SANIYA PENDHARKAR – NOVEMBER 20TH, 2023

EDITOR: SELINA YANG

Football. Fútbol. Calcio. Soccer. Whatever it’s called, the “beautiful game” is played by children in practically each country. Every four years, nations hope to make a permanent mark at the FIFA World Cup and return home as champions of the world. However, as countries train intensely to give their best performances at the tournament, those who host the cup work endlessly to deliver the grandeur.

With millions of live fans and a television audience of over one billion, hosting the world cup is a wildly expensive endeavor for any country. But, hosts hope that the expenses will serve as an investment into the country’s future. For 28 days, the attention of the whole world is on a single nation via tourism, broadcasting rights, and ticket sales.

However, hosting does not always reap the glamor it predicts. As Qatar and Brazil proved in the 2022 and 2014 world cups respectively, there is a dark side to the economics of being a host nation. This article will explore how financing a multi-billion dollar operation is not a straight path., The social costs of managing the world cup should not be ignored.

Qatar- How Did the Government Finance the Endeavor?

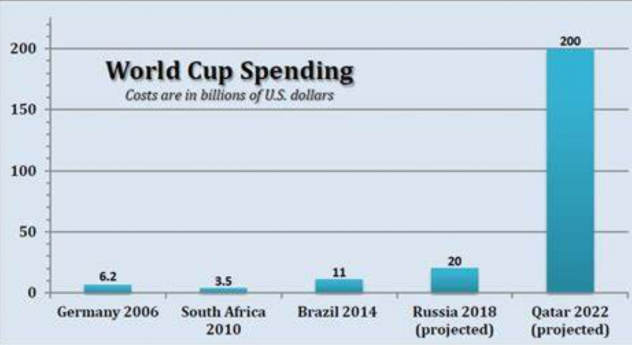

The 2022 World Cup hosted in Qatar was by far the grandest world cup to date. With an average of 11.6 million viewers per match, it’s not surprising that Qatar’s 2022 campaign generated approximately $7.5 billion dollars in revenue — the most revenue of any FIFA World Cup. The Qatari world cup broke a number of records in a number of categories. However, most notably, it easily became the most expensive world cup. With an estimate of roughly $220 billion dollars, the 2022 world cup was about 16 times more expensive than the previous world cup in Russia.

Image source: Bloomberg

Image source: Bloomberg

How did such a small developing country with little to no football acclaim finance such an endeavor? In this section, I will explore the hidden social and financial repercussions Qatar experienced as a result.

The initial proposed stadium costs of $4 billion for the Qatar world cup quickly increased to between $6 billion and $10 billion dollars. Until this point, the average stadium cost was between $1.5 and $3.5 billion dollars. The infrastructure package, which included the proposed stadium costs, cost about $220 billion dollars. While the package did consider Qatar’s future plans of becoming a booming technological and innovation powerhouse, the new hotels, transportation, and airport operations cost directly influenced its hosting of the world cup and is therefore counted towards total costs. Additionally, the predicted 1.2 million visiting fans (half of the country’s population) mandated a renovation of the sewage system since the current system was only adequate for the existing population: a very expensive process to say the least. So, where did all this money come from?

Despite its small geographic size and overall low international profile, Qatar is the sixth richest country in the world. With a GDP per capita predicted by the International Monetary Fund of $81,968 USD, it ranks higher than the US on the board. Qatar was not always rich, in fact, it has accumulated its immense wealth rapidly over 50 years following World War II. This is thanks to one invaluable resource: oil.

While it’s hard to measure the exact amount of oil in the country, its reserves are estimated to be roughly 25 billion barrels. This plethora of oil is highly sought after and has garnered foreign investment into the country, contributing to its wealth. From oil and natural gas profit alone, Qatar has a Sovereign Wealth Fund of $170 billion dollars. The government invests this money further into hedge-fund like operations in order to amass more wealth. Qatar’s interests were further catered to during the geopolitical unrest of the Russia-Ukraine War. With nations looking to shift away from Russian oil Qatar became a point of interest for many, and while Qatar did not have the ability to replace Russian oil, it certainly helped to diversify the supply to nations. Within this increase, export sales of fuels and oil grew by almost 30% partly attributed to the Russia-Ukraine War. In 2022, Qatar exported about $109 billion dollars worth of goods — a 24.6% increase from 2021.

Even with government spending financed primarily by oil money, Qatar citizens saw a steep increase in taxes to help appease the infrastructure costs. But is tax profit from such a small nation with no personal income, inheritance, social security, nor property tax substantial enough to finance a large project? Qatar implements a 10% investment and capital gains tax rate for non-citizens. Corporations owned by Qatar and most other Middle Eastern countries are exempt from corporate tax, but foreign owned companies experience a rate of 10%. What is truly eye catching however, is the whopping 35% corporate tax foreign oil and gas companies must pay further proving that oil is the forefront of profit in Qatar.

While Qatar certainly made a name for itself with its vibrant cities and rich atmosphere during the world cup, it faced a great deal of bad publicity leading to a poor image amongst foreigners. Qatar was accused of human rights violations in the construction of the stadiums. Domestic and migrant workers were reported to be experiencing illegal recruitment fees, salary theft, injuries, and even unexplained deaths. Furthermore, systemic discrimination regarding women and other minorities tainted Qatar’s image.

