DHOHA BARECHE – APRIL 6TH, 2023

EDITOR: ABIGAIL MORRIS

Introduction

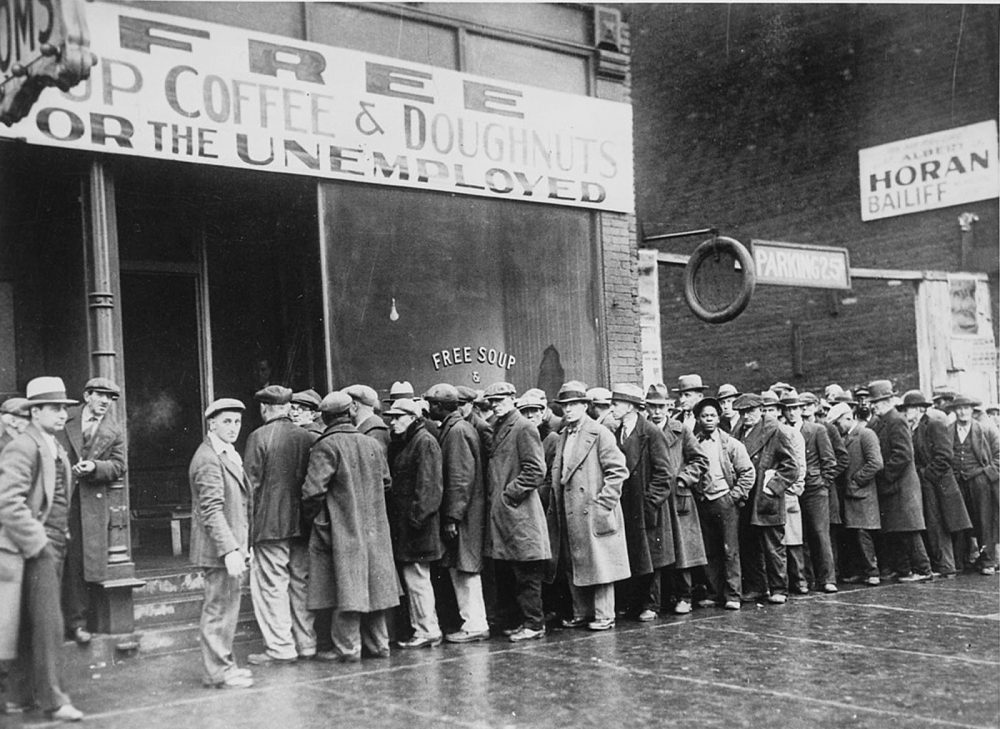

In 1934, U.S. Congress passed the National Housing Act to stabilize the housing market after its collapse in the Great Depression. During this economic downturn, the unemployment rate peaked at 29%, resulting in widespread homelessness and poverty across the nation. Nearly one in four American homeowners lost their homes to foreclosures and banks didn’t have enough funds to loan out mortgages. As part of an effort to mitigate the collapse of the housing market, the U.S. government established programs and policies to try and incentivize home ownership.

The first institution created after the passage of the National Housing Act was the Federal Housing Administration, whose goal was to provide mortgage insurance to lenders and make it easier for people to qualify for loans. In 1938, Fannie Mae was instituted as a government-sponsored agency with the purpose of stabilizing the housing market and providing liquidity. Initially, it only bought mortgages from the Federal Housing Administration then later included loans from the Veterans Administration. After it became privatized in 1968, it started buying mortgages from private lenders as well. Beginning in the 1980s, Fannie Mae started issuing mortgage backed securities– loans that are bundled together and sold to other investors.

Similar to Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac was established in the 1970s as a government-owned entity to expand the secondary mortgage market. The establishment of both of these institutions helped the housing market by making funds readily available for banks to issue mortgages. But after the 2008 financial crisis, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were placed under government control because they were at risk of insolvency for purchasing and insuring so many mortgages that were made to borrowers with poor credit histories who were unable to pay them off.

