Writer: Mariana Escobar | Editor: Ava Inman

Introduction

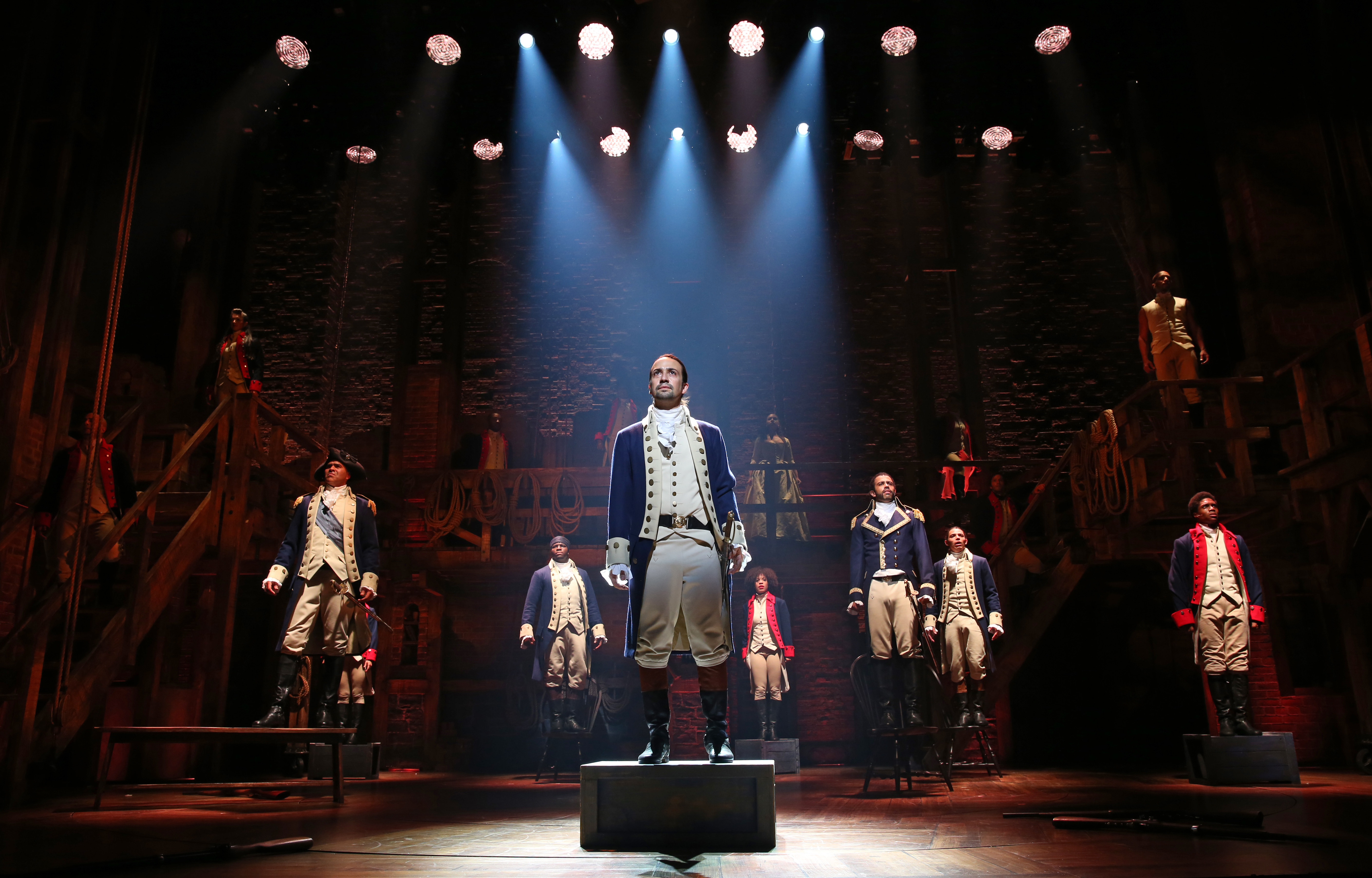

The phrase, “Don’t be shocked when your history book mentions me,” must be one of the most confident and ambitious statements uttered under the spotlight. However, in Hamilton: An American Musical, this expression is an understatement when considering the economic foundation Alexander Hamilton almost single-handedly constructed for the United States. This acclaimed hip-hop musical, written by Lin-Manuel Miranda, gained fame by narrating Hamilton’s journey from his humble beginnings in the Caribbean to his achievements in early America. At its peak in 2016, Hamilton grossed about $1.5 million per week in ticket sales as prices reached $5,000 on third-party sites.

