PETER ZHANG – OCTOBER 19TH, 2020

EDITOR: PEDRO DE MARCOS

Soaring costs are a recurring headline in American healthcare, and the centerpiece is the rising price of drugs. A GoodRx report from this September found that the cost of prescription drugs has increased by 33% since 2014. Compare this to the cost of home nursing or dental services, which have increased by 23% and 19%, respectively.

Pharmaceutical companies have continued to raise prices amid the COVID-19 pandemic. A report from Patients for Affordable Drugs, an organization dedicated to lowering the cost of prescription drugs, found that of “the 245 drugs with price increases, 61 are being used to treat COVID-19, 30 are in use in coronavirus-related clinical trials, and 20 are commonly administered in hospital ICUs.” One company, Astrazenika, hiked prices by an average of 6% this year, despite receiving over $1 billion in federal funding to develop a coronavirus vaccine.

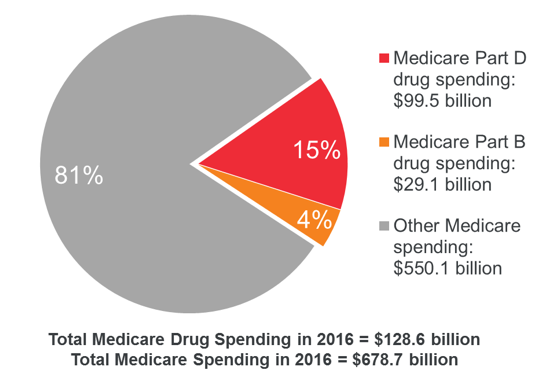

Price hikes are felt hardest by Medicare, the federally funded insurance program for the elderly. Medicare Part B provides coverage for inpatient drugs while Part D subsidizes prescription drugs. While both parts face high drug costs, Part B prices are 1.8 times higher than other countries. In fact, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services attributed a 7% increase in 2020 Part B costs to physician-administered drugs. Together, Parts B and D consistently spend over $100 billion a year on pharmaceuticals.

Image source: MedPAC

Medicare costs are high because the program is unable to negotiate prices with drug manufacturers. The noninterference clause in the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 stipulates that the government may not “institute a price structure for the reimbursement of covered part D drugs.” Instead, the prices of Medicare drugs are calculated from the prices negotiated by private insurance companies. However, no single insurer represents more than a quarter of Part D participants, so private insurance companies have less individual leverage to bring down prices. As a result, manufacturers can charge unjustified high prices, particularly in the absence of competitors.