After decades of programs established by the U.S. government trying to rectify the housing crisis during the Great Depression, home ownership increased from 43.6% in 1940 to 65% in 1990. This growth continued to rise during the late 1970s and 1980s with the deregulation of the banking industry. Critics argued that the regulation of American banks made them less innovative and competitive compared to less regulated financial institutions. In the last two decades of the 20th century, there was a wave of deregulation beginning with the passage of the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act in 1980. This policy eliminated restrictions on the interest rate banks can pay depositors–that was once regulated by the government–and allowed the Federal Reserve to set reserve requirements in order to regulate the money supply.

In 1999, the Glass-Steagall Act, a significant piece of legislation that was passed during the Great Depression in order to regulate the financial system by separating commercial banks from investment banks, was repealed by the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act. Critics argued that the restrictiveness of the Glass-Steagall Act was “unhealthy” and allowing banks to diversify their activities would reduce risk. The repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act allowed commercial banks to engage in investment banking activities. It led to the consolidation of the banking industry and the formation of large financial conglomerates that were “too big to fail.” A notable example is the creation of Citigroup in 1998 that came about through the merger of Citicorp and Travelers Group.

With the deregulation of the banking industry came risky financial behavior. Before the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act, commercial banks were prohibited from using funds to invest in securities. But after these banks merged with other financial institutions, their range of services widened. Additionally, the lack of federal oversight spurred innovation which led to the creation of new financial instruments that were riskier. Although mortgage backed securities were created in 1968, they became riskier investments after deregulation because financial institutions started using subprime and alt-a mortgages to back them up. These loans were riskier because they were issued to borrowers with lower credit scores and incomes. The emergence of new types of mortgage-backed securities also made it difficult for investors to assess their risk because they were composed of home loans with varying credit qualities.

The deregulation of the financial sector coupled with risky financial instruments and lax lending standards fueled a housing bubble in the early 2000s as home prices rose due to high demand. More demand for home loans came about because the increase in subprime lending allowed borrowers, who typically wouldn’t qualify for a mortgage ,to easily finance a home. Although this created an avenue of homeownership for low-to-moderate income earners, it had major negative effects in the long run once it created a housing bubble in 2006 that eventually burst.

Subprime mortgages

Subprime mortgages are home loans issued to people who are considered to be “high risk borrowers.” They became popularized after the deregulation of the financial sector due to lax lending standards. There are three different types of subprime mortgages:

- Adjustable-Rate Mortgages (ARM): The most common subprime loan, Adjustable-Rate Mortgage borrowers start off with lower interest rates then it fluctuates based on the performance of one of three indexes it could be tied to.

- Extended-Term Mortgages: Unlike a conventional home loan with a 30-year repayment plan, Extended-Term Mortgages are paid over a long period of time–typically 40 to 50 years. Although a longer repayment schedule has lower monthly payments, borrowers remain indebted decades longer than others which results in great financial strain.

- Interest-only mortgages: Borrowers have the option to begin their mortgage by only paying off the interest on the loan within the first repayment period–usually between 3-10 years–or they can pay both the principal and the interest simultaneously. If a borrower opts for only paying the interest in the first repayment period, they have the option to refinance the loan when it’s time to pay off the principal.

Although subprime mortgages had high fees and interest rates, they appeared to be a good investment for borrowers. They offered an avenue to homeownership for households who were low income or had poor credit scores. Even if they struggled to make their mortgage payments, they had the option to refinance their homes or borrow more money to pay off their debt due to the ease of obtaining credit at low interest rates.

Investors made up for the risk of lending to poor borrowers by charging high fees and securitizing mortgage debt. Many of these subprime loans were pooled into private-label mortgage backed securities, which are securities with greater risk issued by investment banks and other financial institutions that were not backed up by government sponsored enterprises. Investors were protected from their losses because the expansion of subprime lending created higher demand for homeownership and increased prices. Higher house prices meant that if a borrower defaulted on their loan, the investor could still make a profit by selling the house. In 1994, credit default swaps were introduced as a form of insurance against the default of an underlying borrower. Lenders would buy a credit default swap from a third party who would agree to compensate them for the default of their investment. Moreover, there were several ways lenders and investors could transfer the risk of their financial activities, which eventually culminated in the Great Recession after housing prices came falling down in 2006.

