AAYUSH SINGH – MARCH 15 2022

EDITOR – MILLIE KHOSLA

When the world came to a screeching halt in March of 2020 because of the coronavirus pandemic, economic policy seemingly underwent a seismic shift. The CARES Act, signed into law by President Trump, provided $2.2 trillion of stimulus to an economy in the midst of an unprecedented crisis, which included everything from direct cash payments to forgivable loans. The Federal Reserve took swift action as well, engaging in a trillion-dollar bond-buying campaign to provide liquidity to American markets in an effort to shore up corporate balance sheets. These measures – coupled with President Biden’s American Rescue Plan – prevented much suffering in an unprecedented time. In the early months of the pandemic, the generous relief package actually caused a reduction in poverty.

As a result, unemployment currently sits at 4% and the economy grew by 6.9% in 2021, the fastest in decades. However, the robust recovery has sparked its own set of concerns, revolving primarily around inflation: the increase in prices for goods and services. The Consumer Price Index rose by a staggering 7.5% last year, leading to questions about whether the government had done too much in response to the COVID-induced recession. The spread of the Omicron variant and continued uncertainty about the pandemic mean that much will remain unanswered for the foreseeable future.

Against this muddled backdrop, then, it would be worthy to look back to understand what lessons we can glean from history to move out of this crisis. The last time this country saw a major outcry about inflation and economic growth was nearly a half-century ago, during the stagflation crisis of the 1970s. The economy during this period illustrates a great deal about public policy, economic theory, and the politics of inequality that are relevant to the economic crisis today.

What Happened in the 1970s?

Perhaps the most famous cause of the 1970s-era malaise is oil. As the historian Jonathan Levy recounts in his book Ages of American Capitalism, OPEC imposed an embargo against the United States in response to the Yom Kippur War in 1973. The move precipitated a 400% increase in the commodity’s price; in a nation where the auto industry was crucial to the economy, an explosion in the price of a critical input had severe consequences for the nation’s economic health. Needless to say, President Carter captured the general feeling of the country well when he famously said the United States was suffering from a “crisis of confidence.”

This crisis of supply serves as useful context for today’s economic challenge. One driver of current inflation is the practice of just-in-time manufacturing, whereby companies order and receive inputs only when they’re required. As one can imagine, the pandemic threw a wrench into this system. The best example of this is the auto industry: because of shortages in computer chips that vehicles rely on, the price of used cars grew exponentially.

Interestingly, the extent to which the situation today resembles the 1970s has become an indicator of one’s political beliefs. Proponents of the view that inflation is transitory point to these COVID-induced supply shortages to argue that the government should not act with a heavy hand in tamping down inflation. More moderate and conservative economists disagree, however, attributing inflation to the Biden Administration’s spending. Instead of looking to the 1970s’ supply shortage as a guide, these academics pinpoint excessive demand as the central issue. Harvard Professor Jason Furman, who served as chair of President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisors, puts forth a version of this perspective; he recently stated that the American Recovery Plan – President Biden’s 1.9 trillion dollar stimulus package – was too much money being spent in far too short a period of time.

Recent data seems to support their view. The idea that inflation would ease as markets restored supply chains has not come to fruition. In the last few weeks, the Fed, which has been wary of raising rates and largely committed to the idea that inflation was transitory, seems to have changed its tune. But a narrow-minded commitment to ending inflation at all costs would be a grave mistake and carry significant economic consequences.

Paul Volcker and His Discontents

In 1979, inflation was still raging until it was upended by one of the most contentious decisions in recent memory, the Volcker Shock. The chairman of the Federal Reserve, Paul Volcker instituted a much tighter monetary policy targeting the supply of money. As a result, two years later, interest rates neared 20%. The move did tame inflation, but in doing so, Volcker had caused a recession that sent unemployment skyrocketing over 10%. The end of stagflation was a kind of Rorschach test: was the cure to the crisis of the 1970s worse than the disease?

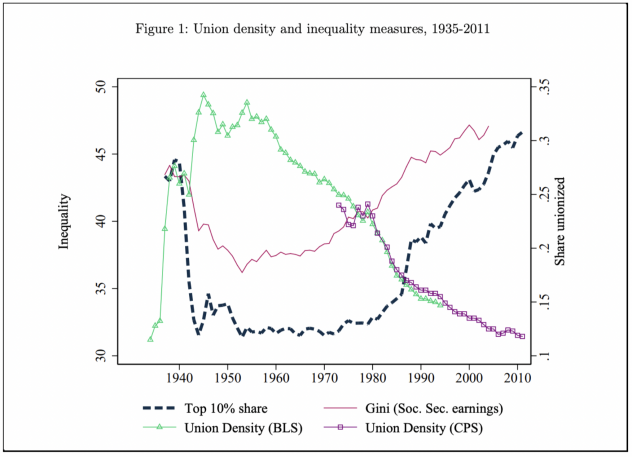

In many ways, the answer is yes: union membership fell 10% in the fifteen years after the Volcker Shock. Today, the number sits at 10.3%. This free fall is especially significant because of its lasting effects: Farber, Herbst, Kuziemko and Naidu show that as union density has dropped, inequality has rapidly risen. In 2021, the richest 1% of Americans owned 70% of all U.S. wealth.

