DHOHA BARECHE – November 1, 2022

EDITOR: Katherine McKernan

Introduction

Following WWII, there was a great sense of optimism regarding development, globalization and the role of education in facilitating these advancements. In 1983, U.S. President Ronald Reagan published a report titled “A Nation At Risk: The Imperative of Education Reform” blaming the education system for why other countries were advancing past the U.S. in commerce, industry, science and technology. Economic advancement didn’t solely rely on acquiring physical capital, but cultivating human capital. He argued, “learning is the indispensable investment required for success in the information age we are entering.”

The 1980’s ushered in a new era for American higher education that linked it to international corporatization. It marked the inauguration of neoliberalism that brought about market reforms to every aspect of society and succumbed the education system to the needs of the market. According to political theorist Wendy Brown, neoliberal rationality unleashed destruction upon higher education and changed the way we view it. Rather than pursuing an education for one’s own edification, social and market pressures have enslaved people to industry demands and allowed them to disregard the value of learning.

Not only has neoliberal reform transformed the way individuals value education, but it has also changed the way universities operate. First, unemployment, poverty and inequality were seen as a failure of the education system rather than a structural capitalist problem. Second, it placed a great emphasis on educational advancement yet decreased funding for it, leading to high tuition increases and the reliance of universities on private fundraising. Third, universities became subjected to market pressures by prioritizing research with commercial applications.

The Mismatch Discourse and Human Capital Theory

The mismatch discourse emerged in the 1950s and blamed the education system for not meeting the needs of the market, according to professor of international education policy Steven Klees. In other words, education was not teaching what the economy needs and unemployment was to be blamed on schools for not preparing a skilled workforce that met corporate demands.

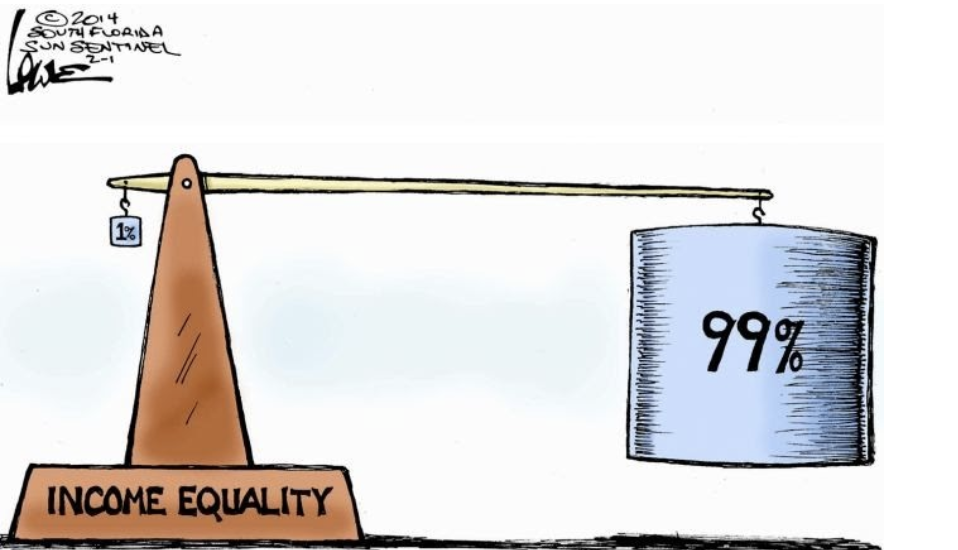

Underlying the mismatch discourse, he argues, is human capital theory. Coined by American economists Gary Becker and Theodore Shultz in the 1960s, human capital theory is the idea that education increases one’s productivity and skill set. Klees argues that human capital theory took out sociology from labor economics and commodified it into something based on supply (education) and demand (jobs). However, he said greater emphasis was placed on individuals to cultivate employable skills rather than creating jobs that required valuable skills. Thus, the burden of employment falls on the individual and education system rather than the market. The triple challenge of poverty, unemployment and inequality were seen as dependent on individual skills and how well the education system prepared future employees.

But underlying both human capital theory and the mismatch discourse is neoliberal reform. Klees writes that neoliberalism is more than just an economic system but has political, social, and cultural ramifications. It’s a system that advocates for decreased government spending and privatization of public services. The objective of neoliberal reform in education, Kleez writes, is to cut spending. This was reflected in decreased teacher salaries and educational resources since the 1980s. Although production of human capital is the role of the education system in a capitalist society because it is dependent on labor, neoliberal reform is contradictory in its realization of this goal as it has decreased funding for public higher education and made it more inaccessible to the lower classes.

At UC Berkeley, for example, state funding has been decreasing on a per student basis for the past 20 years while enrollment has increased from 32,000 in 2000 to 43,000 today. As the UC system tries to meet the state’s goal of expanding higher education to promote social mobility, university resources are struggling to meet the demand of existing students.

But this isn’t just a phenomena unique to a large public research university like UC Berkeley. From 1991-2008, there has been a stagnation in public support of higher education as student enrollment continued to grow at a faster rate than public funding. According to a 2019 report by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, public higher education has seen significant cuts since the Great Recession that has led to increased tuition costs and limited course offerings, resulting in greater inaccessibility for low income and marginalized students.

