SETH BERTOLUCCI – MARCH 9TH, 2018

When the economy suffers from a deficit in aggregate demand, you’ve got to juice it up. Spend. Spend a lot. That’s been the public policy trajectory since the end of World War II, ever since the government failed to do this from 1929-1931 and created our favorite economic supervillain, the Great Depression. In the words of the renowned John Maynard Keynes, governments should “spend against the wind,” ensuring responsible fiscal restraint during booms and debt financing during busts.

Which brings us to today. Is the economy suffering from output below potential? Do we have a deficit in aggregate demand? The Republican tax reform plan, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, is expected to create $1.45 trillion in additional debt over the next 10 years. Recently, a budget deal reached between Democratic and Republican leadership provides an extra $500 billion in funding over the next two years for military and domestic programs, and once that two years is up it’s pretty unlikely that lawmakers will vote to end those increases. Surely, the consensus must be that the American economy is in desperate need of massive stimulus? The economic data tells a different story.

Things are actually pretty damn good. Unemployment rests at 4.1%. Although stagnant wage growth is a long-term structural trend of the past 40 years, wages have grown in real terms from 2007-2017 at their fastest rate since the late 1970’s. Despite a recent correction, the stock market still teeters at record highs. GDP growth has consistently chugged along around 2% a year since 2009. The majority of economists believe that the economy is at or near full employment. And the latest inflation news showed a notable 0.5% rise in the Consumer Price Index in January, with year over year inflation getting increasingly close to the Fed’s 2% target.

Given these respectable fundamentals, widespread economic stimulus right now will likely push inflation higher as increased government spending and huge tax cuts boost prices. The Federal Reserve, in turn, will raise interest rates faster than previously expected. This might eliminate many of the short-term gains from the Republican plans, as higher interest rates begin to slow growth. Further, as the government borrows trillions more than previously expected, investor demand for bonds may crowd out the private sector economy, as those seeking safe and reliable returns opt for government debt that pays increasingly higher coupons. Rapid interest rate rises could indeed be the death knell to Wall Street’s post-recession bull market. Higher rates can also massively drive up the cost of the government’s own interest payments on the debt, an already gigantic part of government spending. Last year’s payments alone totaled $276 billion.

But how does Congress’ latest spending binge tangibly affect federal finances? According to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, the Republican tax bill will balloon the federal debt to 98-100% of GDP by 2027, compared to 91% by 2027 under prior law. The budget deal will further increase the debt to 105% of GDP if its temporary provisions are made permanent, something quite likely given politicians’ phobia of spending cuts. The deficit, assuming temporary tax breaks and spending increases are made permanent, is estimated to reach $1.2 trillion by 2019 and a whopping $2.1 trillion by 2027.

But what are the risks of running up such a massive debt in the long term? Detractors might point out that the United States ran up a debt-to-GDP ratio of 112% during World War II. Although this money was rapidly paid back in the following decades, that debt bubble actually preceded 30 years of the most rapid and equitable growth that the United States has ever experienced. Critics can also point to Japan, who tops the world at a staggering 234% debt-to-GDP ratio. Despite long-term stagnation and malaise since a severe recession in the early 90’s, the Japanese economy has remained quite stable. In fact, Japan is not even plagued by the inflation that would be characteristic of runaway debt, but has actually been fighting deflation for the last 25 years.

