RAMYA SRIDHAR – NOVEMBER 3RD, 2023

EDITOR: FELIX ZHANG

On the 4th of May, 2018, a Keralite woman by the name of Sheeja Daas in Muscat, Oman jumped from the balcony of her employer’s house, allegedly in order to escape a beating. The 38-year old female claimed to have been chased by the lady of the house, all the way to the second floor, from where she saw no other recourse beyond jumping. She broke both her legs and was paralyzed from the waist down.

Her employer—a police officer—responded to the incident by attempting to send her back to Kerala, India, with neither the rest of her family nor her due compensation. Ultimately, it was the Indian Embassy that paid for tickets to send her husband and her two children home with her—though, according to her husband, the issue of her compensation was never raised.

During the course of her employment, Sheeja claims to have endured physical, verbal, and financial abuse; over the course of a mere two years, she was starved and beaten to the point where she lost nearly 40 pounds. Her employer would put money in her account monthly, only to withdraw the same amount later that day. He claimed he would pay her by the end of the year, a promise that remained unfulfilled.

Sheeja’s treatment was paid for by the social workers of Oman. She claims that neither her nor her family’s life will ever be the same again. 5 years later, the story is no less horrific.

Bonded labor has existed for centuries—its origins can be traced to the end of the Transatlantic trade, where indentured servitude emerged as a new way to harness and justify cheap labor. In essence, bonded labor, also referred to as debt bondage, or simply as bondage, is when workers attempt to pay off debts through cheap, often uncompensated labor. As per 2022 estimates,one-fifth of all forced labor occurs through debt bondage. This form of forced labor is especially relevant in the context of the Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf, also known as the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). It is composed of six Arab countries—Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. Many of the most grotesque cases of bonded labor reported have occurred with migrant workers employed in the GCC. Residents of various South Asian countries, such as India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan, are constantly seeking better paying blue collar jobs within the GCC countries.

While these job opportunities in the Arab Gulf initially appeared to be pathways for South Asian individuals and their families to escape poverty, with an overwhelming supply of labor that exceeded demand, labor conditions quickly worsened and wages diminished. Additionally, the hiring processes can often be misleading, unclear, or manipulative—these abuses range from borderline incomprehensible contracts to blatant lies about payment, housing conditions, and contract lengths. Nevertheless, despite deteriorating conditions, many of these migrants still find that they can earn more in the Gulf than in their home countries. And the wage discrepancy encourages them to tolerate even the worst of conditions.

At the center of this unjust labor network, we see the kafala system. The kafala system requires that migrant workers have a sponsor, a figure that usually has substantial control over the worker’s legal status. For most workers, this sponsor is their employer, which only further exacerbates the power disparity between employers and employees. Between a monopsonic market and the kafala system, employers have stripped workers of their basic rights and ability to lobby for better working conditions, creating a dangerous ‘ownership’ dynamic reminiscent of slavery.

A number of industries remain dependent on this labor system—industries that the rest of the world tends to depend on for imports. For example, take sandstone—it is often used as a building stone or as a source of metallic ores, and can even be refined into a glass-like material. The sandstone industry is considerably large, and a key player in the field is India—specifically, the state of Rajasthan.

Rajasthan produces 90% of Indian sandstone. However, sandstone production in Rajasthan has been subject to a number of human rights violations, including bonded labor, child labor, and general worker maltreatment. The supply chain system, which consists of multiple stages of refinement, is unregulated, opaque, and consistently secretive. In the quarries, where relationships between worker and employer are blurred and often unprofessional, the workers lack protective legislation or any system of employer accountability against injury or loss. As a result, many miners face serious injuries and long-term diseases, due to a dangerous lack of occupational safeguards.

Rajasthan’s sandstone industry is filled with secrecy and abuse, yet the rest of the world, normally quick to denounce such unethical forms of labor, turns a blind eye. As of 2020, the U.S. ranks fourth in its importers.

By Indian law alone, Rajasthan’s sandstone chain would be considered unlawful. The U.S., which prohibits the use of imported goods procured through child or forced labor, would also consider India’s sandstone industry a violation. However, the nature of bonded labor, with its power imbalances and lack of transparency, distort the ability of government agencies to assess workplace conditions.

As aforementioned, bonded labor was made illegal in India in 1976—the Bonded Labour System Act established that persons convicted of enforcing bonded labor would be sentenced to at most 3 years in prison and fined Rs. 2000. Though this law succeeded in rescuing and rehabilitating thousands of bonded laborers, it was not clearly insufficient in eradicating the issue. This is partially due to the fact that, in the 1990s, there was a huge effort to downplay the pervasiveness of debt bondage. Much of the original intent to address bondage had come from grassroots social movements, as opposed to governmental institutions—so, as the momentum behind those movements declined, so did the state’s sense of obligation to address the issue. Additionally, many victims report having not been offered proper rehabilitation resources due to corruption and negligence. Many victims were also overlooked by state efforts — for example, since many of the employer-employee contracts were addressed specifically to men, who were seen as the head of the house, women were often denied the same state benefits and release certificates. As a result, many industries still use bondage to source cheap labor.

