JUSTIN WANG – APRIL 12TH, 2023

The average price of a dozen eggs in the U.S. has jumped from $1.45 to $3.42 from February 2020 to present day – a 136% increase. Over the same timeframe, electricity services have exhibited a 25% hike, while rent has soared over 12%. With such marked price surges sweeping across all sectors of the American economy, inflation’s ominous grip has left no consumer or business unscathed. The threat of rising inflation in the U.S. undoubtedly preceded the recent pandemic, but it was amidst the turbulent macroeconomic setting of COVID-19 that it fully manifested in rapidity not seen in generations. While the scope of today’s upward inflationary spiral has had some smaller historical roots, its sharp rise and the alarming speed at which it has unfolded is astounding.

The onset of COVID-19, a pervasive modern pandemic, in conjunction with several accommodating governmental policies, has collaboratively and effectively stoked the flames of several underlying economic instabilities. The unique combination of several ongoing developments, including global supply chain disruptions, resource terrorism, the housing crisis, and widespread labor shortages, exacerbated an already vulnerable economic dynamic.

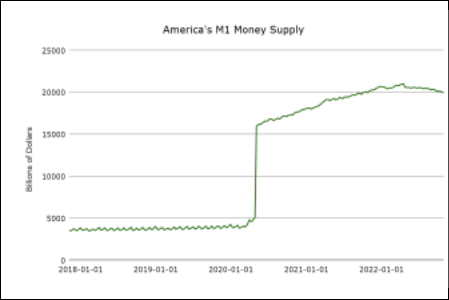

Unearthing the roots of the inflationary threat in the U.S. requires more detailed, time-lapsed analyses of all contributory elements, hierarchically ordering the most impactful one, if identifiable. The fiscal stimulus in March 2020, although necessary, set the nation into an incredibly diffuse demand shock: as consumers received thousands of dollars in federal stimulus funds, their purchasing power for COVID-related goods, combined with a fickle reaction to exclusivity for scarce items, yielded a widespread demand shock that emptied shelves and strained supply chains. Notably, in the month-long period between April and May 2020, America’s domestic money supply skyrocketed, with the M1 money supply, in particular, increasing four-fold from pre-pandemic levels.

This abnormal surge of the domestic money supply manifested in a domino effect as consumer demand, supply chain challenges, and pandemic regulations intersected. Steep increases in demand for both essential and discretionary purchases led to ill-equipped producers being unable to keep pace with market demands. Tax guidelines and inventory policies had been loosened in the months prior to COVID-19, which spilled over into supply chain bottlenecks when consumer demand soared. In light of the pandemic’s regulatory frameworks, difficulties relating to logistics and deliverables emerged, posing new obstacles that prevented manufacturers from bringing their products to market on a timely basis. Maritime shipping and airborne freight transport, two pillars of international trade, were faced with COVID-related disruptions that led to a slew of problems, including container shortages, port congestion, and route cancellations.

This pairing of abnormally high levels of demand with widespread supply chain issues has thus far prompted one of the worst inflationary episodes that the American economy has ever witnessed. In the absence of effective moderation from government intervention, upward pressure on consumer price levels and minimum wages will only increase further, sparking an even heftier wage-price spiral and initiating a bullwhip-like sequence of economic events that would only result in steeper increases in inflation. An extended period of inflated prices would only serve to further bruise segments of the population who have already been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic and its economic effects.

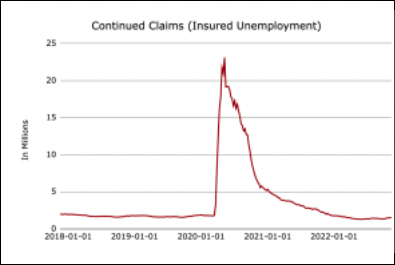

Essential workers, especially those employed in the food and retail industries, comprised a significant proportion of the U.S.’s unemployment claims during COVID-19. These workers have already exhibited large-scale exodus from the labor market – a marked result of the nation-wide lockdown procedures from Spring 2020. From March to May 2020, for instance, the U.S. Department of Labor noted a staggering twelve-fold increase in insured unemployment claims: in a matter of just two months, continued claims rose from roughly 1.8 million to over 23 million. Even the notable rate claim increases of historic economic downturns, including the 2008 recession and the dot-com bubble burst of 2000, pale in comparison to the scales seen in 2020.