Thought to be on the other side of the same coin, Brazil’s world cup experience also highlights the economic strain the world cup brings.

Brazilian Nightmare – The Darkside of Hosting

The 2014 Brazil World Cup, like Qatar, was the most expensive world cup to its date. With unlimited talent and a beloved football team, they were even favorites to win the tournament. However, their devastating loss to Germany in the Quarter Finals was not the only nightmare that Brazil experienced — the economic consequences of hosting the lucrative tournament was simply too much for the nation to bear.

In order to spread the wealth of the World Cup, Brazil decided to have 12 host cities instead of the required 8. However, the country spread itself too thin as more cities meant more stadiums, hotels, and infrastructure which was too large a strain to handle. When Brazil was announced to host in 2007, inflation in the country was about 3.6% . In 2008 however, the financial crisis skyrocketed inflation as the government continued its spending. So, by 2014, citizens were angered by the implemented tax increases to finance the World Cup.

Many hoped that hosting the tournament would help lift Brazil from its economic slowdown. At the time, Brazil ranked in the top 10 largest economies with a GDP between $2.2-$2.4 trillion dollars. However, in that year, the economy measured a growth rate of just 0.1%. In the previous four years, the economy slowed down for a number of reasons including low investor confidence, low commodity prices, and a lethargic global economy. Additionally, Brazil’s Gini Coefficient tells a revealing story. The Gini coefficient is a value between 0 and 1 which measures the level of inequality in a country, where 0 is perfect equality and 1 is perfect inequality. Brazil harbors a coefficient of 0.547 indicating substantial wealth inequality in the nation and placing it 13th highest amongst countries with available data.

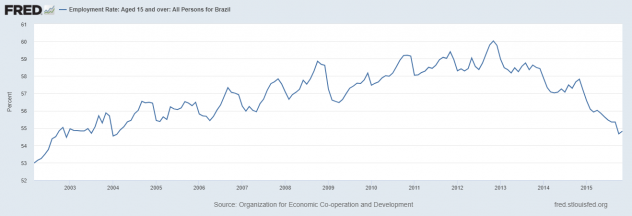

Despite the $14 billion dollars the World Cup put into the Brazilian economy, the total costs themselves were over $11 billion dollars,with $3.6 billion dollars coming from taxes. During the tournament, Brazil experienced employment struggles. The high unemployment due to the slowdown of the economy was hoped to be offset by the predictions of one million new jobs. However, the greater employment did not prove too influential for the economy. During game days, many businesses declared holidays and even if they didn’t, the majority of workers picked football over their jobs. So despite the enormous number of potential jobs, Brazil’s employment rate actually decreased.

Image source: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

Figure shows the employment rate of people aged >15. During the 2014 World Cup (June-July) the graph shows low employment rates.

The nation gravely overestimated the long term benefits of being hosts. The almost 4 million tourists were estimated to generate around $3 million dollars for the Brazilian economy. However, even after ticket, transportation, and living expenses, tourist revenue accounted for only 2.5% of the $14 billion dollar cost. Additionally, one of the greatest long term effects is the use of infrastructure that was created for the tournament. Stadiums created to seat almost 50,000 spectators were allotted to fourth division football teams who just barely average 1500 spectators. The revenue generated is not sufficient to maintain the stadiums signifying a net loss over all. In the years leading to the tournament, the government promised to construct the much needed infrastructure, which caused excitement in the developing nation. However, as the world cup neared, projects were dropped in favor of tournament related endeavors with many of them still remaining unfinished. While Brazil now has glamorous airports, its own citizens can never benefit from them as they are still waiting on the basic renovations to roads and plumbing that was promised.

The figure shows that rather than the Brazilian economy booming after hosting the tournament (as predicted), Brazil experienced a harmful two year recession with the economy contracting by roughly 7%. Image source: What’s gone wrong with Brazil’s economy? – BBC News

Arguably greater than the economic impact, the social impact in Brazil was detrimental. In preparation of construction for the tournament’s facilities, almost 200,000 residents were evicted and many relocated to

scrappy huts without adequate water or electricity. To put into perspective, the $11 billion dollars that went into financing the world cup is equivalent to the cost of providing social welfare to about 50 million Brazilians who would have greatly benefited from it. This displacement caused increased child labor, violence, and social unrest leading to a greater increase in the equality gap between high and low income families.

Concluding Remarks

Brazil’s economy never truly recovered from these tournaments and the Covid-19 pandemic only made it worse. There are a number of similarities between them. Both have rapidly growing economies and similar higher-end Gini coefficients, continue to be classified as developing countries, and have hosted incredibly expensive tournaments. However, unlike Brazil, Qatar does not raise any excitement in the footballing world outside of their world cup feature. Therefore, it’s likely they will face a worse issue than Brazil in stadium profitability. Qatar recently publicized their interest in the bidding for the 2036 Olympics implying that they plan to grow their reputation in the global economy. However, Brazil hosted the 2016 Olympics which only exacerbated the negative effects of the world cup. But, while Qatar seems to be following Brazil’s footsteps, it is too soon to say anything for sure.

Featured Image Source: Bob’s Watches

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.