Although a Pew Research study based on a 2019 Survey of Household Economics and Decision Making found that adults with a bachelor’s degree earn more than those who don’t, first generation graduates still lag behind others. The study shows that the educational attainment of one’s parents affects their likelihood of completing a degree and impacts future earnings.

Since first generation college students are more likely to incur student debt than those with college educated parents, households headed by first generation graduates earn lower ($152,000) than households headed by a second generation college graduate ($244,500).

But since there is great pressure on students to develop the skills and knowledge necessary for tomorrow’s jobs, incurring student debt for the purpose of an education is justified under the assumption that they would be able to pay it off with their future salaries.

In 2019, the Federal Reserve found that student debt increased by 107% this decade. In 2009, American student debt was around $772 billion dollars but at the end of 2019 it increased to $1.7 trillion dollars. Not only has higher education become inaccessible, but people no longer see the value of a college degree due to rising costs.

Besides the contradictory goals of neoliberalism that recognized the importance of human capital yet decreased the funding to enhance it, another major effect of neoliberalism on higher education is how we no longer value it as a tool of personal growth but rather measure it in economic terms.

“The End of Educated Democracy”

Besides privatization of public goods and skyrocketing tuition costs, what’s more at stake, Brown argues, is the loss of an educated citizenry. From the interwar period up until the 1960s, a great emphasis was placed on a liberal arts education because of its holistic approach to knowledge and the importance of cultivating a well-rounded, free individual. A college degree wasn’t solely valued because it promised social and upward mobility, but because of the knowledge and intellectual skills it granted.

But now the status of a liberal arts degree is eroding from all sides. In the End of Educated Democracy, Brown writes, “Cultural values spurn it, capital is not interested in it, debt burdened families anxious about the future do not demand it, and neoliberal rationality does not index it.”

As a result, humans are solely viewed as market actors that can be understood “in the financial language of speculation, leveraging and risk-taking” as opposed to sovereign individuals. One’s worth is defined by the value of their labor rather than their intellect or character. Neoliberal market reforms in higher education have pushed universities and college students to prioritize technical and practical degrees over intellectual development.

Academic Capitalism

Academic capitalism is a theory that explains how the university system has transformed in response to external pressures such as market demands and funding cuts. The global economy has made knowledge a valuable asset that universities buy and sell in the market, according to associate professor of higher education Wilmington Kevin R. McClure.

Academic capitalism takes shape in the university system in different ways. As a result of declining funding, faculty are pressured to apply for more grants, seek funding for research projects with market applications, and attract students by teaching more practical courses.

Additionally, there’s been a massive decline in tenure-track positions as universities continue to replace them with adjunct faculty. One of the reasons for this, McClure says, is that adjunct faculty are a low-risk investment. If the university, for example, wants to experiment with a project or program and it doesn’t work out, they would much rather hire an adjunct professor to teach it due to the flexibility of letting them go in case it doesn’t work. While tenure faculty are tasked with doing important research for the university’s revenue-generating programs that will increase its prestige and student enrollment, adjunct professors and part-time faculty are tasked with teaching the majority of other courses so tenure faculty can focus on research.

As a result of decreased public funding over the years, universities have had to reexamine their priorities. In Unmaking the Public University, Christopher Newfield argues that universities have become increasingly reliant on private funding, and as a result, resources are allocated toward programs that meet market demands in science and technology. Furthermore, this dependence on private funding “fed the tendency to judge higher education less by its overall contribution to all the forms of development–personal, cultural, social and economic–than by its ability to deliver new technology and plug in workforce to regional businesses.”

This can be reflected in the types of degree awarded. Between 2009-2020, business was the most popular degree nationwide. At UC Berkeley, however, computer science has been the top degree since 2019. Before that, economics had the largest number of undergraduate degree recipients from 2014-2018.

Conclusion:

Brown writes, “Human life wholly bound to the production of wealth, whether laboring to produce it or hovering over its accumulation, is small and unrealized.”

While an industry-influenced education is necessary to prepare students for the workforce, it should not be the sole function of a university. The education system should develop both the politically and socially aware citizen and job holder. According to Brown, the U.S. in the postwar era reflected a commitment to a liberal arts education that emphasized the holistic development of the citizen and worker as well as made it more accessible to historically marginalized groups. A liberal arts education used to be only accessible to the elites then it shifted to being afforded to people of color and lower income individuals and now its status has completely eroded in favor of technical and practical forms of knowledge, according to Brown. The underlying issue with neoliberal reform in American higher education after World II is its regard of the human subject as a form of capital to be exploited by the market. Not only is it dehumanizing in that it disregards the importance of developing a well rounded ethical individual with a wide variety of skills and traits, but it decreased funding for higher education and placed the burden upon the individual and university.

Even in today’s technologically advanced society, industry does not solely seek individuals with technical skills but looks for well rounded employees with a wide variety of skills such as empathetic listening, communication, creativity and critical thinking.

As the disconnect between employers and employees continues to widen with the rising trend of “quiet quitting,” it becomes increasingly important for the public higher education to rethink its model and for students to reevaluate their educational and career goals.

Featured Image Source: Minute

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.