TUCKER GAUSS – APRIL 11TH, 2024

EDITOR: BECCA PENG

Sometimes you wonder if economists ever step outside their lecture halls. Monopolies aren’t businesses, they’re a series of curves on a graph. Consumers aren’t people, they’re utility functions.

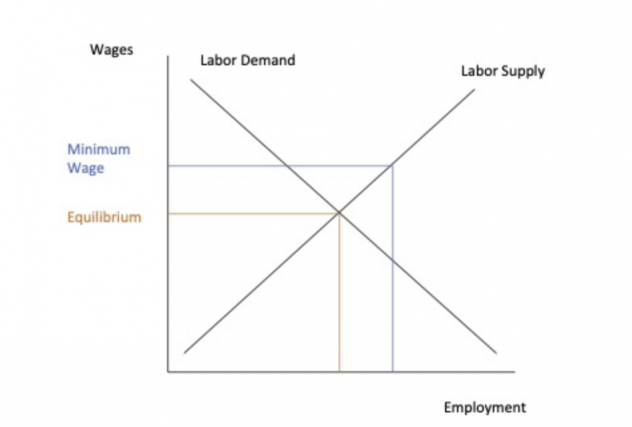

Not only do these models oversimplify and dehumanize, but they generally fail to hold up in real life. Look no further than David Card’s famous minimum wage paper, which illustrated that raising minimum wages actually increases employment in some sectors. This completely contradicted the theoretical status quo that raising wages should reduce employment.

Image source: Study.com

Image source: Study.com

The empirical application of economic theory to real markets is now almost ubiquitous among researchers. In this tradition, I interviewed Vanessa Vichit-Vadakan, a worker-owner at Cheese Board—everyone’s favorite Berkeley pizza place—to learn more about the real-world applications of labor models.

So…What CAN Cheese Board Tell Us About Labor Markets?

To no one’s surprise, inequality is one of the biggest challenges of the current US economy. Incomes are stagnating, and costs are rising, particularly among the middle class. Marx might’ve been right after all: in the current market, it seems that owners exploit workers for their value.

To combat this inequality, some economists promote cooperative worker businesses, or coops. At Berkeley, Cheese Board is well-renowned for its coop model, where “everyone who works [t]here is an owner who not only participates in the day-to-day running of the business but who also makes decisions about the business.” Although Cheese Board was initially a traditional worker-owner hierarchy, Vanessa explained that the owners “wanted everyone to have an equal stake in the business since everyone was working equally hard.” This commitment to equality is not unique in the business world, as every company from Walgreens to Exxon advocates for equality. (Purportedly, at least). However, rather than raising wages or simply putting out half-baked statements on social impact, Cheese Board “decided to collectivize.” In one swift move in 1971, the cheese shop joined a mere 12% of US businesses which currently adopt the coop model.

This has interesting implications for the business dynamic, as workers not only “[make] pizza and bread […] but [they] do a thousand behind-the-scenes things, from ordering to payroll to cleaning the toilets.” In contrast to the specialized education system, Cheese Board empowers workers to practice multidisciplinary skills. In essence, every worker is their own Renaissance man or woman—equally capable of “order[ing] flour” as “craft[ing] policy.”

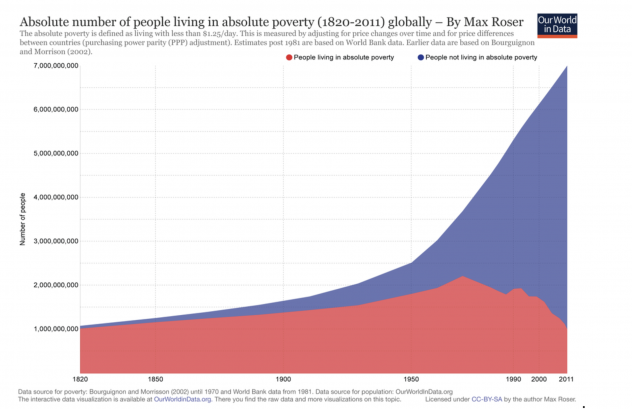

Collectivism, equal value for equal work…is it starting to sound familiar? While Cheese Board won’t be selling copies of Das Kapital anytime soon, the business represents a unique application of Marx’s economic theories. This emphasis on equal ownership presents a powerful challenge to most other businesses in the US, whose primary purpose is to generate stakeholder profit. Private companies historically improve standards of living, no doubt—look no further than the global decline in poverty as economic freedoms rise—but coops differ by prioritizing workers first.