The Burst of the Housing Bubble

By 2006, home prices started to decline because many homeowners struggled to make their monthly mortgage payments. According to the Federal Reserve, the mortgage market started experiencing issues in mid-2005 when the share of delinquent mortgages had increased from an average of 1.7% between 1979-2006 to 4.5% in the second quarter of 2008. Many mortgage defaults and delinquencies were particularly among subprime borrowers. As the supply of houses increased and demand decreased, house prices started to fall, as people found themselves owing more than what their house was now worth.

In 2007, the real estate market collapsed as the value of mortgage backed securities and derivative products were declining. This, coupled with falling house prices, led to a major credit crisis.

It’s important to note that American consumer debt at this time had been on the rise since World War II. The ratio of household debt to personal income increased from 31% in 1952 to 81% in 2000. So risky financial behavior is not just limited to home ownership, but other spheres of American life, which can be traced back to the relaxation of lending standards that made it both easier and accessible to take out loans for almost everything. But there are other psychological factors at play that can offer a deeper explanation as to why the financial crisis unfolded the way it did.

Why do people take out mortgages they can’t afford

The field of behavioral economics can provide great insight into major economic phenomena and illustrate why people are not always rational agents. Lax lending standards coupled with rising housing prices created a climate of optimism that deceived people into thinking that the housing market will continue to grow. Everyone wanted to get in on the action by investing in a home because it was accessible to do so–even if it meant taking out a risky loan they couldn’t potentially pay off in the long run. Behavioral economics suggests that people’s emotions and cognitive errors can influence their decisions. According to Hersh Shefrin, an economist at Santa Clara University, behavioral economics is “all over” the financial crisis of 2008.

-

- Herding Behavior: After the 2008 financial crisis, the term “herding” became widely used to describe the actions of investors who jump into risky ventures without much thinking because they are caught up in herd mentality. Although subprime mortgages issued to people with poor credit histories were risky, investors failed to see the potential dangers associated with it due to their increased demand coupled with rising house prices. The causes of herd behavior can be attributed to imperfect information, concern for reputation, and compensation structures.

- Anchoring: Anchoring in behavioral economics is the “subconscious use of irrelevant information” as a fixed reference point for decision making regarding a security. In the years leading up to the financial crisis, investors and borrowers relied heavily on rising housing prices to make their decisions. Even if subprime borrowers could not afford to take out a mortgage, it still seemed like a good investment because high housing prices meant that they could refinance their house if they couldn’t afford their mortgage payment. Investors anchored their risky decisions on the expansion of the housing market and the creation of new financial instruments that made it easier to transfer risk and obtain quick profit.

- Overconfidence: Overconfidence can be illustrated in banks’ relaxed lending standards and investors’ optimism regarding their mortgage backed securities. If investment professionals weren’t as overconfident, Shefrin said, then they would have better assessed the risk associated with holding large amounts of mortgage backed securities given that they were in a bubble. On the other hand, subprime borrowers were also overconfident in their ability to pay off their mortgage because housing prices were increasing at the time. It created a

- The American Dream: As illustrated through the policies passed and programs instituted in the early 20th century to promote homeownership, the idea of buying a house has long been seen as part of the American dream. Its history dates back to the founding of the U.S. as Thomas Jefferson saw that owning property was a symbol of freedom and success. Reinforced over the decades through economic policy, media, and culture the value in owning a home became deeply embedded into American society. So when relaxed lending standards allowed even those with lower incomes and poorer credit histories to take out a mortgage, it is not surprising that so many jumped to the opportunity despite the unpredictability regarding households’ future financial situation and ability to pay it off. According to Shefrin, “Homeowners who took out those loans simply wanted the American dream–they bought during a bubble on the assumption that housing prices are going up and will continue to go up.”

There is no single reason why the 2008 financial crisis unfolded the way it did, nor is there only one party to blame for it all. It was the culmination of various government policies that incentivized homeownership and a deregulated financial system that permitted excessive risk taking. It created an environment of overly optimistic lenders, borrowers, and investors who were hyperfocused on short term gains and ignored the long term risk of their financial decisions. With 8 million home foreclosures and more than 8 million jobs lost, the aftermath of the financial crisis had devastating consequences on all aspects of American life. Not only did the Great Recession negatively affect the global economy, but it also shattered the idea of economic man as a rational agent. The field of behavioral economics helps us understand how non-rational behavior contributed to the financial crisis and the important role cognitive errors play in decision making.

Featured Image Source: Monetary Musings

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.