Moreover, these lower-income consumers were intrinsically predisposed to suffer a greater impact from the effects of rising prices: the marginal propensity to consume amongst these liquidity-constrained consumers soared as inflationary impacts eroded their purchasing power. This impact is confirmed by the multiplier effect, which works in reverse when incomes stagnate while prices rise.

To address the worsening state of inflation in the American economy, proactive measures must be taken to tighten the nation’s money supply and cut unsustainable spending, regardless of the short-term economic consequences that may arise. The key to fighting long-term inflation lies in a comprehensive set of stringent fiscal and monetary policies; the Federal Reserve must turn towards unconventional tools, including quantitative tightening and interest rate hikes, while Congress needs to enact strict policies to disincentivize spending, whether it be from the government or from consumers. Utilization of these fiscal and monetary agendas would simultaneously normalize

The Federal Reserve’s balance sheet and deter spending, placing the economy in the ideal position for recovery from the grip of inflation.

Following the 2008 recession, central banks engaged in quantitative easing, or QE, in a coordinated effort to revitalize the global economy. A leading group of central banks, including those in the U.S., the U.K., the Eurozone, and Japan, commissioned large-scale purchases of mortgage-backed securities, two-to-ten year Treasury notes, and a variety of alternative assets to broaden national balance sheets and stimulate spending across all sectors. In the U.S., the Federal Reserve underwent three rounds of QE, spending over $2.5 trillion in doing so. These decisive injections of liquidity into the financial markets, both domestic and international, were able to largely serve their purpose of accelerating economic recovery following the 2008 market crash.

Amidst the current macroeconomic landscape, however, the converse must be accomplished. National balance sheets must be curtailed and spending must be checked to counteract the rapid growth of inflation. Quantitative tightening, or QT, must be collaboratively incorporated into the monetary policy agendas of the aforementioned financial institutions in an effort to reverse the tailwinds of the current inflationary crisis. Boldly, an extensive sale of assets from various central banks to the financial markets would successfully spark a sequence of decreasing asset prices, ultimately leading to less inflated costs being associated with consumption. In the U.S., QT would take on the form of a considerable release of the Federal Reserve’s excess fund accumulation, particularly through the sale of mortgage-backed securities, two-to-ten year Treasury notes, and alternative assets.

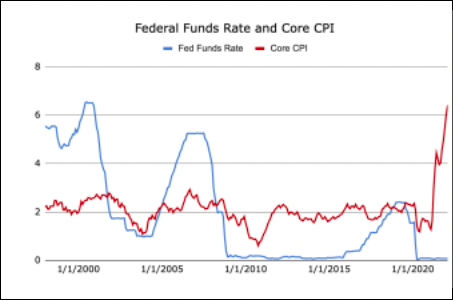

The incorporation of QT policies within the Federal Reserve System would also function as a means of increasing interest rates. As assets from the Federal Reserve flood the market, prices would fall, and upward pressures would be placed upon interest rates, effectively triggering noticeable increases. With continuous, heightened interest rates, consumers and corporations will veer away from both borrowing and spending at normal levels, causing a taper in inflationary growth. Here, interest rates and inflation have proven in holding an inverse relationship:

Monetary policy and inflation share a close, causal relationship with one another. Indeed, while central banks are well-equipped to confront inflation using these policies, supplementary assistance from fiscal policy administered by governments provides irrefutable, beneficial support. Following the 2008 financial crisis, governments scrambled to introduce a plethora of anti-recessionary fiscal policies. Many Keynesian procedures were implemented, including stimulative government deficit spending in the form of tax cuts and infrastructure investments. In the U.S., the Economic Stimulus Act of 2008 and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 were approved. Put together, these two acts endorsed $939 billion in government spending through tax rebates for lower-income consumers, tax incentives for corporations, and investments across multiple industries. Again, as was the case with QE following the 2008 recession, these fiscal policies proved successful, as their long-term benefits outweighed their upfront costs.