Image source: Our World in Data

So, can collective models like Cheese Board’s coop create a better, more equal business world?

Greed, for Lack of a Better Word, Is NOT Good

Cheese Board completely flips the traditional worker-owner model on its head. At the coop, workers not only “[make] pizza and bread […] but [they] do a thousand behind-the-scenes things, from ordering to payroll to cleaning the toilets.” In contrast to the specialization of current job education, Cheese Board workers practice multidisciplinary skills. In essence, every worker is their own Renaissance man or woman—equally capable of “order[ing] flour” as “craft[ing] policy.”

While the coop equips workers with varied job market skills, the collective business environment also seems to improve worker psychology. Workers are “vested in the business both financially and emotionally,” even while most employees elsewhere feel detached from their business and colleagues. Since each worker has an ownership stake at Cheese Board, they’re more likely to put in that extra hour to keep the lights on. In essence, aligned interests fosters more worker commitment.

Vanessa’s experience seems to support this idea. For workers at Cheese Board, “there’s a lot of pride and satisfaction” since they own a portion of the business. Since worker satisfaction depends on the collective success of the business, not just private success or promotions, the business “tends to perform better.” Furthermore, by removing barriers between employees and business-making decisions, workers feel “happy, empowered, and cared for.” The evidence, both empirically and anecdotally from Cheese Board, is clear: enfranchised, positive employees improve productivity.

Thus, the collectivist environment at Cheese Board promotes selfless collaboration rather than greed. Although this may cause CEOs to think twice about their business model, there are also important philosophical implications. (I find economic philosophy interesting, sorry not sorry). For instance, while Adam Smith is famous for his invisible hand theory (the notion that society benefits from selfishness), the success of Cheese Board’s coop supports his forgotten, morally pure work The Theory of Moral Sentiments. In a more selfless picture, Smith wrote that a society and economy must promote sympathy for others—just like the worker environment at Cheese Board.

Just don’t tell Gordon Gekko from Wall Street, who wrongly proclaimed “greed is good.”

It’s Not All Sunshine and Rainbows

Cheese Board’s coop isn’t perfect, however. Specialization has its perks, as even Vanessa admitted that completing multiple roles can be “overwhelming.” Workers cannot simply focus on making pizza and bread, but instead also develop advertising solutions or facilitate hiring. Without a clear owner or hierarchy, it may be difficult to coordinate tasks or determine who delegates what.

To resolve these issues, Cheese Board “moved to a committee-based model in an attempt to facilitate decision-making and to share the workload more evenly.” Even for a smaller business like Cheese Board, there are simply too many decisions for the entire workforce to make collectively. No matter how you slice it (pun intended), centralization and specialization is always necessary to some extent.

These challenges lead coops to pursue wildly different business structures. There are “some [coops] with hierarchies, some that have workers who are not owners, some that divide the work differently, some that are employee-owned but not necessarily employee-run.” The varying structures and functions of coop systems across the US make it difficult to definitively conclude that Cheese Board’s model is the best. Coops may reduce inequality for some businesses, but reduce efficiency for others. Vanessa noted that “if a coop has 70 owners who need to make a decision about something, it’s usually a lot harder than if 20 owners had to make a decision about something.”

Ultimately, the application of Cheese Board’s coop model must account for the diversity of sizes, functions, markets, and workplace dynamics of different businesses. While coops have their benefits, economists, policymakers, and business leaders should be careful to avoid the “misconception that it’s all rosy and carefree in a cooperative.”

Model of the Future?

Despite these drawbacks, Cheese Board demonstrates that the coop model is a genuine solution to many current problems in the US economy. After COVID-19, workers quit their jobs in droves in order to pursue better opportunities with superior pay, benefits, and work culture. Even as the Great Resignation appears to plateau, the lingering effects of increased labor power remain significant. Union membership and worker strikes are on the rise, and industry leaders shouldn’t be afraid to be proactive and bold.

While adopting Cheese Board’s full-blown coop model may be too far for most businesses, embracing these more worker-centric policies could be a step in the right direction.

Vanessa put it best: “if we, as a culture, want to find ways to make capitalism work more compassionately and fairly, then adopting the coop model more and expanding it to different types of businesses is a good way to go.”

Featured Image: iStock

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.