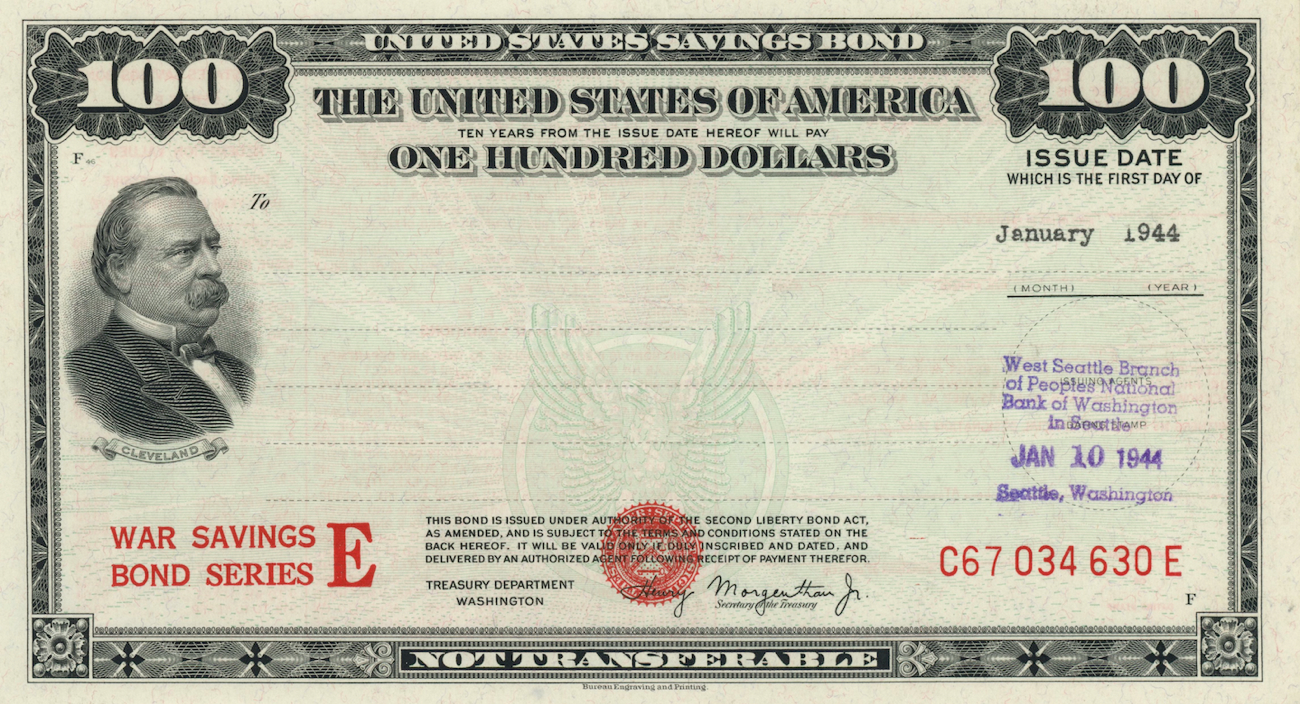

Yet both arguments are flawed. During the Great Depression and World War II, America’s debt staggeringly increased due to the proto-Keynesian policies of the New Deal combined with the tremendous cost of financing a world war. American debt during peacetime has historically never even come close to the level we see today. Post-1945, the government rapidly repaid its creditors (mostly American citizens who had bought small war bonds) so that debt-to-GDP stayed comfortably under 30% until the early 1980’s. In the case of Japan, nearly a quarter of government expenditure is devoted to servicing the debt. And ratings agencies across the world have downgraded Japanese debt over the years, further increasing the cost of borrowing. Indeed, at a time when Japan requires economic stimulus to finally propel them out of deflation and low growth, the cost of their debt is undeniably holding the nation back.

In the short term, increasing spending while cutting taxes might help Republicans with political popularity before the 2018 midterms, but this type of fiscal policy will deliver a minor boost in growth while driving up inflation and interest rates. Over the next 10 years, the government will need to borrow 14% of the value of our GDP to pay for these expensive new programs. That’s not exactly much bang for our buck.

In the long term, recklessly borrowing pushes us towards a confidence crisis in our government’s ability to pay people back. There is no fixed point at which investors lose faith in US bonds, but in Greece this crisis occurred at around 180% of debt-to-GDP. Most scarily, in the case of the European debt crisis, nations such as Portugal, Spain, Italy, Greece, and Ireland all had austerity forced upon them exactly when their economies required massive economic stimulus, not huge cuts in spending. Once individuals no longer trust the American government will repay them, the US could be faced with a debt crisis and investor-imposed austerity at the worst possible time.

And continuously issuing trillions in bonds creates artificial demand for the dollar, thereby creating a systemic undervaluation of foreign currencies like China’s Yuan. For an administration supposedly concerned about the trade deficit, it is certainly ironic that Trump has pursued policies so beneficial to China’s exporters. The American people will have Congress to thank for the victory of short-term political gimmicks over long-term economic health.

When the next recession hits, will the world’s investors have enough faith in our fiscal stability to once again loan us trillions of dollars at favorable interest rates? At what point do people stop believing that American government treasuries are the safest in the world? As our debt rockets past 100% of GDP, when will we finally consider the ramifications of our actions? Congress continues to ignore Mr. Keynes, spending both with and against the wind. Surely to follow is at best economic malaise, and at worst economic calamity.

Featured Image Source: Wikipedia

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of The Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California at Berkeley in general.