the given curve. While the curve is critiqued as “too simple” by some economists, it is nevertheless a good illustration of how a tax rate that is too high disincentivizes innovators, which in turn decreases total taxable wealth.

Photo Credit: Investopedia

With taxes being seen as a “necessary evil” by many people, it can be difficult to remember the profound effects that taxes have on the economy as the whole. To think that taxes exist in an isolated echo chamber where they only affect government revenues would be sorely wrong. Taxes affect economic growth, innovation, and have significant effects on public policy in combating income and wealth inequality, along with bettering the standard of living in a given country. So, while it may be boring for some, it is a “necessary evil” for those bored by the effect of taxes to read up on all of the different outcomes caused by a change in the marginal tax rate, whether it be an inheritance tax, income tax, or something completely different.

Featured Image Source: Patriot Software

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.