Due to the musical’s rapid rise in popularity and its 11 Tony Awards, thousands have reviewed and analyzed it. Yet, few have considered this seemingly patriotic and capitalistic narrative from a Marxist standpoint.

Before conducting a holistic analysis of the musical, it’s crucial to first examine the tools and perspectives we’ll use in the process. The study of critical theory involves several critical theories, all of which, when applied to literature, help analyze the messaging within any text, subliminal or direct. One of these theories, Marxist criticism, dives into the socioeconomic structure constructed within any literary piece, and examines its effect on the individuals within it. Therefore, when applying Marxist criticism to a text, the main goal is to evaluate whether the text follows a capitalist agenda, reinforces a Marxist agenda, or is ideologically conflicted. Using this framework, one can conclude the text’s ultimate argument regarding class struggle.

This theory also has ideologies, such as classism, rugged individualism, and conspicuous consumption. In Critical Theory Today, Lois Tyson defines these as belief systems that “promote repressive political agendas and, in order to ensure their acceptance among the citizenry, pass themselves off as natural ways of seeing the world…” They are mechanisms to maintain the hierarchy of power; their representation in literature ultimately guides a reader in pinpointing the text’s agenda. In Hamilton: An American Musical, specifically, Alexander Hamilton’s rugged individualism and ambition are both key to his historic accomplishments and, simultaneously, his demise. This American story–turned–famous Broadway show is not one of success and the American Dream; rather it is a glorifying narrative of a man’s egotistical capitalist ambition.

The Founding Father’s Foundation

In the Caribbean, Hamilton grew up in poverty and isolation. His father left the family “debt-ridden” when Hamilton was ten years old; his mom died of disease; and the cousin he later resided with committed suicide. The opening musical number, “Alexander Hamilton,” highlighted that this non-stop adversity ultimately fueled his infamous steadfastness and vocation. After mastering his writing skills, his amazed town came together to buy him a ticket to New York; his grit and determination became his golden ticket to the United States. In addition to showcasing his ambition, Hamilton’s socioeconomic climb to the new nation introduces classism—the division of people based on their economic status. This separation ingrains into one’s mind that one’s value as an individual directly correlates with one’s social class. Throughout the course of the musical, Hamilton is driven by a need to prove himself—something he can only seemingly do by climbing the socioeconomic ladder. Hamilton’s need to ascend socioeconomic ranks perpetuated the notion that the only way to make a name for oneself is through heightening one’s social standing.

Hamilton thus believed he needed to acquire an influential position in the United States, so he channeled his drive into the colonial efforts of the Revolutionary War. Through labor and wit, he became George Washington’s trusted aide, ultimately positioning himself for a place of future influence. At the peak of Act I, “The Battle of Yorktown,” the revolutionary victory and Hamilton’s new-found authority as a war general brings to fruition his American Dream. It is worthwhile then, to consider the nebulous, often troubling notion of the American Dream. In The Problems of the American Dream: False Hopes and Hurtful Judgements, Elizabeth Murray defines the idea of the “American Dream” as an “origin myth,” as it “[spreads] the belief that hard work in America leads to monetary success for all citizens of every race and class in which one is born.” It perpetuates this notion that every American has an equal chance; thus, it takes a colorblind approach and indirectly contests the notion of systematic inequality, or that American capitalism naturally favors some over others. As aforementioned, America’s social structure is one defined by class; therefore, these ideas can’t exist in tangent. Therefore, at this point in the musical, the storyline asserted that the American Dream was an achievable concept; and this story came to reflect the the capitalistic idea that hard work will always result in success.

Hamilton’s Demise

In “Non-Stop,” the raps encapsulated Hamilton’s next seven years, characterized by relentless hard work in pursuit of greater power, revealing his rapid conspicuous consumption mindset. Conspicuous consumption, the act of overconsuming merely to display one’s wealth, is evident in the song’s descriptions of Hamilton’s unbelievable work pace: “Why do you write like you’re running out of time?… Every day you fight like you’re running out of time.” This conveyed Hamilton as someone driven by an insatiable need for achievement as if he was stuck in a relentless frenzy for success. Hamilton’s unique determination slowly became what he was known for, and his desire for increasing levels of recognition and power seemed insatiable.

