ANASTASIA PYRINIS – NOVEMBER 20TH, 2017

There is a widespread social understanding that corporations are evil. They are portrayed as all-consuming giants that prey upon the everyday worker. In media, an entire dystopian film franchise can be built around a doomsday scenario where a corporation gains complete control and obliterates any concept of freedom or democracy. Yet, while it may be true that corporations often forgo their social responsibility since “there is one and only one social responsibility of a business” – to make money – as stated by Milton Friedman in Capitalism and Freedom, it is that self-interest that drives the economy just as much as individual concern for self-interest drives the desire to work.

So, when fiscal conservatives propose plans to decrease corporate taxation, fiscal liberals, without fail, rise in uproar. They remind everyone of all the evils of corporations – about their greed and their ever-accumulating wealth. But the truth of the matter is that the opposite scenario, raising taxes on corporations, does not do anyone favors.

There are several reasons why it is far more prudent to cut corporate taxes rather than raise them. For the purposes of this article, however, just one of those benefits will be explored: quite simply, a comparatively lower corporate tax rate allows the United States to retain and attract corporate investment and headquartering in the United States.

A lower corporate tax in a country neighboring the US can prompt a business with the requisite means to move its headquarters to the country with the lower corporate tax. Nothing would change for the company except its tax rate. But this would hurt the American federal government, for its tax policy would essentially sacrifice billions of dollars in revenue when it could have instead lowered the corporate tax and kept a majority of those dollars.

For example, in 2014, Burger King moved its corporate headquarters to Canada, despite being an American company, in an effort to evade the higher corporate income taxes in the United States. Canada has a corporate tax rate of 27% while the United States, which has maintained its corporate tax rate since 1909 (with few fluctuations), has a 35% tax rate.

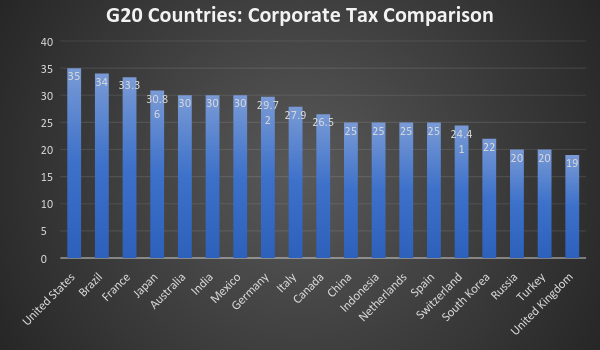

To further mark the obsolescence of America’s corporate tax rate, in comparison to other G20 countries, the United States tops the list with the highest corporate tax rate–far exceeding competitors like the United Kingdom, which has a corporate tax rate of 19%. In fact, when comparing the United States with the corporate tax rates of countries around the world, it ranks among Gabon, Congo, Chad, and Zambia, all of which also have a 35% corporate tax rate. Meanwhile, progressive countries like Sweden, Switzerland, and Norway have corporate tax rates of 22%, 24.41% and 24% respectively.

Figure 1: G20 Corporate Tax Comparison (Data Obtained From Trading Economics)

But what does this staggering difference mean? For one, it indicates that corporate tax reform is necessary for America to remain competitive in keeping corporations headquartered in the United States as well as encouraging relocation to the United States. While decreasing corporate taxes will garner less federal revenue from individual companies initially, it will prompt future gains through company retention and an appeal to new companies moving to the United States.

Under the new Republican tax bill proposal, that corporate tax will be dropped to 20%. This staggering drop will then place the United States only second to the United Kingdom among the G20 in terms of corporate economic tax, a drop that will ensure domestic corporate retention in addition to attracting the headquarters of corporations around the world.

Why is this competitiveness important? Quite simply, it allows the United States to be a flourishing center of economic growth. As reported by the National Bureau of Economic Research, “tax cuts are an effective way to bolster a weak economy and create jobs.” While the research notes that tax cuts for the top 10% have little to no effect on the economy, it does not consider corporations to be a part of those 10%. Rather, corporations are considered as an employment means that, for the most part, employ low and middle class individuals, not the top 10%. Coupled with what the Harvard Business Review describes as a “strategic intent” to expand whenever possible, corporations will not spend surpluses from lower tax rates just to raise CEO salaries but rather use that surplus to expand the company. That corporate expansion, by its very definition will create more jobs. Thus, as more companies base their operations in the United States, more job opportunities will surely come, and American economic influence will increase.