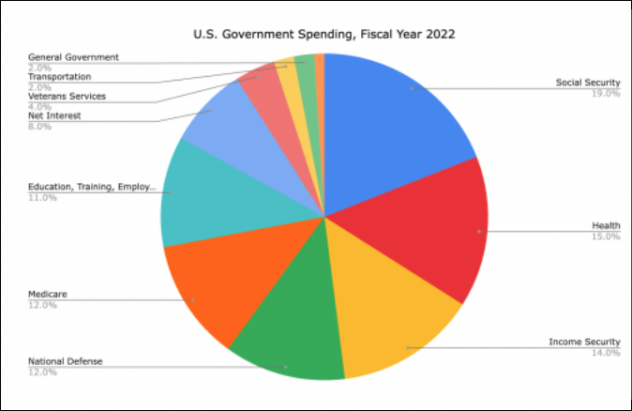

Governments must assume a proactive form of fiscal policy to facilitate economic recovery from the present-day threat of inflation. As opposed to inducing deficit spending, policymakers must produce legislation that ultimately bottlenecks spending, both from the government and from the consumer. Contrasting with the policies set in place in 2008 and 2009, the U.S. must raise tax revenues while cutting government spending. To account for the disproportionate economic impacts that the pandemic has already had upon lower-income consumers, tax revenues must be shifted towards targeting large corporations that benefited from the sustained market rally from April 2020 to December 2021. To cut government spending, legislators must push for lower costs within the

Healthcare industry to reduce Medicaid and Medicare related expenditures, which when combined, account for the largest proportion of government spending.

Given the deleterious economic impacts suffered since the onset of inflation, and understanding the possible implications of sustained price hikes on the American consumer, and indeed the broader economy, it is clear that a multifaceted policy agenda that utilizes both monetary and fiscal tools must be implemented. While it is still not too late, America’s policymakers must take initiative in sacrificing short-term satisfaction and political popularity in return for an escape from the grip of inflation, and ultimately, the establishment of long-term economic stability.

Works Cited:

[1] “2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.” Energy.gov,

https://www.energy.gov/oe/information-center/recovery-act.

[2] Andolfatto, David, and Li Li. “Quantitative Easing in Japan: Past and Present.” Economic Research – Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 1 Nov. 2014,

[3] “Categories of Essential Workers: Covid-19 Vaccination.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 29 Mar. 2021,

https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/categories-essential-workers.html.

[4] Censky, Annalyn. “QE2: Fed Pulls the Trigger.” CNNMoney, Cable News Network, 3 Nov. 2010, https://money.cnn.com/2010/11/03/news/economy/fed_decision/index.htm.

[5] Center for Preventative Action. “Conflict in Ukraine | Global Conflict Tracker.” Council on Foreign Relations, Council on Foreign Relations, 8 Nov. 2022, https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/conflict-ukraine.

[6] “Changes to Consumer Expenditures during the Covid-19 Pandemic.” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 3 May 2022,

https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2022/changes-to-consumer-expenditures-during-the-covid-19-pandemic.htm.

[7] Cho, Seung Jin, et al. “Covid-19 Employment Status Impacts on Food Sector Workers.” IZA, https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/13334/covid-19-employment-status-impacts-on-food-sector-workers.

[8] “Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: Rent of Primary Residence in U.S. City Average.” FRED, 10 Nov. 2022, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CUSR0000SEHA.

[9] “Consumer Price Index News Release – 2021 M12 Results.” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 12 Jan. 2022, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/cpi_01122022.htm.

[10] “Consumer Price Index News Release.” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 19 Jan. 2021, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/cpi_01132021.htm.

[11] “Consumer Price Index Summary – 2022 M10 Results.” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 10 Nov. 2022, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/cpi.nr0.htm.

[12] “Continued Claims (Insured Unemployment).” FRED, 1 Dec. 2022, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CCSA. 7

[13] “Covid-19 Economic Relief.” U.S. Department of the Treasury, 18 Oct. 2022,

https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/coronavirus.

