VANESSA THOMPSON – NOVEMBER 18TH, 2019 EDITOR: SHAWN SHIN

Nearly everything we consume is wrapped in plastic, and little to no thought goes into their proper disposal. However, the frequent use and volume of plastic is resulting in an environmental crisis. Today, 91% of all plastic goes unrecycled. Every year, 12 million tons of plastic are conveyed into our oceans, either haphazardly or deliberately, resulting in numerous islands of trash; the biggest island being larger than the state of Texas. These increasing numbers of plastic goods are causing an environmental crisis. The lack of financial incentives for proper disposal results in plastic being discarded carelessly. To find monetary value in what is wasted, we must implement economic incentives to encourage reuse.

Background on the Issue:

The daily plastic packaging consumers use surmounts to an overwhelming supply of plastic waste. In the United States alone, over 137.7 million tons of waste is sent to landfills annually, an amount equivalent to about 377 Empire State Buildings. However, less than ten percent of total produced waste is recycled. The majority of waste that is not recycled ends up in landfills or in our ecosystems, such as rivers that lead to the oceans. What is dangerous about plastics in the oceans, is that they do not decompose; instead, plastics break down and become smaller pieces over time. As they break down, they are easier to be mistaken for food by fish, often resulting in deaths of marine organisms. These small pieces of plastic that cause havoc on ecosystems are referred to as microplastics. The enormous buildup of them in the ocean has created scattered islands of floating plastic. Microplastics make up 94% of the plastic in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, which is the largest garbage island in the world.

Although many individuals don’t face plastic pollution as a daily concern, the health implications for humans are alarming. As Scientific American reported, “Ingested microplastic particles can physically damage organs and leach hazardous chemicals—from the hormone-disrupting bisphenol A (BPA) to pesticides—that can compromise immune function and stymie growth and reproduction.” It is estimated that people have an average intake of 50,000 plastic particles per year from food and other consumables. In addition, there are studies that indicate plastic consumption can increase “[the] risk of birth defects, metabolic disease, and other health problems.” Even if plastics do not end up in the ocean, they can break down in landfills or natural spaces. Once they turn into microplastics, they can seep into waterways and subsequently contaminate drinking water supplies. In one glass of water, there can be thousands of microplastics.

Microplastics threaten the communities that depend on marine resources. A tenth of the world’s population directly depends on fisheries to survive, and most of the world’s population indirectly relies on ocean resources. Without healthy fish stocks, our world economy would be dramatically impacted. Oceans alone contribute $1.5 trillion to the economy each year.

PET Plastics versus Alternatives:

The natural resources on which we depend are severely impacted by plastic pollution. Thus, we have strong incentives to ensure that plastics be safely disposed of or reused. Unfortunately, cutting out plastics are not really feasible, as plastics still have a tremendous economic benefit to our daily lives. Therefore, innovation towards recyclable plastics and better waste management are the only two realistic solutions. One of the most recyclable and valuable plastic materials is polyethylene terephthalate, or also called PET, which is the material used for most water bottles. PET can be recycled, broken down and re-made into polyester fibers (polyester should ring a bell as the material in many fabrics). In other words, PET can be recycled and, theoretically, made into new products forever. PET may start off as a water bottle, then made into a t-shirt, then a rug, and so on.

Products like this are a part of a hypothetical model called the circular economy, meaning that the same resource can stay in the economy and have value. As Peter Seeger, a sustainable fashion icon, states, “If it can’t be reduced, repaired, rebuilt, refurbished, refinished, resold, recycled or composted, then it should be restricted, redesigned or removed from production.” This movement towards the circular economy has incentivized various industries to produce packaging using PET instead of less recyclable plastics.

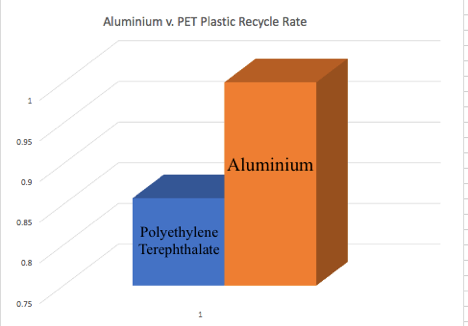

An ever-present concern is that PET can turn into microplastics if disposed of improperly. Therefore, other environmentalists may suggest alternative solutions, such as switching to aluminum containers to avoid plastics altogether. This argument does have some merit, because the rates of recycling for aluminum is higher than those for PET, as the graph below shows (compiled from data coming out of EU nations, Canada, and the US states that had available information). However, this is only true because using virgin aluminum is so expensive that recycling is almost always the cheaper solution. In addition, aluminum only accounts for one percent of household recycling. Lastly, PET emits minimal carbon dioxide in production relative to aluminum and glass―one half and one-fourth of the emissions of each, respectively. For frequent usage, PET may be a more sustainable solution, even with the mismanagement risk.