Hamilton’s non-stop ambition consequently brought his rugged individualism to fruition. This ideology promotes and romanticizes the notion of an individual who bravely, and with perseverance, pursues their needs and goals; “keeping the focus on ‘me’ instead of on ‘us,’ [and working] against the well-being of society as a whole…” At the climax of his career, George Washington, newly elected as president, asked Hamilton to help him lead as the first Secretary of the Treasury. While his loved ones criticized this and told him to ease his workload to focus on his relationships, Hamilton jumped at Washington’s offer. This entire scene reflected his restless and selfish mind; after all, he was working this hard solely for himself, and thus became the epitome of rugged individualism.

Ultimately, this same rugged individualism, conspicuous consumption, and single-minded purpose drove Hamilton to carve his place in America’s formational history, and consequently created his fatal enemy: Aaron Burr. At the end of the musical, Burr realized Hamilton had been a consistent impediment between himself and his goals; Washington chose Hamilton over Burr as his right-hand assistant, Hamilton became the political figure Burr always longed to be, and Hamilton kept Burr from the presidency when he publicly endorsed Burr’s opponent. For all these reasons and others, Burr challenged Hamilton to the infamous duel that felled him. Of course, Hamilton, who valued his legacy more than his life, accepted.

In Hamilton and Burr’s duel, we learn that Hamilton’s egoist drive to establish a name for himself stemmed from his fear of a forgotten legacy. . What had seemed a fear of death, had actually truly been a fear of oblivion, of being forgotten by an unforgiving history. Hamilton wanted his legacy to be the foundation he left behind for America, that “great unfinished symphony.” When Burr ultimately shot Hamilton, he got left behind in time; and yet it was his own, parallel desire to build a legacy that put him there. His selfish ambition, an amazing quality at first, was his hamartia; he was his biggest enemy and manufactured his demise.

“Alexander Hamilton: An American Musical”

In the closing song, “Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Tells Your Story,” the musical painted Eliza as the ultimate hero of this narrative, as she was the one who succeeded in saving Hamilton’s treasured legacy. After Hamilton’s death, Eliza helped fund the Washington Monument, interviewed soldiers who fought with Hamilton, and continued to fight against slavery in his name. She even worried that all this wouldn’t be enough for Hamilton’s name to be remembered. In the last scene of the musical, Hamilton held her hand and directed her upstage to face the audience alone as she let out a tearful gasp. As Eliza stepped towards the audience, the fourth wall broke, and she saw the hundreds of people gathered to watch Hamilton’s story because of her hard work to keep his memory alive. After all, the musical isn’t called “Alexander Hamilton: An American Musical” but just Hamilton: An American Musical. This story of success is for Eliza Hamilton, not Alexander; we can attribute Hamilton’s dream of a bright reputation that has been remembered for generations to Eliza.

Why, then, does the musical present such a positive portrayal of Alexander Hamilton’s life? Well, it is the same reason why many of these “die-hard” Hamilton fans would’ve never bothered to look into Hamilton’s accomplishments if it weren’t for the musical: Hamilton’s life did truly end on a low, which is exactly what the musical doesn’t want the audience to perceive.

By deliberately downplaying this, the musical focuses instead on his ambition and accomplishments to leave the audience with a more inspiring impression of his legacy—one of hope and perseverance. Through a Marxist lens, it wants to convey the false consciousness of a successful “rags to riches” American Dream story, meant to be an inspiration for current and future America. This false consciousness ideology describes the empty-promised mindset one has when believing they need to sacrifice their life to achieve their American Dream and live “happily ever after,” which is the main message audiences are supposed to obtain. However, through Eliza, the musical contradicts this theme, as she achieved Hamilton’s goal of a powerful legacy without being tied down to these harmful ambitions and giving into the false consciousness, making this a conflicted text. Therefore, a more responsible moral that can derived from the story is that excessive ambition can lead to self-ruination. The glorification of Hamilton’s traumatic, overly ambitious life can ultimately bring about a generation of blinded and naive rugged individualists through its seemingly innocent, catchy raps.

Featured image by Joan Marcus