This inequality took on an international flavor, too. In 1982, Mexico suffered a debt crisis as a direct result of the Volcker Shock: because interest rates increased dramatically, the country was not able to pay back its debt obligations. The United States offered a rescheduling program, but in return, forced Mexico to structurally reshape its economy – notably, with cuts to welfare spending. The American government had forced its own free-market vision onto the Mexican economy while intruding on national sovereignty.

A singular focus on inflation today would thus risk repeating the mistakes of the 1970s. In a time of immense inequality, the government restraining the economy could erode worker power even further. In addition, the argument put forth by a number of Republican politicians – that the government should cut spending and adopt an austere course of action – lacks substantive basis. In a paper for the Center for Equitable Growth, researcher Andrew Elrod pinpoints austerity – the reduction of government spending – as a key driver of stagflation (so named because low growth accompanied high inflation). Elrod recounts how the Nixon, Ford, and Carter administrations’ curtailment of public spending only exacerbated unemployment while doing little to curb inflation.

As such, the reaction to inflation is a phenomenon that some observers are increasingly viewing in class-conscious terms. Harvard historian Tim Barker shows that the black unemployment rate rose to 21.2% by 1983, and 90% of job losses were in the manufacturing, mining, and construction sectors. With economy calamity came social dislocation: “in the area around Pittsburgh,” Barker writes, “suicide rates and alcoholism soared.” The policy response to the stagflation crisis was a turning point in American history: the gains workers made during the New Deal order were erased after 1979. This illustrates an important point for today: at a time when workers already have such little power compared to the 1970s, a Volcker-esque response would be severely harmful.

Big Picture Takeaways

The stagflation era brought about significant big-picture changes in American political economy as well. One paradigm shift was the ushering in of the neoliberal era; a fraught term with many different uses, neoliberalism at its core is a belief in free markets and free trade, exemplified by the deregulation during Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan’s leadership. So what’s the connection with the crisis of the 1970s? For one, a significant part of stagflation had to do with supply; the dominant ideology of the time, Keynesianism, was focused particularly on aggregate demand. And with John Maynard Keynes long gone, economists and policymakers didn’t see much utility in a Keynesian framework. Milton Friedman stepped into the vacuum. Friedman, who had predicted stagflation in the 1970s, was a staunch opponent of government intervention, and his ideas were now in vogue.

Another pendulum swing was a turn towards financialization in the economy around the late 1960s and early 1970s. In her 2011 book Capitalizing on Crisis, Greta Krippner argues, “the state’s ad hoc responses to crisis conditions have reinforced the broader turn to finance in the US economy over the past several decades.” This pivot to finance has brought significant consequences for the rest of the economy. Coupled with the neoliberal prescription to deregulate markets, the rise of finance capital was a contributing factor to the Great Recession. As Berkeley Professor Neil Fligstein outlines in his new book The Banks Did It, a dogmatic faith in free markets on the part of regulators and policy makers enabled the financial industry to engage in the kind of risky activity that caused the American economy to collapse in 2008 and inequality to widen.

That history brings us back to today, and the results of the economic policy response to COVID-19. Though inflation has dominated most of the headlines, the effects that generous government spending had on people should not be forgotten, as Berkeley’s own Blanchet, Saez, and Zucman show. As such, where the crisis of the 1970s was defined by the entrenchment of neoliberalism, a significant opportunity awaits to change the status quo in favor of the historically marginalized. The enactment of restrictive economic policy, however, would squander that opportunity.

The common refrain many give when asked about the importance of history is that it helps us avoid repeating the mistakes of the past. If history is any guide here, it should be clear that a responsible economic policy is not one that focuses solely on price increases, but one that views inflation in concert with inequality and wages. As the 1970s show, a single policy choice by the government can reverberate through the ages. Inflationary pressures are a concern, but massive interest rate hikes or cuts to the social safety net would illustrate one thing: we have still not learned the lessons from the crisis of the 1970s.

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.