[14] Duncan, Gary. “European Central Bank Opts for Quantitative Easing to Lift the Eurozone.” The Times, The Times, 2 Apr. 2010,

[15] Dworkin, David. “Two Issues Define America’s New Housing Crisis.” National Housing Conference, 25 Oct. 2019, https://nhc.org/two-issues-define-americas-new-housing-crisis/.

[16] “Economic Impact Payments.” U.S. Department of the Treasury, 17 June 2021,

[17] “Federal Funds Effective Rate.” FRED, 1 Nov. 2022, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/FEDFUNDS.

[18] “Federal Reserve Announces It Will Initiate a Program to Purchase the Direct Obligations of Housing-Related Government-Sponsored Enterprises and Mortgage-Backed Securities Backed by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae.” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System,

https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/monetary20081125b.htm.

[19] “Federal Reserve Issues FOMC Statement.” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 24 Oct. 2012, https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/monetary20121024a.htm.

[20] “Fiscal Data Explains Federal Spending.” Federal Spending | U.S. Treasury Fiscal Data, https://fiscaldata.treasury.gov/americas-finance-guide/federal-spending/.

[21] H.R.5140 – Economic Stimulus Act of 2008 – Congress.

https://www.congress.gov/bill/110th-congress/house-bill/5140.

[22] Helper, Susan, and Evan Soltas. “Why the Pandemic Has Disrupted Supply Chains.” The White House, The United States Government, 30 Nov. 2021,

[23] J.P. Morgan Chase. “What’s behind the Global Supply Chain Crisis?” J.P. Morgan, J.P. Morgan Chase, 25 May 2022, https://www.jpmorgan.com/insights/research/global-supply-chain-issues.

[24] Jones, Kathy. “Rate Hikes, Quantitative Tightening, and Bond Yields.” Schwab Brokerage, 13 Sept. 2022, https://www.schwab.com/learn/story/rate-hikes-quantitative-tightening-and-bond-yields. 8

[25] Luscombe, Richard. “Covid Caused Huge Shortages in US Labor Market, Study Shows.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 13 Sept. 2022,

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2022/sep/13/us-labor-shortage-long-covid.

[26] Lutz, Jamie, and Caitlin Welsh. “High Prices, Empty Shelves.” High Prices, Empty Shelves | Center for Strategic and International Studies, 1 June 2022, https://www.csis.org/analysis/high-prices-empty-shelves.

[27] “M1.” FRED, 22 Nov. 2022, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/WM1NS.

[28] Oricha Ali, Abdulmalik. “Quantitative Monetary Easing – the History and Impacts on Financial Markets.” Academia.edu, 24 May 2014, https://www.academia.edu/6943181.

[29] Paulson, Mariko. “Background: Marginal Propensities to Consume in the 2021 Economy.” Penn Wharton Budget Model, Penn Wharton Budget Model, 3 Feb. 2021,

https://budgetmodel.wharton.upenn.edu/issues/2021/2/3/background-mpc-in-2021-economy.

[30] “Quantitative Easing.” Bank of England,

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy/quantitative-easing.

[31] “Sticky Price Consumer Price Index Less Food and Energy.” FRED, 10 Nov. 2022, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CORESTICKM159SFRBATL.

[32] Stone, Chad. “3 Reasons Why Inflation Fears Shouldn’t Block a Well-Designed Economic Package.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 5 May 2022,

[33] Williamson, Stephen D. “Quantitative Easing: How Well Does This Tool Work?: St. Louis Fed.” Saint Louis Fed Eagle, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 9 Dec. 2021,

[34] Winck, Ben. “The Stock Market’s Rally through 2021 Blew Wall Street’s Forecasts out of the Water.” Business Insider, Business Insider, 31 Dec. 2021,

[35] Zahn, Max. “Inflation Hits These Products the Most and These the Least: EXPLAINER.” ABC News, ABC News Network, 10 Aug. 2022,

https://abcnews.go.com/Business/inflation-hits-products-explainer/story?id=88192701. 9

[36] Zumbrun, Joshua. “Fed Undertakes QE3 with $40 Billion Monthly MBS Purchases.” Bloomberg.com, Bloomberg, 13 Sept. 2012,

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.