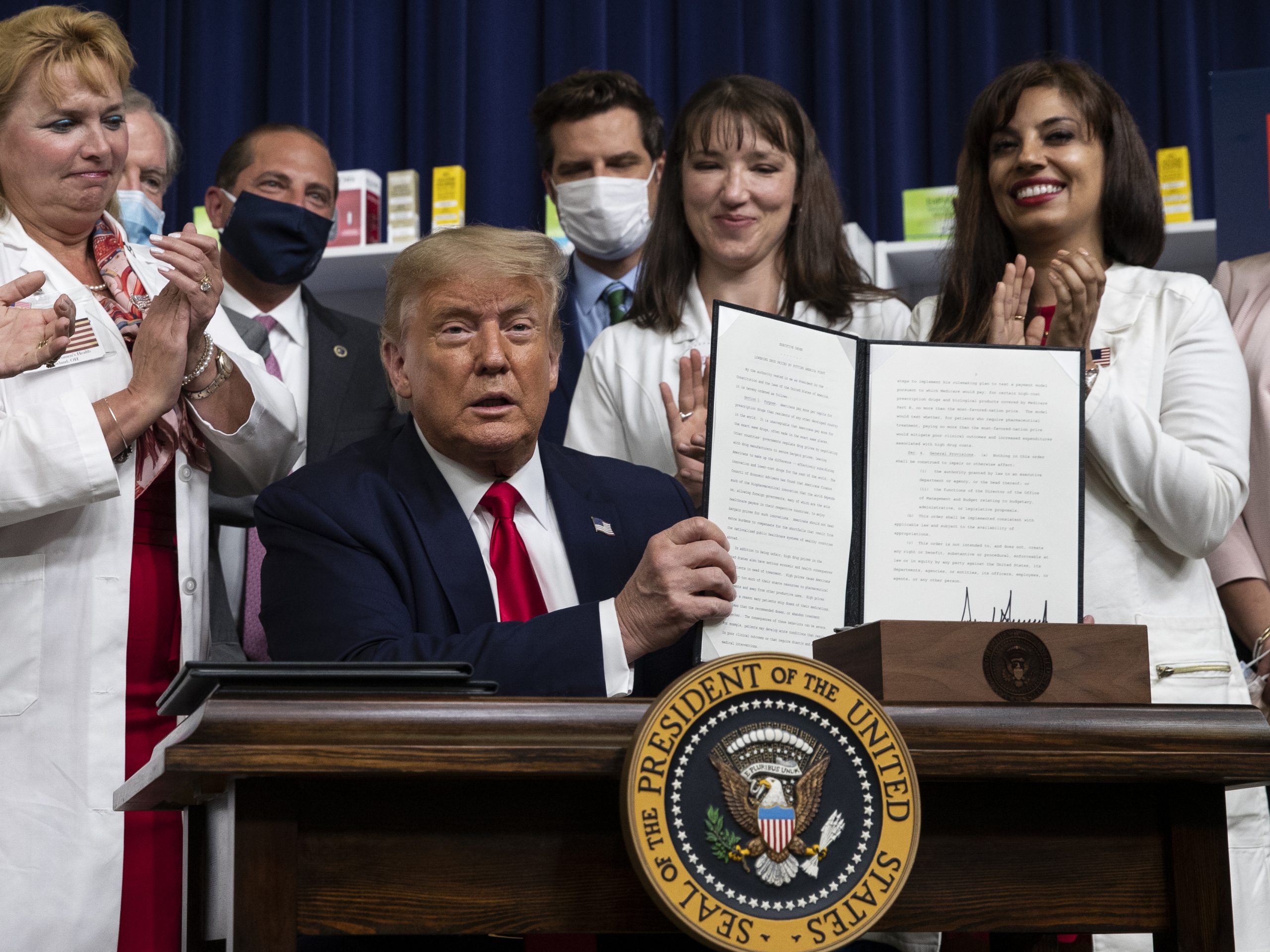

In 2016, President Trump made a campaign promise to bring down drug prices. For the past several years, Trump has advocated for using drug prices in other countries as a benchmark for Medicare prices. In July of this year, Trump signed an executive order that included his drug reference policy. He initially stalled on enforcing it, leveraging the policy in an attempt to gain concessions from the pharmaceutical industry. As these talks soured, Trump decided to move ahead.

On September 13th, President Trump scrapped the July order and issued a new executive order directing the Department of Health and Human Services to launch a demo of the policy. The underlying idea is captured by the “favored-nation” clause: for a given drug, Medicare will only pay the lowest price, adjusted for volume and GDP, offered to a comparable country.

Beyond this, most of the details are in the air. Trump has not specified which countries would be considered, although potential candidates include Canada, Japan, and a host of European countries. The order also leaves it open to the Secretary of the Department of Human Services, Alex Azar, to establish a payment model.

A litany of concerns has been brought up about the proposal. One worry is that the policy could simply induce cost-shifting, where companies recoup losses in one market by raising prices in another. Foreign countries face a collective action problem, where each sees strict price controls as in their own interest. If other countries aren’t willing to raise prices, drug companies may resort to raising prices in the United States’ private market. These downstream effects could not only hurt Americans with private insurance, but could also inadvertently raise prices for Medicare drugs not covered by the proposal, negating any cost savings.

Another potential problem is that any savings could come at the cost of pharmaceutical innovation. Researching a new drug is an expensive and lengthy process that costs over a billion dollars and takes an average of 12 years, all with a success rate of merely 10%. Unsurprising, studies seem to find that suppressing the drug company revenue could siphon funds from research and dampen the appetite for future investment, ultimately damaging the quality of healthcare.

A final worry is that the price of drugs in other countries may not be appropriate for Medicare. Companies such as Germany, Japan, and France use cost-effectiveness assessments to assign prices to drugs. However, countries conduct valuations with their own citizens in mind, which may not be suitable for Americans. For example, some commentators have suggested that valuation methodologies of countries like the UK and Canada tend to undervalue treatments for the elderly, chronically ill, and people with disabilities—not a great fit for Medicare.

One remedy for these shortfalls is to empower Medicare to directly negotiate prices. Instead of outsourcing negotiations to other countries, a government office dedicated to conducting cost-effectiveness assessments could help identify the proper cost of drugs for American consumers while encouraging the development of high-value drugs. This idea has also been introduced in Congress and enjoys high support from the public. For now, the question remains about whether Trump will successfully run his demo. However, a similar international drug pricing scheme was proposed by House Democrats last year. Moreover, candidate Joe Biden also seems to endorse the policy, suggesting “a reasonable price, based on the average price in other countries” for specialty drugs. Although the COVID-19 pandemic is currently capturing national attention, the soaring cost of drugs and solutions like international pricing promise to be subject of debate well beyond 2020.

Featured Image Source: Associated Press

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.