Data from here | Graph by Vanessa Thompson

PET Plastics and Deposit Incentives:

All recyclable plastics are marked with a number—printed within the recycle symbol—between one and seven based on their level of recyclability. One is the most recyclable plastic, and seven is the least. In other words, plastics marked with seven can only be recycled and turned into another useful plastic a few times before needing to be thrown out. More and more companies are switching to the number one plastic: PET. Its cost-effectiveness and durability are leading companies to switch quickly.

Similar to aluminum, the value of plastic must be high to incentivize reuse and recycling. These values subsidize the costs of transporting, cleaning, sorting, and recycling PET plastic. Since the value of plastic is often too cheap to be worth the cost of recycling, deposit schemes are vital for increasing recycling rates. Most PET becomes excess waste sent to landfills, illegally dumped, or burned, impacting the health of individuals and the environment. According to Greenpeace, “this huge increase of imports has caused a drop in prices for recyclable collected locally, making it economically unattractive to recycle.” In essence, the key to increasing recycling is increasing the value of PET.

Deposits have proven to be a successful way to add value to PET and consequently increase recycling. Based on policy initiatives often funded by local and state governments, deposit schemes place a fee on the bottle, which can be redeemed if returned to the retailer. States like California have a five-cent deposit on most PET, aluminum, and glass items. These initiatives are highly effective and can increase recycling rates significantly: “In states without either stringent recycling laws or bottle deposit laws, respondents recycled 4.4 bottles out of 10. In states with deposit laws and stringent recycling requirements, respondents recycled 8.3 out of 10 bottles.” European nations that are striving to meet the EU’s new plastic waste standards are implementing deposit laws or updating their legislation. Although only ten states in the US have bottle bills, which include deposit schemes, almost all EU nations have deposits. These deposit schemes positively impact recycling rates, although they do not dictate the exact rates of recycling.

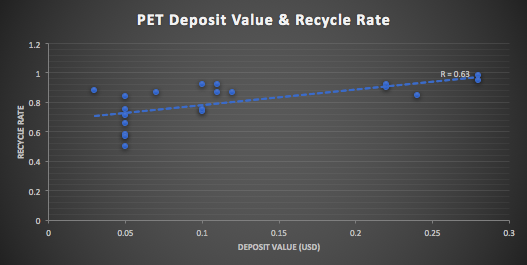

The figure below contains data from ten European nations and ten American states that have the most publicly available information about recycling policy. The correlation between the additional deposit value placed on a PET container and the region’s rate of recycling is significant. The horizontal axis represents the deposit value of PET plastic in USD, and the vertical axis displays the recycling rate of PET plastics. The correlation coefficient between deposit value and recycle rates is high (r = 0.63), considering that cultural, legislative, and operational differences across regions play a large role.

Data from here | Graph by Vanessa Thompson

Deposits remain the most effective way to increase recycling according to most academic literature, policy initiatives, and research institutes. Their success is due to the financial incentive consumers, and retailers receive. Retailers pay distributors a deposit for each can or bottle purchased; the retailers collect those deposits from consumers who purchase beverages. The retailer reimburses the deposit to the consumer and recovers the money from the distributor, often with a small handling fee included. Deposits give retailers an incentive to place recycling bins and promote environmental education programs in their stores.

A number of states found success in increasing deposit schemes. In 2018, Oregon recycled 90% of its bottles, a statistic notable for the US. After increasing their deposits from five to ten cents, Oregon increased its recycling rate for PET from 64% to 90% in only two years. Policy directly influences recycling rates, enabling individuals to gain greater access to sustainable choices. In addition, Oregon’s deposit schemes policy programs have accompanied the monetary incentive to enable greater access. Their BottleDrop service allowed shoppers to “drop off their bottles to be counted and credited to their accounts.”

Programs that emphasize economics over altruism can influence the most significant environmental progress. The source of our plastic crisis is based on two main factors: a lack of environmental awareness and financial incentives. As the scale of the plastic crisis grows, our strategy for urgent action mustn’t solely address cleaning up our mess, but finding sustainable incentives for long-term success. By increasing the value of invaluable goods, we can generate greater demand for recyclable plastics like PET.

Plastic-filled oceans and litter-covered natural environments can illustrate a daunting crisis. Many of us don’t even know the scale of the issue, much less the solution. Plastic products are often blamed for creating and supporting a throw-away society based on greed and little regard to the larger picture. However, when managed well, plastics can be recycled and made (and remade) into valuable products, which is sustainable and economically desirable. In order to make this happen, it is necessary to prioritize economic solutions for a step towards sustainability. If we want to address these threatening environmental forecasts successfully, we must seek profit-based models, such as deposit schemes, that empower responsible waste management to turn rubbish into a trillion-dollar industry.

Featured Image: Sensible Sustainability

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.