The silk trade, like the sandstone industry, is filled with corruption. Despite being valued at $14 billion globally, many employers in the silk industry pay their workers less than $3 a day. Workers, who boil silkworm cocoons and remove the silk threads—painstaking labor under harsh, injurious conditions—are paid a pittance to work long hours and endure employer harassment.

These stories of harassment aren’t difficult to find. In a silk factory in Sidlaghatta, Karnataka, a young woman named Naseeba, and her mother, Hadia, are forced to work nearly 11 hours a day to pay off loans. As per the young girl’s testimonial, her employer approached Hadia and told her that, should she fail to repay her debts, he would force her to sleep with a rich man.

The bonded labor industry is rife with similarly chilling accounts. One of the most prominent stories in debt bondage is that of Kasthuri Munirathinam, a Tamilian woman who alleged to have not been paid, fed, nor treated properly while working for a Saudi household. She had her arm chopped off by her employer when she went to the authorities to complain about her working conditions. According to her sister, Vijayakumari, Kasthuri had accepted employment in Saudi Arabia in order to repay her family’s debts.

“But she was not paid, she was barely given enough to eat and not even allowed to speak to her family … Now she only wants to come home,” Vijayakumari said.

Within the GCC, there are over 2.5 million domestic workers, most of whom are female migrants from Asia or Africa. Many of these women endure physical, verbal, and sexual abuse, working in borderline intolerable conditions. And while each of their stories remain different, the common themes of abuse, harassment, and intolerable working conditions appear again and again.

Situations only worsened under COVID-19. In order to offset the ramifications of a slowing economy, many states in India relaxed labor regulations. Rajasthan increased its workday from 8 to 12 hours. Similarly, Punjab and Gujarat amended their legislation to include 72 hour work weeks. Ultimately, the economic burden of the pandemic fell heavily on blue collar workers.

For many, reintegration from this brutal form of modern slavery can be mentally, physically, and financially challenging. In 2016, India announced its target of rescuing 30 million workers from debt bondage and increasing their compensation to ten times its original. However, by 2019, not a single person had received their dues, and 60% of those who had been rescued find themselves back in debt bondage. This is also exacerbated by the fact that workers often do not receive their compensation unless their employer is convicted, which can take years.

Tina Jacob, associate director of the International Justice Mission, asserts that responses to debt bondage have to be immediate in order to be lasting. According to Jacob, “When bonded laborers are rescued, they are in shambles. They should get aid within the first 30 days, or they just become vulnerable again.” And yet, the system of reintegration is complicated by backlogged cases, inefficient structuring, and the sheer scale of bondage victims.

Bondage perpetuates cyclical poverty. The root causes of debt bondage aren’t just predatory industries and individual cruelty—it’s a lack of social mobility, the prevalence of poverty, and the absence of labor unions and legal protection for workers. These root causes are what lead to the stark power discrepancies between workers and employers—until these issues are addressed, bondage labor will continue to remain prevalent among workers from developing nations. It’s the role of both domestic and international governments to ensure workers are treated fairly and to persecute individuals and organizations perpetuating bondage. Only when the root causes of forced labor and those continuing its practice are eliminated can we begin to pave the road towards more balanced labor relationships.

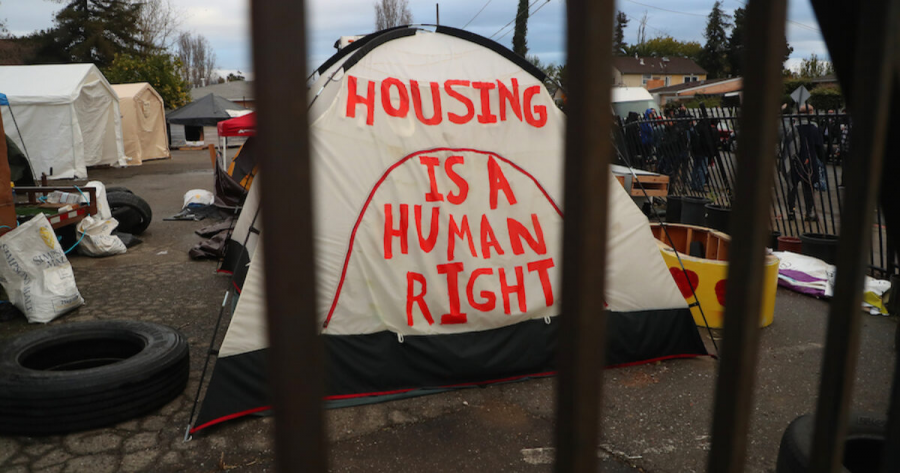

Featured Image Source: Anti-Slavery International

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.